So little land left, so much pressure to build…. That combination is becoming more stressful in the places I work and live. But even if not common in your area, perhaps this primer on zoning will still be helpful.

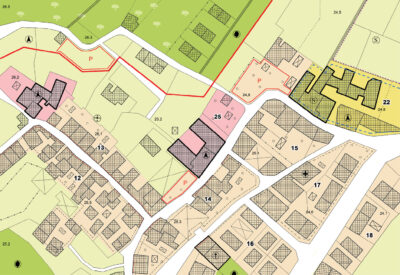

First on the agenda is to define zoning. The concept is to divide a municipality into different structural and usage areas by means of local regulations and ordinances. The resulting array of basic zoning districts (generally for residential, commercial, industrial/manufacturing, or mixed use) is subject to further categorization within each type of district to specify building bulk, density, and specific uses. We see different types of allowable buildings, limits on building heights and footprints, allowable proximity to property lines, minimum lot sizes, permissible signage, and other variations within various zoning district types.

Why have zoning? The intent of regulating land use is to provide a value to landowners by balancing different land uses, creating a place that people want to live and work while adding stability to land values. Presumably zoning follows a comprehensive or master plan, which is meant to achieve a balance of social, economic, and physical factors in the area’s development.

Some communities may apply an overlay zone to a previously identified base zone to add rules or make existing regulations stricter. Overlays are often employed to protect special features such as historic buildings, wetlands, steep slopes, and waterfronts, but they can also be used to promote specific development projects. While overlay zoning can help communities meet specific goals, it can also complicate approval and development processes, making them longer and more expensive.

Spot zoning changes the zoning of a specific piece of property in an otherwise designated land use zone. Areas are singled out to be treated differently from other parcels in the immediate area in the same zone, and the change is inconsistent with the municipality’s general comprehensive plan. Those general plans are made to enhance the health, safety, and general welfare of the community, while spot zoning often enhances only the pocket of the landowner receiving this special alteration of the land use regulations.

When a development proposal strictly meets zoning and building codes, it doesn’t need any special or discretionary approvals to proceed. This is “by-right” development, sometimes called “as-of-right” development. The benefit of by-right development for residents is the predictability and certainty about what kind of development can be expected in a neighborhood. The benefit to those planning to develop their land is knowing what hurdles they can expect to encounter on the way to project completion. This means that the overall road to project completion will be shorter and less expensive when no discretionary approvals are needed: no time before public boards. Difficulties arise within communities when something that meets the letter of ordinances doesn’t meet the spirit of those land use regulations. Proposals may be out of scale or inappropriate for a neighborhood, but it is difficult to defeat “by right” development.

There is a difference between non-conformance and non-compliance. Land use that was in line with zoning at the time of development (if there was any zoning in place at the time) may not be aligned with current zoning. This is a non-conforming use that is generally grandfathered for as long as the use is continued, but that specific non-conforming use can’t be changed to a different non-conforming use. In contrast, new non-compliant development proposals don’t meet the zoning requirements currently in place.

Most older and historic buildings would not be legal if having to meet current zoning codes. Attempting to reuse older structures means that changes in the original purpose of the structures (likely pre-zoning) will encounter many new and sometimes difficult requirements to meet. One resolution may be to alter a community’s zoning code by upzoning. This expands the capacity for new or re-development by adjusting the permissible building envelope, or allowable physical extent of a structure on a lot. This can be accomplished by changing allowable building heights or the density of development.

Another option is to apply for variances from zoning codes. In the process of applying for proposal approval, some waivers from strict compliance might be easily acquired, but will often require notice to and written acceptance by property owners within a regulatorily prescribed distance of the proposed development. Variances are meant to provide relief from strict compliance with zoning regulations where it would cause practical difficulty or unnecessary hardship for the landowner. Variances typically are only available for exceptions to physical regulations (such as setback requirements) and not to uses, although some jurisdictions may allow use variances.

The last option is to appeal the decision of a denied development approval. This is best done with legal assistance, as both zoning rules and the nature of zoning boards are complex. Hearings before zoning boards can include sworn testimony by witnesses, and board decisions can be further appealed to the court system.