I am asked more often than I’d like about how far back to research deeds in the process of surveying. My answer is along the lines of “It depends upon your tolerance of professional pain.” What I mean by that is, just like searching in the field, searching records of property location and configuration is a process dictated by what each individual feels answers all questions adequately, serving the client while protecting against liability from oversight or negligence. My view is that we can pay now in sweat equity over the work, or we can pay later in nervous sweat over possible licensure loss or litigation.

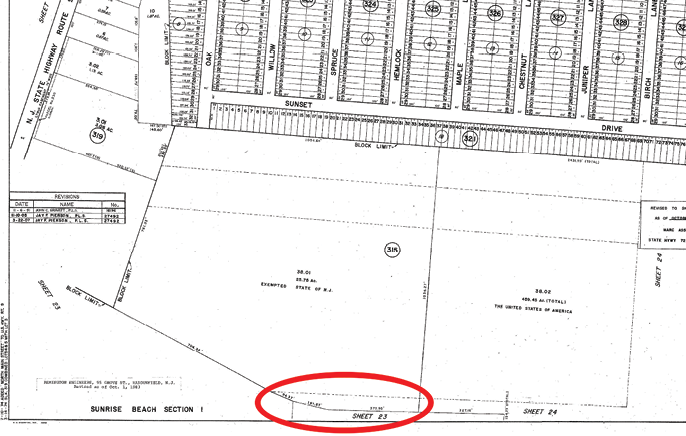

The title company reported the circled area on the tax map as a deed gap out of the subdivided Lot 38, misconstruing the dashed lines and compounding a title searching error.

When I’m called to help in suits about defending someone’s property rights, my research isn’t necessarily limited to deeds in the county clerk’s office. Sometimes I’m deep into old maps to find references to old town or road names, or books on local histories to find family members for help in tracing title references. The following are examples why research in general is important, and why, although vital, deeds aren’t always the only resource to rely upon.

The owners of a landlocked parcel sued for access across land owned by the people I worked with, based upon an implied right of access. The plaintiffs had bought seven wooded acres for $5000 and specific language in their deed that no access was provided or guaranteed. That should have been enough to put them on notice that there were problems with their development plans. But their claim of implied rights to cross the defendant’s land were shaky. Basically, it boiled down to wanting the shortest route to a public road.

Landlocked owners certainly have a right by claims of necessity to access their land, but the location of that access can only be by implication under certain circumstances. The first factor in implied easement location is that the landlocked tract was divided out of the tract over which it now wants access to a public road. The grantor has a responsibility to allow the grantee access to enjoy the newly acquired land. The plaintiffs did research deeds back to the creation of their landlocked tract in 1825, but they didn’t research any abutting lands to see if there was common ownership.

My research showed that the plaintiffs’ chain of title and the defendant’s chain of title had never intersected in common ownership, especially not at the critical point when the landlocked tract was formed. I unearthed old family records to trace who was related to whom (by birth or marriage) and when. I also located old maps showing that access to the currently landlocked parcel had been in a different direction, not over the defendant’s land (which would have been trespassing if not by permission). The plaintiffs could negotiate for an easement over the defendant’s land, but there was no implied access right that should be granted free of charge.

In a much shorter disagreement with a title company, they had listed a strip of land shown on the tax map as excluded from the proposed title insurance policy. The title commitment listed only three deeds as the basis for title for the State of New Jersey’s ownership of the lot in question, and none of them covered the skinny piece at the southerly edge of the tax map lot. Yes, we all know the faults of tax maps, but in this instance, I looked at the cited deeds and found that they correlated to other dashed lines crossing original Lot 38, which had been divided into Lots 38.01 and 38.02 (see the illustration). It can be onerous to search the grantor/grantee indices to trace the title of the State of New Jersey or the United States of America (the parcels involved here). But the State did have some survey plans showing the division of Lot 38 from a larger tract to the east, and that plan listed a number of deed references.

Thank goodness for plan notes! Thank you for documenting the source of your conclusions! Securing those deeds, I found that the circled area on the tax map shared herein was part of a longer “finger” of land that was in a deed comprising part of the larger tract to the east of then-Lot 38.

The title officer I dealt with had originally concluded that the skinny “finger” on the tax map represented a deed gap, until I pointed to the other dashed lines crossing Lots 38.01 and 38.02. Those lines conformed to the lines of the deeds he had cited in the title report; deed plots convinced him of my argument. After reading the deed I cited as the source of title for the “missing” area, he admitted that it had been missed because it was originally part of a different (and unsearched) lot.