Most days, Ellen Zieleman and her guide dog, Sjef, make their rounds in Nijverdal, a village of 22,000 people in the Netherlands. A stroll to call on friends, pick up groceries, or board a train to visit three grandchildren an hour away are things Ellen has only recently decided to do on her own.

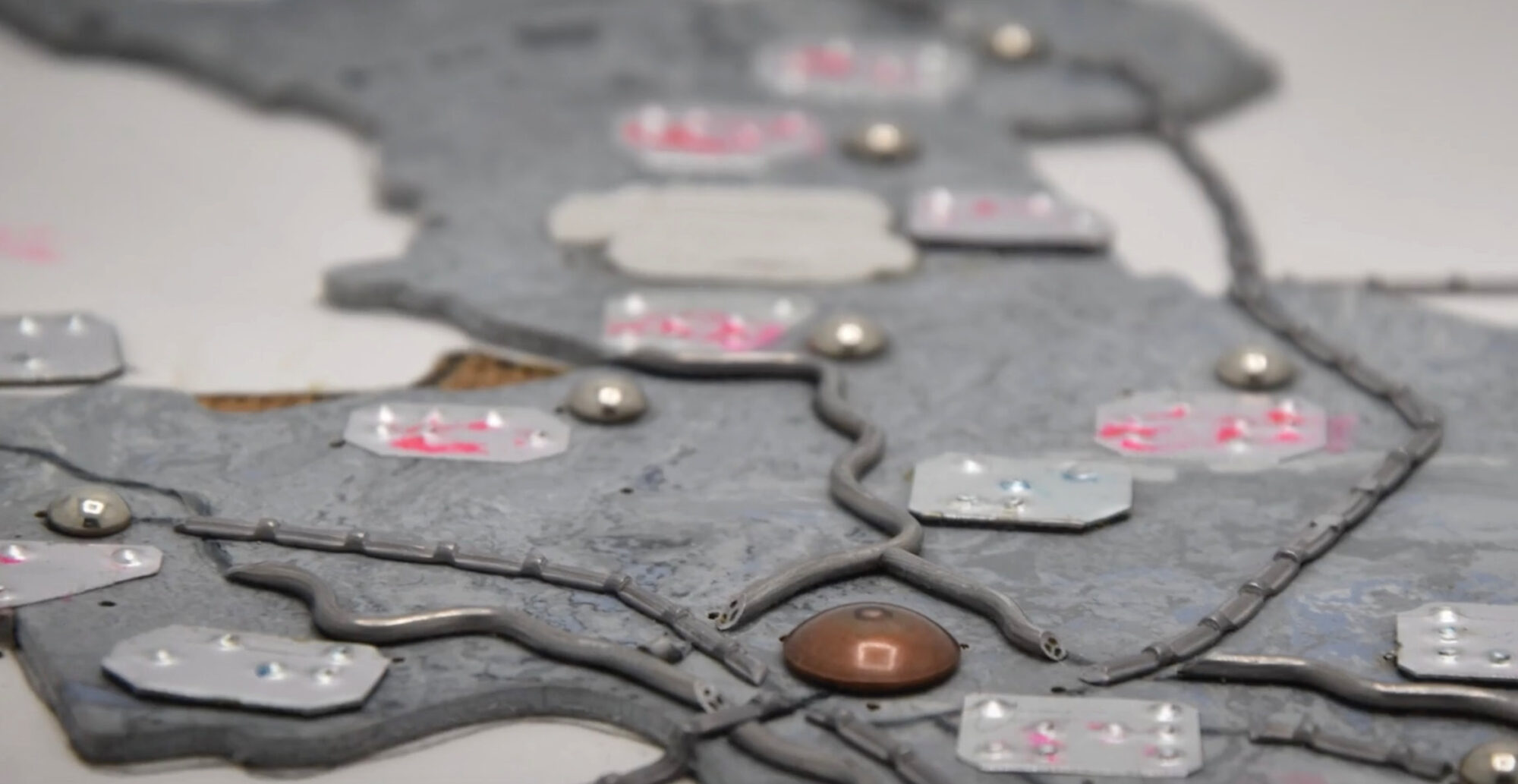

For over 200 years, tactile maps have been created using materials like wood, wire, and nails.

For Ellen, 60, tactile maps give her the confidence and additional guidance she needs to travel unassisted after losing her eyesight fully five years ago.

Tactile maps are printed in a way that raises the lines and symbols on an otherwise flat page. Ellen uses her fingers to locate streets, bus stops, and buildings, similar to how someone reads Braille. With these maps, she can orient herself to a new environment or identify shortcuts. She and the mapmakers believe access to tactile maps could help improve mobility and expand opportunities for many of the 2.2 billion people living with blindness or some type of vision impairment globally.

Yet, for many, it would feel unsafe to venture as far from home unassisted as Ellen has. Too often, they wait until someone can travel with them. Those who become shut in and afraid, as Ellen once was, are part of the reason she pushed herself to regain independence after congenital cataracts diminished her ability to see and, ultimately, left her blind.

Each time Ellen travels alone, she believes she is changing perceptions of what is possible for herself and others. To be clear, she is working to change expectations among those who have sight as well as those living with impaired vision or blindness.

“I would like the whole world to know that when someone is blind, someone is not otherwise impaired,” Ellen said. “I can think clearly. I can do everything, only I cannot see.”

The Health Impacts of Tactile Maps

Loneliness has become a social epidemic, especially for people living with disabilities. More than 7 million Americans have impaired vision or blindness and 93 million more are at risk for severe vision loss, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As the US population ages, even more people will face loss of sight and the declines in physical and mental health linked to it, the CDC reported. Impaired vision and blindness make falls, social isolation, depression, anxiety, and fear more common.

Today, tactile maps are digitally designed, and then printed on special paper with raised ink.

Globally, vision impairments are responsible for lost productivity estimated at $411 billion per year, according to the World Health Organization.

Ellen, who now has artificial eyes, experienced a decline in her own sense of well-being as cataracts turned her lenses cloudy and opaque. She said she still grieves the loss of one eye in 2017 and the other in 2018.

Although she had lived with impaired vision since birth, blindness was more vile. Along with her independence, it stole the beauty she saw in flowers, trees, birds, and the smiles of her grandchildren.

Desperate to reconnect with the world outside of her home, Ellen searched for aids and technology that could help. During her search, she found an opportunity to become a volunteer tester and, soon after, an expert user of tactile maps.

Four organizations are working together to develop technology to produce these maps. Ellen and 30 other testers are helping the project’s researchers evaluate map features and designs. For instance, each map’s markings and symbols must be easy to read and distinctive from other features by touch.

Even at this stage of development, the maps bring a neighborhood’s streets, buildings, and public transit into view in Ellen’s mind. She studies the maps at home before a trip and uses a voice recorder to make notes about landmarks along her route. Afterward, she can use the landmarks to retrace her steps. She can determine proximity between one destination and the next, and she can distinguish between footpaths and pedestrian-friendly streets.

“Ellen has been on this journey with us from the beginning,” said Jolijn Jansen, a research specialist with Foundation Accessibility, one of the organizations developing the maps. “She is one of our most loyal experience experts because she is very motivated to help improve our maps.”

Ellen and her golden retriever have visited schools and universities to talk about her life experiences. She describes having to learn new ways to accomplish everyday tasks. She also speaks about the need to open up society more broadly to people who have disabilities.

“I want to use my talents, my brains, and my speaking to help people,” she said. “I would like for them to use all the possible tools to improve their lives. I cannot make their eyes better, but I can help them find the right tools to use to be as free as I am.”

The Challenges of Making the World Map Accessible

Ellen’s volunteer work as a product tester is expected to help the developers deliver a new generation of tactile maps. Planning began in 2022 between Kadaster, the Netherlands’ national mapping and land registry organization, and Foundation Accessibility, which advises businesses on digital, physical, and social accessibility.

Nonprofit Dedicon Foundation, a maker of tactile maps and the largest producer of alternative reading formats in the Netherlands, joined the effort in March 2023.

The fourth partner, the Netherlands operation for California-based technology maker Esri, joined the same month. Esri is the premier producer of geographic information system (GIS) technology. Its products are used globally in government and business for digital mapping and location-based analysis, typically for efficiency in operations and logistics.

The partners’ vision for an efficient, affordable, user-friendly system for production and distribution of tactile maps could have many indirect benefits. This includes enriching their customers’ understanding of geography and world events. The project also could open up a largely untapped global consumer market for geospatial data and services.

“We believe geographic information should be available to everyone,” said Vincent van Altena, senior consultant, research and innovation, at Kadaster. “We want visually challenged people to be able to access that information.”

Scaling up production of tactile maps will take time. It will require moving from hand-drawing maps to more efficient processes that make use of technology and automation. A second requirement will be to develop designs that are simple enough to be readable but still accurate enough to provide a useful level of detail.

“Development of an accessible, user-friendly tactile map is notoriously difficult because [people living with impaired vision] process spatial information differently, and touch is less sensitive than sight,” said Jolijn Jansen, a research specialist with Foundation Accessibility. “Therefore, tactile maps cannot be inferred directly from current graphic maps.”

Technology Supports Access and Inclusivity

Dedicon Foundation’s tactile maps traditionally offer a view of a neighborhood, city, or country. A cartographer or illustrator draws provinces and capital cities, and sometimes primary and secondary roads, footpaths, bicycle routes, or other features upon request. Titles and other text are presented in Braille.

To distinguish among a map’s many features, the designers include various styles and patterns of shapes, lines, and dots. These help the reader identify elements such as buildings, water, and parks.

The time required to produce each map manually has limited production and availability of tactile maps. Drawing on existing global topographic data could quicken production times. For example, Esri’s ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World includes already-digitized maps that are available at varying scales and in multiple formats and configurations. By referencing existing libraries, the development team hopes that usable maps one day can be completed in minutes rather than in days to weeks.

Eventually, those who request maps might also ask for complimentary pages that show amenities such as restaurants, public transportation, or retail stores. Building separate pages is necessary to prevent crowding that can make these maps harder to read.

The prototypes are printed onto swell paper, which has a special coating. Passing the printed page through a heating device causes the ink to rise and become detectable to the touch.

Ultimately, the development team would like to make the maps available through a self-service online ordering system, with options for customization. For the Dutch market, people who have impaired vision or blindness might one day get access to maps with a 33-euro annual membership to the Library for Adapted Reading.

Freedom at Her Fingertips

Learning to read tactile maps takes time and practice. In return for time invested, Ellen has learned to recognize not just the locations of pedestrian routes but how different neighborhoods and cities are laid out.

Because of the maps, Ellen now understands where she lives in relation to other places. With one finger, she has explored the Netherlands. She needed both hands to trace Russia’s borders.

“My world view has been enriched,” Ellen said in a video interview. “I now have the same access to knowledge that other people have. I’m much better prepared and feel more confident when finding my way.”

Sophia Garcia is Esri’s industry solutions specialist for equity and civic nonprofit organizations. In her previous work at the Dolores Huerta Foundation and as a consultant, she collaborated with community organizations and local governments across California to enact equitable redistricting and champion community GIS.