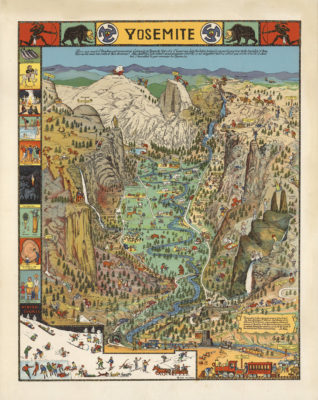

Yosemite, bird’s-eye view map by Jo Mora. 1931 original was blackline, with color version issued in 1941. Mora’s hand-colored original is at the Yosemite Museum. David Rumsey Map Collection

Pass between stone sphinxes and cross the sunlit space beneath the muraled rotunda of the Los Angeles Central Library and you’ll arrive at a temporary art exhibition, Jo Mora: Mapmaker of the American West. On display is an intimate collection of maps and bird’s-eye views drawn between 1926 and 1945, together with other works by Jo Mora. The exhibition is an opportunity to appreciate an American artist who, among the many mediums and forms he worked in, advanced a style of engaging pictorial maps that burst with color and whimsy.

Fans of the ’60s folk-rock band the Byrds will recognize Mora’s art from the album cover for Sweetheart of the Rodeo. As a creator of public art, Mora sculpted friezes for California’s Monterey Courthouse and a monument to the Spanish novelist Cervantes in Golden Gate Park. He also designed the faces of a half dollar coin commemorating California’s 75th year of statehood.

Jo Mora with column capital he sculpted for Monterey County Courthouse, Salinas, CA. Used With Permission of jomoratrust.com

After admiring the artist’s childhood sketches in the library’s display cases, I turned to Mora’s map of the Grand Canyon with its conspicuous dendritic side canyons. I located Yaki Point and the Kaibab Plateau to get my bearings, and then noticed, embellishing the area to the east, cartoon figures in headbands with broad paint brushes slathering the Arizona landscape under the sign, “Painted Desert.”

Such literal renderings of place names are sprinkled throughout the Grand Canyon map, prompting smiles: Battleship Rock, Coronado Butte (a conquistador), Bright Angel Canyon, Solomon Temple (a sage) and more are embodied beside their labels.

Pictorial Maps

Mora used the French word, carte, to refer to his pictorial maps. Precursors of the concept go way back—picture dragons at the uncharted edges of medieval maps, and, more broadly, ancient pictographs. The 1914 Wonderground Map of London Town, created by MacDonald Gill, is considered seminal for its use of color, characters, and humor (Hornsby, 2017).

On this side of the Atlantic, “the form flourished in American popular culture,” according to Glen Creason, the L.A. Library’s longtime map librarian and curator of the Mora exhibition. Pictorial maps were employed to promote railroads, automobile clubs, and chambers of commerce (Mora created one for a cruise ship line) and their kinship with comic books is clear. They offer bountiful information as they entertain, and Mora’s “cartes” epitomize the form.

Whatever you call them, Mora’s maps are exceptional for the stories they tell. Many are bordered by panels that describe local history, folklore, and points of interest. One shows history as a procession of period clothing from hoop skirts to tennis wear. Another recounts land development milestones, from Spanish mission to U.S. government survey to the town’s first subdivision plat.

Journey West

Detail from 1933 map by Jo Mora, commissioned by Grace Line to advertise cruises through Panama Canal. David Rumsey Map Collection

In addition to maps, an assortment of Mora’s work is represented in the library exhibition, including journal entries, watercolors, posters, photographs, and sculptures, much of it original art, with museum labels describing key parts of his life journey.

At age three, Joseph Jacinto Mora (1876-1947) immigrated to the United States from Uruguay via Spain with his parents and brother. He grew up in the East and worked as an illustrator of children’s books and for the Boston Herald. Perhaps inspired by news from the region and its popular portrayals, Mora longed to go west. In his twenties, he traveled to California and took up residence at a ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley, where he practiced horsemanship and the ways of the Spanish vaquero (cowboy).

Captivated by Native American culture, Mora crossed the Mojave Desert by mule-drawn wagon to Arizona where, for two and a half years, he lived among the Hopi and Navajo people. Biographer Peter Hiller describes that Mora arrived “with an open heart”—not to take from Native culture, but to understand it. He studied indigenous languages, sketched and painted, and recorded his experiences in words and images.

“That’s the Hopi land I’m getting now to know,” Mora wrote in 1904 with some unease: “and to think that in a very, very few years all this will be gone, for the Government is doing all in its power to stop their dances and ceremonies” (Hiller, 2021). Today, Mora’s photographs and realist drawings from that time are invaluable historical documents (E. Glenn, 2008, “Ceremony”). Eight watercolor prints by Mora of costumed Hopi Kachina dancers are included in the exhibition.

Following this formative period, Mora returned to California where he and his wife Grace started a family. During his prolific career Mora was a painter, sculptor, cartoonist, muralist, diorama maker, book author and illustrator, and, in the final decades of his life, mapmaker.

Mapmaker

Bas-relief of Justice, 1937, by Jo Mora for Monterey County Courthouse. Used With Permission of jomoratrust.com

Mora’s bird’s-eye view carte of Yosemite is packed with his characteristic wit, including edgy tourists on precarious mule rides and personifications of El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall. Mora and his family enjoyed visiting the national park, and the map’s lead inscription sets forth its spiritual aim: Upon witnessing Yosemite’s “Grandeur[,] … a bit of humor may help the better to happily reconcile ourselves to the triviality of Man.” You can get a jigsaw puzzle of the carte even now from the Yosemite Conservancy.

Mora produced two state maps of California years apart, and the exhibition’s labels point out the mindsets—pre-Depression (1927) and immediate post-World War II (1945)—that they put forward. The first map, drawn during an economy blithe to the disquiet on the horizon, touts the “Playground of the World” (but challenging that sunniness is an Owens Valley saboteur on the water pipeline to Los Angeles!), while the second exudes American “vitality and economic power.”

For better and worse, Mora’s maps reflect their early twentieth century milieu. Creason notes that some of their cartoonish depictions of African Americans (or widely, their marked absence), Native Americans and others abetted racist stereotypes, while Spanish colonial figures appear ever rosy. The esteem Mora felt for Native Americans apparently did not hold him back, in his Carmel map for example, from mocking the aboriginal residents who greeted the Spaniards. Acknowledging this facet of the maps more forthrightly would have improved the cultural context and education the exhibition provides.

Sculptor

Hopi TÉU-MAHS Káchina, 1904, Lithograph I/XXV, watercolor by Jo Mora. Used With Permission of jomoratrust.com

Mora was a wonderfully expressive sculptor. He described sculpture as his “spiritual inheritance” from his classical artist father, and it was the focal point of his career long before he designed maps. That work is represented here by examples of cast bronze statuettes of western personas, broncos, and a pocket-size bear cub.

I was particularly moved by a sepia photograph of an original plaster model (the first step in making a bronze) that Mora sculpted soon after his time in Indian Country. The Hairdresser was never cast in bronze, and the photograph is all that survives of this three-dimensional likeness.

The sculpted scene depicts two women sitting on the floor, one with her hair gathered in braids that lay forward to expose the back of her neck, which in the photograph is toward us. A visible sliver of her profile shows purpose as her hands, hidden from our view, attend to the side of her companion’s head. The companion, who faces us and leans toward her stylist, appears contented.*

While pictorial maps, like all maps, are time-bound and naturally become records that illustrate the past, Mora’s expression in The Hairdresser of that suspended moment between two souls, gesture and acceptance, their poses and manners gently imparted, is timeless. To see it is to recognize what it is to be alive. ◾

Lloyd Pilchen is a partner at Olivarez Madruga Lemieux O’Neill llp in Los Angeles and serves as legal counsel for cities and public agencies. He is a California and Illinois surveyor. Law Land Lines™ offers Lloyd’s take on the law.

Bibliography

Peter Hiller, The Life and Times of Jo Mora: Iconic Artist of the American West (Gibbs Smith, 2021).

Stephen J. Hornsby, Picturing America: The Golden Age of Pictorial Maps (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2017).