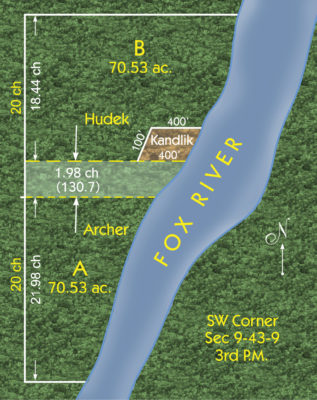

The difference between the PLSS schematic vs. the will of the of grantor was clearly supported via the legal descriptions. Graphic courtesy of Joel Cheves.

Okay, I admit that I got lost in the chain of title right off the bat. So we’re going to cut right to the chase, then hit rewind to find the details. Here’s the spoiler alert. The Majority rightly affirmed the lower court’s ruling that the fence controls but they did it for the wrong reasons according to the “specially concurring” Justice Stone. That’s pretty ballsy and I’m digging what this cat is laying down. Justice Stone’s big beef is with his colleagues’ citation “Boundary lines may be fixed by parol agreement or by acquiescence when supported by possession in harmony with such agreement. (Berghoefer v. Frazier, 150 Ill. 577. )”. The Honorable Justice asserts that this citation is just too broad to be effective. He feels that something is missing so he fills the hole with a reference to a very early Illinois case Crowell v. Maughs, 2 Gil. 419.

“It is a familiar doctrine of law, that title to real estate cannot be transferred by parol. It is settled, however, that proprietors of adjoining tracts of land may, by a parol agreement, settle a disputed boundary line between them. Such an adjustment of the boundary, if followed by corresponding possession, may be binding on the parties, not because it passes title, but because it determines the location where the estate of each is supposed to exist. — Jackson v. Dysling, ٢ Caines, ١٩٨; Kip v. Norton, ١٢ Wend. ١٢٧.» I’ve added the emphasis to the real goodies in there. The “Berghoefer” standard does not seem to consider the motive behind the agreement. Justice Stone quickly points out that the citation might act like a blank check for parol conveyancing without a standard of “uncertainty” being observed.

The courts continually point us to the common grantor in a chain of title. If we go all the way back to Kandlik’s common grantor we see something that blows apart just about every propped-up inference of acquiesce that ever entered a courtroom. Evidence shows that the original subdividers chose to mark a line defining the boundaries based on their own free will as the basis of a land partition. The subsequent owners did not acquiesce to these lines, but in fact they were bound to them. Somewhere in time a fence was erected on the same line. Despite the inconsistent descriptions adopted over the years, the owners continually respected the position and integrity of the line AS IT WAS CREATED UNDER THE ORIGINAL GRANT, and yes I’m shouting! There simply was nothing to acquiesce because everyone lived lawfully under the terms of the original grant. As far as the descriptions go, oh well, que sera sera, tow-may-tow, toe-mah-toe and who cares. Everyone concerned knew what the heck they all meant and furthermore respected their neighbors. Justice Stone must have recognized this and thus kept his colleagues from inadvertently impacting the standard of care.

So let’s review the question that the court faced. “The sole question to be settled by this litigation is whether the descriptions in the deeds…shall be treated as referring to (The PLSS) or as restricted by the line created by the so-called voluntary division arising out of the Thomas deeds of 1848.” I’ll rephrase this. Did the original grant mean something other than the PLSS? The answer was an overwhelming yes! The original grantors did a great job of expressing their desire to decouple the chains of title from the PLSS schematic. Let’s have a peek at the tasty licks laid down in the original deeds. By the way, you’d be hard pressed to convince me that these descriptions were not professionally prepared way back in 1848. This is survey quality stuff and the proof came a century later at the Supreme Court Bench. The descriptions are

“Commencing at a post on the southwest corner of said section 9, thence north two degrees east 21.98 chains to a post, thence north 89 1/2 degrees east 39.82 chains to a post on the west bank of Fox river, thence with said river down-stream 27.20 chains to a post on the south side of said section 9, thence south 89 1/2 degrees west 24.67 chains to the place of beginning, containing 70.53 acres more or less”, and

“Beginning at the quarter post on the west side of said section 9 at the northwest corner of the southwest quarter of section 9, thence south 87 degrees east 41 chains to a post in the center of said section, thence south two degrees west 7 chains to a post on the west bank of Fox river, thence with said river down-stream 8.90 chains to a post, thence south 89 1/2 degrees west 39.82 chains to a post on section line, thence north two degrees east 18.44 chains to the place of beginning containing 70.53 acres more or less”.

So, here’s the tasty totals:

- 2 descriptions clearly authored by the same person showing the same intent for both descriptions.

- 2 adjoining descriptions that fit together by the numbers with survey grade measurements.

- 2 co-currently authored descriptions expressing a precise division of a common tract in half by area.

- 3 calls for posts at PLSS aliquot positions.

- 6 calls for posts at distinct non-PLSS positions.

- 4 calls to artificial monuments set at a natural monument.

- 2 calls to non-PLSS posts falling on a PLSS line.

- 1 call each to the common line with the exact measurement reflected in both descriptions.

- 9 (and every) call containing a physical start point, direction, distance and physical end point.

- 2 of the finest examples of retractable legal descriptions ever written. Really, they couldn’t be any better. For the most part and in common speak I suppose these are best labeled as metes and bounds descriptions. I assure you they both close perfectly and express no conflict between each other. Now, I know the paperheads down at the tax map office will blow an O-ring because there’s no bearing on the riverbank calls and their organ grinder can’t crunch numbers it ain’t got. So, party foul in the land of outer Cogovia, boo flippin hoo. The crafter of this legal description knew the migratory properties of watercourses and cleverly bound the line to its riparian state by forcing the call without a bearing. Brilliant! So here’s the return on your ten minute intellectual investment with The American Surveyor. Use your words!

Huh, that’s it? I know that sounds like the classic movie line ordering little Ralphie to “Drink more Ovaltine” but through careful and strong wording we clearly see the intentions of Kandlik’s predecessor here a century and a half later. And not just us, but the lawyer folk and the courts as well. Perhaps the strongest expression in the “Kandlik descriptions” is that both ends of every line are called out with a physical object. The intent is bolstered by the call for record (legal) objects at certain corners as they existed at the time of the grant. Limiting the call to an aliquot line is an expression of “what the corner isn’t” and separates it from a known aliquot corner position. Finally, an accurate set of measurements is provided to guide us to these intended positions. Legally this is “three rings of steel” wrapped around each corner. Furthermore, every one of these features is backed up by a well settled order of precedence should any of the elements conflict. These instructions effectively become part of the grant and consequently enable the successors, heirs, and assigns to cleanly understand the notice surrounding the original grant. That’s the power of the survey. Incidentally, and getting off track for a minute, I’m compelled to believe that Jefferson’s legal training had more to do with him establishing the PLSS than his ability to measure. Gnaw on that a while.

The deliberate association with and decoupling from certain monumented PLSS corners really nails down the intent of Kandlik’s predecessor. I believe that the author clearly defined his standard of care and cleanly provided his retracement instructions within this these legal descriptions. I have traditionally crafted my descriptions similarly and you can blame that on my Midwestern upbringing. So I leave you with a childhood fairy tale as told to me by Mother Foose.

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall (The original notice of the land partition), Humpty Dumpty had a great fall (Erosion of the original evidence coupled with ambiguous records); All the king’s horses and all the king’s men (This is us) couldn’t put Humpty together again…so they lawyered up. The end!”

A special thanks goes out to Jim Hankins of Illinois for sending this case to us and providing the wonderful graphics. I had the opportunity to meet with Jim while I was presenting at the 2019 IPLSA Conference in Springfield, Illinois. Jim is an extremely knowledgeable and well-seasoned land surveyor. He chatted about the benefits of the local laws encouraging surveyors to participate in boundary agreements and formal resolution of disputes. It seems like a fitting role to emancipate folks from litigation and reunite divided owners under law in the Land of Lincoln. Thanks for the insight Jim!

Sidebar:

Required Reading

I am always on the prowl for land surveying resources and have hit pay dirt along the Columbia River. A $35 donation to the Oregon Professional Land Surveyors Association will get you an electronic copy of “The Land Surveyors Guide to The Supreme Court of Oregon Volume One-1848 Through 1892 Building The Foundation of Our Law” by Brian Portwood. The work is classified as “Interesting and informative cases involving the establishment and documentation of land rights and related principles of law and equity”. That is no lie. I have not been able to put this book down from the minute I picked it up. They call this “binge reading” and it’s what we used to do before Netflix came out. Anyway, Brian just knows how to take dry material and get right to the meat. He’s included great graphics of original plats and sketches as well. This 391 page work is a must have for every practitioner in the PLSS and the Colonial States. The national value of this otherwise local collection lies within its presentation of the Courts’ behavior regarding land rights, and the principles of law vs. equity when evaluating boundary issues. As Brian points out, “While knowing the law well enough to practice law is the sole domain of the legal profession, simply observing how the law is implemented holds many highly valuable lessons for land surveyors, because only after having seen how land rights issues are judicially resolved can one achieve a reasonably complete understanding of the proper role of the land surveyor in our society.”

Brian Portwood, P.S. is no stranger to our readers and certainly has V.I.P. status here at Decided Guidance. He helped us out back in June 2018 with Hoyne v. Schneider. Brian has developed a format and created six volumes of “Land Surveyor’s Guides to The Supreme Court of…” which cover the states of North Dakota, Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado respectfully. His work is available through bportwood@mindspring.com and the Oregon publication is available through the PLSO website store www.plso.org.