How Important is a Chain of Title?

Our last trip to Old Dominion chronologically ended up being in the Bluegrass State. This month we are in the Commonwealth of Virginia “proper” visiting a case situated in the City of Virginia Beach. These subdivisions incidentally are in the exact spot where English Common Law set foot on the continent way back in 1607. A special thanks to the City Surveyor of Virginia Beach Dwight Spivey for his assistance in tracking down these plats. By the time this gets to print Dwight should be retired and hitting the links full time! I enjoyed the opportunity to hear him reflect on his career and recollection of his first day surveying way back before automation. I can’t over emphasis the importance of harvesting local knowledge and the professional camaraderie that’s out there. Best wishes Dwight!

Okay, On to the case. The syllabus says “In dispute over title and right to possession of land surveyors appointed by the court were unable to agree. Plats of record and not of record together with deed descriptions and surveys showed overlap. Plaintiff must trace unbroken chain of title to Commonwealth or common grantor or prove state of facts warranting presumption of grant. Prior peaceful possession [is] not sufficient where [the] defendant [is] not an intruder or trespasser without color of title.”

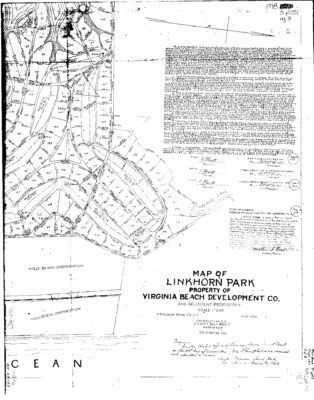

This case is what I normally think of when I hear the phrase “boundary dispute.” Two separate parties with two separate chains of title describing the same chunk of dirt on the ground or “overlap.” The court sums it up as follows: “Both Page and Luhring claim title and right to possession of the disputed land under the respective plats referred to in their deeds. Neither party claims title by adverse possession or the presumption of a grant. Thus the crucial question presented is whether Luhring presented sufficient evidence to prove record title to the disputed land.” This is a matter of law. We know where the land is, we just don’t know who rightfully owns it. Needless to say the original subdividers crossed ropes on this one so we had to call in “all the king’s horses and all the king’s men.” Surveyors, title examiners, lawyers, and boy howdy this was an “all skate” as they say down at the rink. As the court put it “The Hollies plat of 1884 is “manifestly ineptly drawn” and long has been regarded as unreliable by title examiners, surveyors and civil engineers, who have resorted to two unrecorded plats of The Hollies on file in the office of Baldwin and Gregg, Civil Engineers and Surveyors, prepared in 1926 and 1938;.” Remember back in April where I said “I have yet to run up against a case where the Court throws out the plat and calls a mulligan”? Well, I think I just spun one up here and ironically it’s a golf course.

I was pretty hard on the “Halverson Panel” (see TAS Feb 2018) because of their trouble interpreting a single plat. After taking a look at these two plats it’s not too hard to see why our rope stretchers in this case were all over the map, pun intended. “Frank G. Tarrall and P. Porcher Gregg, expert land surveyors, were appointed by the court to study the ownership of the disputed area and to make a finding as to the boundary line between The Hollies and the Linkhorn Park plats, but they were unable to agree. Tarrall testified that after viewing the plats of record, plats not of record, and making a survey of the property, he was of opinion that none of Page’s lands bordered on the shoreline of Crystal Lake and that the western boundary line of his property was the east side of Holly road. He was also of the opinion that the eastern boundary line of Luhring’s site 58 was the west side of Holly road.” It sounds like Tarrall was hookin’ it all up, right? He was able to reconcile the plats with the events and places on the ground. Shouldn’t that be the end of the story?

“Gregg, a partner of J. M. Baldwin until his death, and now a member of the firm of Baldwin and Gregg, testified that he was unable to locate the field notes used by Baldwin in the preparation of the Linkhorn Park plat. He was of opinion, however, from an examination of the plats, deeds and surveys, that there was an obvious overlap between the plats of The Hollies and Linkhorn Park; that the eastern boundary line of the Linkhorn Park plat had been erroneously extended by Baldwin to include a part of Page’s land shown on the Hodges plat of The Hollies; that the western boundary line of Page’s property runs along a part of the eastern shoreline of Crystal Lake; and that Page was the owner of the land in the disputed area.” Now this is interesting. J.M. Baldwin was Gregg’s partner and laid out the Linkhorn Plat. Apparently Gregg was the heir of the “institutional” knowledge and keeper of the original records. He recognized an error and brought it forth to the court. Shouldn’t that be the end of the story? Well, it wasn’t and I can only speculate the court saw confusion on the ground. Let’s rehash the trial court’s take on the Hollies Plat. “The Hollies plat of 1884 is “manifestly ineptly drawn” and long has been regarded as unreliable by title examiners, surveyors and civil engineers, who have resorted to two unrecorded plats of The Hollies…”. This sounds an awful lot like what field guys might call a “stink pickle.”

So, the trial court ended up respecting the Linkhorn Plat and finding that Luhring was the owner of the property. The unrecorded versions of “The Hollies” plats apparently reflected Holly Road and some had some continuity with the Linkhorn plat. Regardless, Page felt that the trial court erred because 1.) Luhring did not trace his chain of title back to the Commonwealth or to a common grantor; and 2.) The court relied on Luhring’s independent examination of records in the clerk’s office in deciding the case.

Back in the March 2018 Barbershop Barrister section I had blathered on about running a chain of title (COT) back to patent or at least to the subdivision plat. Well, here’s the official guidance folks. “As a general rule, in an action in ejectment as well as in a proceeding under Code | 8-836 to establish a boundary line of coterminous lands, in order for a plaintiff to prevail he must do so on the strength of his own title, and when he relies on his own paper title he must trace an unbroken chain of title back to the Commonwealth or to a common grantor or prove such a state of facts as will warrant the presumption of a grant. Brunswick Land Corp. Perkinson, 146 Va. 695, 704, 707, 132 S.E. 853, 856, 857 (1926); Prettyman M. J. Duer & Co., 189 Va. 122, 136, 137, 52 S.E.2d 156, 163 (1949); Development Corp. Jackson, 201 Va. 95, 99, 109 S.E.2d 400, 403 (1959).” This is, of course, Virginia law so the folks of your local bob danglers guild may say things like “This does not apply in our state!” or “My client doesn’t want to pay for that!” They would be very remiss in their assumption but perhaps correct that 1.) It is not codified in your jurisdiction and 2.) Cheapskate clients hire half-assed surveyors. A chain of title is as much a functional part of a retracement survey as is linear measure. Two PLSS cases come to mind supporting the fundamental need to understand the chain of title. We spent a lot of time on Bryant v. Blevins in the autumn of 2017 and covered Wood v. Mandrilla in September of 2016. In Bryant we saw by running back to a common grantor that a sequential “half” may have had a senior right. Although it did not appear material to the case it became evident through our examination of the COT. In Wood we found out that the patent only described the perimeter of the boundary. This in turn affected subsequent reliance on the G.L.O. plat. Tracing the description all the way back to the original grant was a critical element of that case.

The Supreme Court respected Page’s appeal and found that “…Luhring has failed to trace an unbroken chain of title back to the Commonwealth or to a common grantor. He claimed that the land in the Linkhorn Park subdivision was carved out of the 1200-acre tract shown on the plat of Virginia Beach, but Luhring’s title examiner could not say which description in the deed conveying the acreage covered the property in dispute despite his conclusion that the property in the Linkhorn Park plat lay within the boundaries of the property shown on the plat of Virginia Beach. Moreover the deed to the 1200-acre tract made no reference to Oyster Bay or Rainey’s Pond (Crystal Lake).” Take notice that the Court was looking for a bounding call and a record or natural monument in the deed but didn’t find one. Perhaps the court is asking us to give them more than math in our legal descriptions, ya think?

Our second trip to Virginia was just as enjoyable as our first. I reiterate that colonial retracement work is enriched with centuries of behavior bolstering the chains of title. In that respect the future of the PLSS is in “the present” of Old Dominion. Gnaw on that a while and see what sinks in. Feel free to send feedback to the editor or me at rls43185@gmail.com.

Notes: The case text for Page v. Luhring can be found at https://amerisurv.com/docs/PageVersusLuhring.docx

Sidebar:

The Barbershop Barrister

Page does something really bold in this appeal. He calls the trial judge out on the carpet for “…relying on his (Luhring’s) independent examination of records in the clerk’s office in deciding the cases.” The trial judge had the following testimony to work with. “Henry T. Marshall, an attorney, who examined the title to the properties on behalf of Luhring, testified that in his opinion Luhring had a good and marketable title to the disputed land…He (Marshall) was unable to reconcile the northern line of this plat… (and) he was unable to identify any description in the deed which extended the eastern boundary line of Luhring’s site 58 over and beyond the western boundary line shown on the Hodges plat of The Hollies.” Let’s talk about “marketable title” for a minute. Cornell Law School offers this definition in their online dictionary: “Title that is free from reasonable doubt or any sort of threat of litigation. An implied promise in a contract when a seller is selling land to a buyer is that the seller will deliver marketable title to the buyer at the date of the closing. A title to a piece of land is considered unmarketable if there are encumbrances on the land, such as mortgages, unless the buyer waives them. Title is also unmarketable if the land was obtained through adverse possession, or if the land violates any zoning laws.” Title insurance and escrow help grantors snuff up their title for “the closing” and theoretically soften the “War” in “Warranty Deed.” This case however ended up in litigation. With hindsight I question if it really did have marketable title? Remember, Page appealed and won because Luhring failed to trace an unbroken chain of title back to a common owner or commonwealth.

I walk away from this case thinking Luhring apparently did not have good title regardless of the title expert’s opinion of marketable title. I also think the terms “good” and “marketable” are not synonymous when it comes to title. I equate good title with facts and marketable title as subjective. It is imperative that we understand how title insurance differs from a chain of title and what the surveyor requires in a retracement performed outside of the ALTA/NSPS arena. By the way those “NSPS” standards can be found at nsps.us.com/?page=ALTAACSMStandards Let’s all throw horns up at Gary Kent and Curt Sumner as we drive by.

The title insurance “policy” is a document prepared for a grantee or his lender attempting to disclose or offering “to make right” title defects apparent in the county records. The policy issued by an underwriter is based on a calculated risk determined by some assessment of potential harm. I suspect in that context it’s like most other insurance policies, at least to a lay person’s eyes. I recall from my past, questioning the apparent foolishness of issuing a title policy on a new home when a location survey showed the new gravel driveway encroaching for a few lineal feet on an adjoiner. The title man asked if I had a handle on the risk. I offered “The price of litigation?” He replied “Nope, two hours of labor and the price of a rake, we’re issuing the policy.” Ah-ha-hal-righty then and God bless you Dave Mough for that reality check. The point being that a title policy is a contract between two parties that don’t include you and may favor the potential for harm over facts of record.

A chain of title (COT) on the other hand is a sequential collection of facts demonstrating the birth and conveyance of title. It could be looked at as the backbone of a title insurance policy but perhaps most particular to rope stretchers is the evolution and stability of the recorded description as the chain is (…and here’s your “fiddy cent” word of the month) promulgated through history. Theoretically the chain of title is part of the title examination and policy. However, the underwriter does not normally show the chain and has full discretion to accept flaws based on some risk assessment. In other words the underwriter can issue a policy based on title that is “free from reasonable doubt or any sort of threat of litigation.” The short story is be certain that YOU examine the chain of title and see all documents for your intended purpose of…yes, retracing the original survey and grant. There’s certainly nothing wrong with farming out the service to a title company, abstractor, or examiner. In fact seven Midwestern states require licensure of title examiners. What is necessary as the owner’s surveyor is that you 1.) Understand the COT as you prepare your survey and 2.) Can factually represent that to your clients before they drag you onto the witness stand. Identifying anomalies in a COT prior to establishing anything on the ground places you in control of the field. Writing a contract that obligates the client to present good title, or a path thereto, before you complete a survey might just keep you out of the courtroom. Presuming your clients will need the chain of title to stand on your survey in court, why don’t you provide one to them with your deliverables? If your response is “extra cost” I’d caution you not to answer out loud. Here’s your point of order paid upfront: “Frank G. Tarrall and P. Porcher Gregg, expert land surveyors, were appointed by the court to study the ownership of the disputed area and to make a finding as to the boundary line…” The Court is gonna need it, so you can get it early or the opposing side’s consul can get it later.

So, we found out last month in Maine that “what the boundaries are is a question of law, but where the boundaries are on the face of the earth is a question of fact. Liebler v. Abbott, 388 A.2d 520, 521 (Me.1978).” Today we also see that the Commonwealth of Virginia expects the surveyor to understand the law and land title in so far as required to locate boundaries. As quoted in the previous paragraph the court appointed the expert surveyors to study the ownership. That’s still on the “factual” side of the Lieber guidance but a whole hell of a lot different than “I wasn’t requested to make a survey of property rights, just Lot 6, Block 31” as we heard in Wacker v. Price back in May of 2017. So yes, there’s a little more to retracement work than just pulling up in a beater truck with a “borrowed” RTK rig and charging the landscapers hourly rate for weekend beer money.