So far we have learned about the State Lines between Texas-Oklahoma in 1929 and the State Line between Washington-Idaho in 1909. Now we will step a little bit further back in time to the days of a younger and less experienced Samuel Stinson Gannett. We will cross the panhandle of Idaho and study the Idaho-Montana State Line and see how he helped place this imaginary line on the ground in some of the roughest terrain in the West.

Plate XIII of USGS Bulletin No. 170 titled “Summit Of Bitterroot Mountains, Showing Pack Train Loaded With Sections Of Granite Monument”.

The State of Montana came from a portion of the Idaho Territory. The Idaho Territory was organized on March 03, 1863 from part of the Washington Territory. The Montana Territory was organized on May 26, 1864. Montana became the 41rst State on November 08, 1889 and Idaho became the 43rd State, following Washington, on July 3rd, 1890. Both territories were approved by President Abraham Lincoln. Once again, amazingly enough, the two States shared a common boundary. According to Richard Goode in Bulletin 170 titled Survey of the Boundary Line Between Idaho and Montana the Western Line of Montana is “…thence westward and northwestward, following the line of the continental watershed and the summit of the Bitterroot Range to its intersection with the thirty-ninth meridian; thence north on the thirty-ninth meridian to the boundary line between the United States and the British possessions…”. This seems simple enough but the 39th Meridian was measured from Washington D.C. at the Old Naval Observatory.

This Meridian was defined by Congress on September 28th, 1850 as the center of the original dome of the observatory and held until 1897. The United States Congress on August 22nd, 1912 repealed the American Meridian(s) all together yielding to Greenwich. Technically Washington D.C. has had four different Meridians, one thru the Capital Building, one thru the White House and two through the Old and New Naval Observatories. Over a dozen different States and former territories have their boundaries in relation to the Old Naval Observatory Meridian. The government had ties to this Meridian across the Country and the closest to the Idaho-Montana State Line was in Spokane, Washington. On the grounds of the court house in Spokane were a set of astronomic piers as established in 1888 by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. With the precise longitude in Spokane and a given correction between the Old Naval Observatory Meridian and the Greenwich Prime Meridian the State Line could be calculated. The Greenwich Meridian longitude of the center of the dome was 77°03’02.5″. Adding 39° to this equated to the State line between Idaho and Montana being 116°03’02.5″. The first monumental task was getting this longitude (and latitude) across the panhandle of Idaho.

The disk on Monument 83 stamped “63.03 M” being 63.03 Miles from the Initial Point and lying outside of Cabinet, Idaho. Photo Courtesy of Kurt Luebke

Samuel was 35 years old when the field work started from Spokane. Known for his quiet demeanor he was nicknamed Silent Sam. The first observations on this survey were to determine latitude at the Spokane longitude monument and were performed by Samuel. During the twilight hours of August 6-9, 1896 Samuel calculated the latitude by making fifty nine observations of twenty seven different pairs of stars. The latitude pier of which he worked still exists today as does the courthouse. Monumental efforts have been made to preserve the pier led by The Land Surveyors Association of Washington and Jim McLefresh. Next the baseline was measured with a three hundred foot calibrated steel chain for a distance of five miles heading east out of Spokane along the former Northern Pacific Railway.

This was done by measuring to a scribe on a zinc strip nailed to a smaller board that was nailed to a larger board that was nailed to the railroad ties at three hundred foot intervals. The total distance for the baseline was 26,404.641 feet. Once the baseline was complete an azimuth was computed between the intervisible base line monuments. This was done by occupying the West Base and measuring the observed angle between Polaris and the East Base. On the night of August 15th, 1896 eighteen different observations were made creating the base of the series of three separate figures and nine separate triangulation stations. At first the triangulation was done by 33 year old Edmund Taylor Perkins Jr. nicknamed Rolly. He surveyed until October of that year when the snow became too deep to travel any further. He packed up and traveled to California for the winter. During the winter months Silent Sam calculated the least square positions of the nine triangulation stations that were occupied in 1897.

Sectional Monument 92 stamped “70.717 M” being 70.717 Miles from the Initial Point and lying at the Summit of the Bitterroot Mountains. Photo Courtesy of Kurt Luebke

The survey party didn’t hit the field again until June of 1898. It was then that Rolly continued with triangulation and Silent Sam and Dewitt Reaburn started running a random line north. After finding a 117 foot bust in their calculations they calculated the initial point and ran their random line north until October 31rst, 1898. When they stopped there was 2 ½ feet of snow on the ground and the terrain they Granite Monument 83 outside of covered was beyond what they could have imagined. At the end of this season it was calculated that the crew traversed approximately 63,000 vertical feet over 72 miles. With an average stadia sight distance of 350 feet it totaled 1,051 different transit setups. Once again it was June of 1899 when field work started. The winter months were again used for calculations of the random line in relation to the true position. This final season of field work was broken up into four units, three for triangulation and one for accurate chaining of the northernmost section to compare to the stadia measurements. Once this was complete the final line was monumented starting at the north end and moving south. All field work was completed by October 5th, 1899 when the party dispersed and went their separate ways.

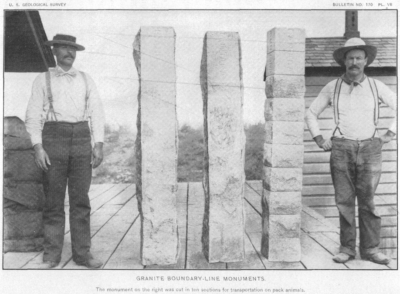

The monuments set from north to south were specific in their nature. Unlike most State Line boundaries the monuments were placed at convenient geographic positions. Only a few circumstances did the geography lead to monuments more than a mile apart, the average spacing be three quarters of a mile. They consisted of granite and iron posts. Originating from Medical Lake, Washington the granite monuments cost $14.50 a piece delivered to the nearest railroad station requested. They were six feet long and ten inches square. With roughly eighteen inches dressed on the top most portion, they bore the words “Idaho” and “Montana” on opposite sides. On occasion these monuments were cut into ten sections so they could be loaded onto pack mules for transport. They were then bolted together and affixed with cement. The iron posts were also six feet long with a diameter of four inches. The posts were coated with tar to aid in preservation. The bottom was flared to twelve inches and the posts were to be set three feet in the ground where possible. The top of these posts held a bronze cap with the Mile Post stamped in it as it originated from the North. The iron posts were made and shipped from St. Louis, MO for $2.08 ½. Each monument, whether granite or iron, was then thoroughly referenced with witness trees, and pits and mounds were dug in cardinal directions.

The 1893 Spokane County Courthouse, Spokane, Washington circa 1915. The 1896 Latitude Pier can be seen in the bottom right.

Prior to this survey the line between Idaho and Montana has only been marked on paper. The railroads cutting through the state line estimated the location but were found to be upwards to a mile off. It is also stated that once the line was ascertained in the field a road thought to be built and maintained by Idaho suddenly became the property of Montana. The final product was a beautifully put together map of the boundary with a full report detailing the location and mile post of each monument. Starting at the custom built stone monument on the 49th degree of parallel and ending at the ten section granite monument number 92, this survey spanning three seasons shall be remembered for its technical degree of accuracy as well as its pure muscle and might it took to get it done. The team of Gannett, Perkins and Reaburn did an amazing job and once again put to rest a confusing and undetermined State Line Boundary.

Author’s note: I encourage everyone to read Bulletin 170 to see the full detail of this survey. I wish to thank many local surveyors for their help in this article, including Denny DeMeyer, Jim McLefresh and Kurt Luebke. Next we will travel to the mouth of the St. Louis River on Lake Superior to study the work of Gannett on the Wisconsin Minnesota State Line. We will see how he followed the orders of the Supreme Court and how he retraced a survey from 1861 and did so in the middle of winter, pulling a chain on the ice.