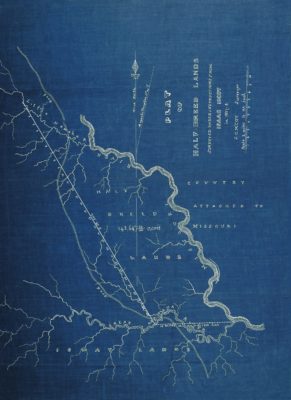

The original plat of the Half Breed Lands in what would later be located in the southeast corner of Nebraska. Courtesy Nebraska State Surveyor’s Office. Displayed with permission

As European-American settlement pushed west in the early 19th Century, various areas were set aside across the country for the Native American tribes. However, a new group of people developed who were the mixed-race descendants of predominantly French and Scottish fur traders and Native American women. These mixed-blood people became collectively known as Half Breeds. Initially, the term Half Breed was purely a descriptive name and not derogatory. These groups found themselves caught between two cultures. They were prevented from being included in the reservation system and were excluded from obtaining land by the usual fashion afforded to whites since they were neither fully white nor fully Native American.

At the Fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chien on July 15, 1830, a tract was created for the Half Breeds of the Otoe, Ioway, and Omaha tribes, and the Yankton and Santee bands of the Sioux. The irregular-shaped tract was bound by the Missouri River on the east, the Great Nemaha River on the south, the Little Nemaha River on the north, and a diagonal line between the Nemaha Rivers on the western side. This mostly unexplored area where the tract was located later became the southeastern portion of Nebraska Territory in 1854.

John C. McCoy of Kansas City surveyed the Half Breed Tract in 1937-38. Courtesy Kansas City Public Library

Seven years passed before the boundaries of the tract were surveyed by John C. McCoy. The Half Breed Tract began at the mouth of the Great Nemaha River at its confluence with the Missouri River. From this location, the southern boundary followed the course of the Great Nemaha to a point on the river that was 10 miles in a straight line from the Missouri River. Similarly, from the mouth of the Little Nemaha River with its confluence with the Missouri River, the boundary followed the river until reaching a point upriver that was 10 miles in a straight line. A diagonal line in a northwestsoutheast direction connected the two 10-mile river points and formed the western boundary. This western line was the only non-natural boundary of the Half Breed Tract and was technically the only side that was not subject to change by natural causes.

Plat showing the disputed area along the western boundary of the Half Breed Tract which placed the town of Archer within the tract. Drawing by Jerry Penry

McCoy began the meanders of the Great Nemaha River by going south and west, crossing below the Fortieth Parallel several times into the area that would later become northeastern Kansas Territory. After traversing 216 river courses, McCoy mathematically determined that he was 10 miles, in a straight line, from where he had started at the Missouri River. The meandered distance which followed the channel of the Great Nemaha River, however, was close to 21 miles. Unfortunately, McCoy did not specifically state where the mouth of the Great Nemaha River was located at the time of his survey in relationship to the bluffs that confined the Missouri River. In this area, the bluffs of the Missouri River are over 6 miles apart and the channel often changed course between these bluffs.

Cozad and his crew of six men departed from Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, on October 5, 1855, and arrived four days later at the Ioway Indian Mission where Cozad hoped to determine the location of the western line. The agent was not present, but others claimed that although they were aware of the proximity of the line, no one had ever seen any monuments along it. Squatters arriving in the area around this time were eager to know where the line was located to select land that would not be within the Half Breed Tract.

One of the few remaining areas where the Half Breed Line still determines ownership as shown in 1965. SE Quarter of Sec. 17, T4N, R15E, 6PM.

After much searching and comparing of notes, Cozad determined that only one line would match McCoy’s stream crossings. A line tree with old markings was subsequently found and upon chopping into the tree, it was determined that the markings were 18 years old. Cozad retraced this line northwesterly to the 27th milepost and then ran McCoy’s bearing to the Little Nemaha River. The crew then surveyed back southeasterly along the line to the Great Nemaha River setting 5-foot tall wood posts blazed on two sides and marked with red chalk “H.B.L.” at every one-half mile location. Other stream crossings along the line closely matched McCoy’s notes, so Cozad felt satisfied that he had correctly retraced the original line of 1838. His point on the Great Nemaha River, however, was 7.5 miles from the mouth of the Missouri River instead of 10 miles. Cozad’s notes were approved by Calhoun and the matter was thought to be concluded after payment of $408.25 for the work.

During the winter months of 1855, Michael McManus began subdividing the portions of the townships located outside of the Half Breed Tract. McManus terminated his section lines at the Nemaha Rivers and upon the western boundary by setting stones where his lines met the boundaries of the Half Breed Tract. By the spring of 1856, McManus returned and surveyed the interior lines within the Half Breed Tract because the government had decided to give individual allotments to the Half Breeds instead of having them collectively reside as a group within its boundaries.

This historical marker sign east of Auburn , Nebraska, brings attention to the Half Breed Tract near the northern end of the western boundary. Courtesy of Jerry Penry.

Word that Cozad’s southern line of the tract was closer to the Missouri River than the specified 10 miles in the treaty, caused leaders of the Half Breeds to claim they were being cheated. The Cozad survey determined that the tract contained only 120,681.59 acres which was nearly 23,000 acres less than what was shown on the McCoy survey. After much discussion, and to fulfill the original intent of the treaty, the GLO decided that a new western boundary should be established on the assumption that McCoy had made an error in 1838.

William H. Godwin received the contract to survey the new western boundary of the Half Breed Tract. His survey began 10 miles from where the confluence of the Great Nemaha and Missouri rivers was currently located and went northwest to the established point on the Little Nemaha. Godwin began his survey in late 1856 and after some delays, finished on October 20, 1857.

1857 map

Instead of setting half mile points on the new Half Breed Line, Godwin instead placed marked stones at each location where his new line crossed the section lines. The half-mile monuments set by Cozad and the closing corners placed by McManus along the original western line were then destroyed. Calhoun approved the survey of the new western boundary of the Half Breed Tract on January 28, 1858.

The new line further west created its own problems. Businessmen in the area had already founded the thriving town of Archer adjacent to and outside the original western boundary. Lucrative trade from this town was being made with those living inside the Half Breed Tract. White settlers who had established claims outside the original line had already made valuable improvements. The new western boundary now placed the town and these settlers inside the tract. They were told to move out.

1857 map

During the confusion, the concerned leaders in the town of Archer held a meeting of the shareholders on July 12, 1858. It was resolved to assess a tax of $5.00 on each share for the purpose of resurveying a new town outside the new boundary. In 1858, Archer was one of the most prominent towns in Nebraska, and the county seat of Richardson County. Because many businesses moved their buildings off the site, the situation ultimately caused the town to lose its status as county seat and the newly platted town a few miles away never developed.

To resolve the issue, an Act of Congress, on February 28, 1859, determined that the value of the unsettled land lying between the two western lines of the Half Breed Tract was to be paid to the Half Breeds. The whites who had established their claims between the two lines and who were initially told to move, were now permitted to stay.

The uncertainty and turmoil over the western boundary prompted Judge Fenner Ferguson, delegate to Congress from the Territory of Nebraska, along with Elmer S. Dundy to travel to Washington D. C. where they successfully lobbied for the passage of a bill to reestablish the original McCoy line as the true boundary.

Since the original McCoy line of 1838, reestablished by Cozad in 1855, was completely obliterated by Godwin in 1857, Alexander Oliphant was contracted by the GLO in September of 1858 to resurvey the original line. Oliphant placed new monuments where the original western line of the Half Breed Tract crossed each section line. He next destroyed the corners placed on the Godwin line. The reestablished original western line of the Half Breed Tract was approved by Surveyor General Ward B. Burnett on October 27, 1858.

Within one year, the Half Breed Tract was dissolved and opened to white settlement making the boundary lines of this tract essentially irrelevant. The efforts and expense to continually define the western line were needless. Only a few isolated locations remain today where land ownership is still determined by the Half Breed Line including a 3.5 mile stretch of county road on the north end. The other sections that were once bisected by the line are now aliquot parts as if the line had never passed through them.