Preface

This article is written from the point of view of a property owner who is suddenly faced with a significant boundary challenge from her neighbor. Without the financial resources to hire an attorney to go to court, or to pay for a land survey, she turned to the statewide surveyor’s organization, the Professional Land Surveyors of Colorado (PLSC) for help. This is a classic case where lot lines were established based on a survey done and monuments placed over 20 years ago, and a more contemporary surveyor, using allegedly original evidence, did not accept the lot lines, resulting in potential chaos in the neighborhood. The Colorado Revised Statutes, 38-44-103 refers to boundaries that “have been recognized or acquiesced in by the parties or their grantors for a period of twenty consecutive years.” But before all of the facts and timeline were defined, this was settled without going to trial, and no lines were moved, resulting in a kind of de facto acquiescence. –JB Guyton, PLS.

Figure 1: Driveway. The fencing to the right is the north boundary fence. The new survey stake, left, was marked approximately 35’ toward my house and runs a distance of 691’.

Having a process server show up on my doorstep was surprising enough. Finding out that my once-friendly neighbor was taking me to court over a supposed boundary dispute was worse. That is what I was faced with last November, just after Thanksgiving.

My neighbor took down my corner T-post at a shared corner between us, a few months prior. The post was marking one of my eight survey monuments, the one easily lost in the tall, summer grasses where there was no permanent fence post. When I replaced the T-post, the sparks flew. The normally cordial neighbor was not so much any longer. He told me in no uncertain terms, he owned a significant amount of land that I knew was mine.

Obviously, I was not amused. After all, I had owned my almost 37-acre mountain property in Livermore, Colorado, for a total of nine years, and lived here five years before he moved in. He sent me a note stating he would be obtaining a new survey to prove he was right. One day I returned home to wooden stakes and new monuments which were put approximately 35′ into my property along the north, east and west boundaries of my home. Quickly following was another note from the neighbor stating I had two weeks to move my driveway and he would be installing new fencing. He also noted he had `helped me out’ by taking down my temporary fence I had erected along my west line.

Figure 2: Meadow. The fencing on the right is my boundary fence, which would have been moved 35’ to the left, into the meadow. This runs a distance of 493’.

The land that my neighbor claimed included my driveway (access to my home) along the north boundary (Figure 1), my meadow along the east boundary, which runs alongside a beautiful spring creek (Figure 2), and 500′ of road frontage along the west boundary (Figure 3). The t-posts or fencing shown indicate my property boundaries, which the neighbor wanted to move approximately 35′, resulting in a loss of quite a bit of land. I could not let that happen. Once I disagreed with this neighbor in writing, I found myself a defendant in litigation. I quickly contacted many area attorneys, who explained that cost estimates might possibly reach the $20,000 range for this kind of case–a property boundary dispute.

At first, I was confused. I had no dispute. I am very confident where my property boundaries are, clearly marked by the existing monuments. These are the same boundaries I based my purchase on nine years ago. So why was there a dispute?

Then I was concerned. I could not afford to hire an attorney because I am a now-single mother of three. So, I attempted to find the 1996 surveyor, as well as the surveyor who originally subdivided the parcels in 2000, both of which confirmed my boundaries. I contacted the Professional Land Surveyors of Colorado (PLSC) to try and locate them. A very kind lady called and listened to my very lengthy problem. She said she could put me in touch with others who might be able to offer information. And I needed a LOT of information!

Figure 3: Road Frontage. The t-post to the right is where my monument is. That is my west boundary, so the road runs through my property. This is where my temporary fence was, which the neighbor took down. This runs a distance of approximately 500’.

For the next six months, I contacted PLSC time and time again, as the Plaintiff’s attorney filed multiple papers with the courts. According to him, the neighbor’s new survey trumped all that went before it and his land was shifted onto mine. Therefore, I was informed he owned a lot of my property and always had. I was supposedly now trespassing on my own ground. I could not disagree more.

With each new court document came 20 more questions I had. And they all pertained to surveying. Asking so many questions that my head was spinning, an advisor from the PLSC, who was also the local director of the NSPS, answered each one and probably repeated most of those answers a multitude of times. Since I was not familiar with this field, I needed repetition for the facts to stick. Especially since the Plaintiff’s attorney was disputing everything I claimed was fact.

The neighbor also did not want to acknowledge there were adjoining homeowners who would be affected if the judge agreed the new survey would supersede the 1996 survey. All my property boundaries could possibly shift onto and over adjacent landowners. The neighbor was only concerned that his new survey was right and the `disputed area’ was his.

Aerial view of neighbor’s property, with the author’s land to the south and east. The red line indicates the more recent survey that created the disputed areas. Click to enlarge.

So, I forged ahead, trying to learn a new language–that of surveying. I am a freelance writer and editor but have never had the opportunity to research this field. My advisor not only gave me facts but educated me on the history of its interesting beginnings and how surveying operates. This was a fascinating subject and learning it offered me a leg up on the neighbor, I believe. It also gave me the vocabulary I needed when writing my lengthy court documents. Because of my advisor’s help, I felt well-versed and able to put together responses to the Plaintiff. But most of all, he gave me the confidence I needed.

The neighbor’s house was for sale throughout this whole ordeal and by April, he had a buyer. At that point, he decided he was going to sell all his land, except for the `disputed area.’ This he was going to retain title to. The only problem with that was–it was my land. That `disputed area,’ which he liked to call it, was where the new survey pushed over my land–my driveway, my meadow and my road frontage. “He can’t retain title to something he did not own,” was my defense. I had to again reach out to my advisor and get more information.

The neighbor then offered a `settlement.’ He would give me two of the three distinct `disputed areas’ and keep the third. That third was the 500′ of road frontage. I knew I could not give up land and he could not `give me’ what I already owned. After another lengthy conversation with my advisor to gather facts, I again told the Plaintiff I would not agree to this `settlement offer’ and trudged forward, confident in my knowledge of surveying that I had acquired. Threats of additional lawsuits followed.

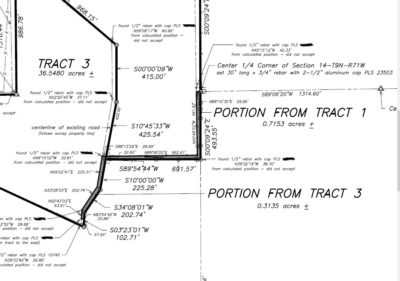

A portion of the most recent survey, based upon a 2017 interpretation of section lines which are inconsistent with settled parcels, resulting in the approximate 35’ wide conflicting boundaries, shown as shaded areas. Click to enlarge.

But then, just as quickly as it started, the fiasco ended. I was contacted by the neighbor, not his attorney. He asked me if I would agree to a dismissal of the case. I agreed to dismiss with prejudice since I could not allow this to happen again in the future. And within a few hours, the paperwork was signed, and all was as it had been. I own the land I always had owned, and he or the new owners, retained theirs.

Although this was a trying situation, I was thankful to have met individuals at PLSC who made it less so because they were willing to take their time and share their knowledge of an industry I was unaware even existed just a few months earlier. I was able to stand confident and true to my boundaries throughout this litigation. Thank goodness for the folks at PLSC who live according to one of their purposes:

To provide educational and instructional opportunities for those persons presently licensed as land surveyors within the State of Colorado, and for any other persons who are in any manner interested in learning of the profession of land surveying.

I have retained my land and acquired a new language where I can speak more confidently about surveys, monuments, lines, boundaries, sections, townships and ranges. But more importantly, I have a great deal of respect for the occupation of surveying and how these men and women divided our land for all of us to enjoy. Without PLSC, I do not know how this would have turned out. But I am sure that it would not have been as happy an ending for me.

Editor’s note: For those of you who have been reading the magazine, many of the legal cases involve acquiescence. The thought that a new surveyor can come along and mathematically “prove” that long-relied-upon corners do not represent the corner is preposterous. This story represents a great example of helping an innocent landowner. I’m not suggesting that the state societies get into the pro bono business, but in this case, it was the right thing to do, and hats off to JB Guyton, the NSPS and the PLSC.

—Marc Cheves, PS, Editor

Lana Shore is a land owner in Livermore, Colorado, and author of “Island Treasure—the Making and Remaking of Petit St. Vincent.”