What rights do owners of real property have in regard to the streets abutting their land? On this theme we will look at three court cases spanning a century of transportation in California. Although they rely on different legal theories, all involve the relationship between rights-of-way and private property. In these cases, the use of roads evolved to meet changing needs—at times to the dismay of the neighbors.

Venice of America

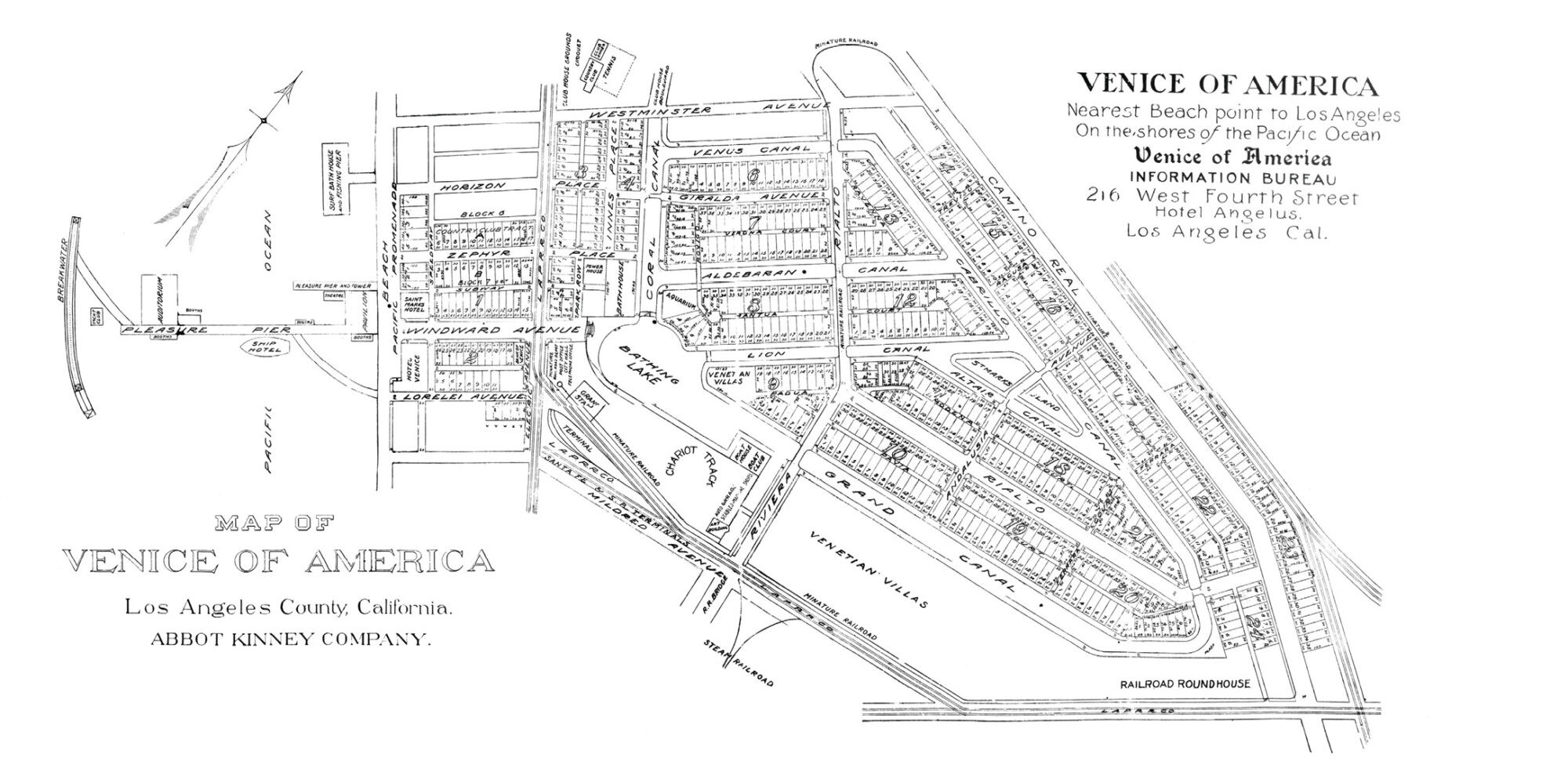

Venice is a colorful and quirky beachside community in Los Angeles that was incorporated in 1904 as a distinct city (under a prior name) (Ingersoll, 1908, p. 260). Instead of roads to access its residential lots, the Venice subdivision created a system of canals allowing ingress from the ocean. (Among the canals’ many movie appearances, Val Kilmer climbs a canal-side tree to woo Meg Ryan on the balcony of her Venice bungalow in The Doors.) Harking back to the ancient Italian seaport, this planned development was marketed as the Venice of America.

Photograph ca. 1930s of Venetian gondola riders at Lion Canal bridge, Venice, CA.

The canals were delineated as lots on the Venice tract map (e.g. Lot “J” – Altair Canal). In 1912, the developer, the Abbot Kinney Company, deeded those canal areas to the city (by then renamed Venice) on condition that they “shall be used … solely and only for permanent waterways and canals, free to the public forever.” The city maintained the canals for boating, recreation, and transportation, and, in 1925, the city of Los Angeles assumed this governmental role through annexation when Venice ceased being an independent municipality.

Detail from Official Map by Order of the Board of Supervisors of Los Angeles County, prepared by Valentine James (V.J.) Rowan, Surveyor; published by Schmidt Label & Litho. Co., 1888. Venice was established on part of the Rancho La Ballona, a Mexican land grant.

The Venice canals endure, but now you’ll find fewer of them than once existed. The loss of canals coincided with that rapid social current known as the California car culture, which gives context for the 1929 state Supreme Court case, Wattson v. Eldridge, 207 Cal. 314. The case capped a decade of rise in the number of cars in Los Angeles and corresponding drop in streetcar ridership (Elkind, 2014, p. 6).

Amid a growing demand for improved streets, the Wattson case paved the way for some of the canals to be filled in and surfaced with concrete.

The Lawsuit

Wattson arose out of a public works contract to convert the canals into streets. Even though the contractor Wattson’s construction proposal had been duly selected by the city after a public bid process, the city’s Board of Public Works refused to honor the contract award based on “serious doubt as to whether these canals constituted public streets.” (272 P. 1095 (Ct. App. 1928).) The contractor sought a writ of mandate (i.e. a court order) to compel the city to execute his contract.

Map of Venice of America, 1905, by Abbott Kinney Company.

The Court of Appeal denied the contractor’s writ petition. In light of the “unambiguous [1912] grant” (“permanent waterways”) and the subsequent conduct of both the city and those who availed themselves of the canals, the court said: “[I]t is impossible for us to reach any conclusion other than that there has been a dedication to the public for use as canals.”

As to whether the city had the power to change this use, the court was vehement that dedicated land “cannot be put to other public use inconsistent with … the original dedication.” Although it recognized the canals were certainly “watery ways of transportation,” the appeals court found that “they are chiefly used as places of amusement and recreation.” If “destroyed,” the canals “instead … would be filled with a wriggling mass of noisy and offensive smelling vehicles.”

“A Canal Is a Highway”

The California Supreme Court reversed. The Court acknowledged that the canals “must be used in conformity with the terms of the dedication,” saying, “With this rule we have no quarrel.” But by broadening the “primary object and purpose” of the dedication, the Court in Wattson reached a different conclusion than the court below had.

Los Angeles Union Station, built 1939. Art Deco, Mission/Spanish Revival styles.

Calling its interpretation “more conducive to the public good,” the Court held that the original canal dedication was “merely intended … to secure to the public generally some manner or means of ingress and egress.” Accordingly, to respond to modern demands, any new usage of the canals need only be “consistent with their character and purpose as public highways.” By this reasoning, paving over the canals “constitutes but a new adaptation of their original dedication.”

What practice pointer can be gleaned from Wattson? Lawyers often draft terms that explicitly direct how legal documents should be interpreted (a common example in contracts is: “not construed against the drafter”). With the benefit of hindsight we can see that a strict interpretation clause might have helped preserve the canals. Consider this: This dedication for boating and recreational purposes shall be construed narrowly to ensure the continued use and enjoyment of these waterways to the maximum extent possible.

The Blue Line

In the 1980s, Los Angeles embarked on a new course when it broke ground on an ambitious public transit system that would include both light rail and subway lines. The first leg to open was the Blue Line, a commuter train between L.A.’s Union Station and Long Beach (Elkind, p. 111).

Looking north on Flower Street at Los Angeles Metro Pico Station. At right, a sidewalk lies between buildings and the track.

Running through Downtown where today it passes Crypto.com Arena, the Blue Line took over portions of Flower Street. Accommodating the at-grade tracks meant losing two lanes of traffic and the street becoming one way. On the railway side of the street buildings front on a preexisting narrow sidewalk, now edged with a railing to separate pedestrians from the tracks.

In Brumer v. Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, 36 Cal.App.4th 1738 (1995), a property owner claimed this change infringed on his right to have customers drive up and park along the curb in front of his commercial building. The trial court ruled against him, and the Court of Appeal affirmed. We will first discuss the basis of the owner’s claim, followed by the court’s reasoning that led to its decision.

Right of Access

The plaintiff in Brumer alleged his property had been denied all vehicular access to Flower Street and that this was a “taking” of property under the Constitution, entitling him to compensation. (US Const. amend. V.) Although his property suffered no square footage loss—as might occur in the case of a street widening—the law recognizes a property right in the form of an “easement of access.” The court explained, “This easement consists of the right to get into the street upon which the landowners’ property abuts and from there, in a reasonable manner, to the general system of public streets” (citing the state Supreme Court in Bacich v. Bd. of Control, 23 Cal.2d 343 (1943)). Impeding such an easement could result in a taking.

Tarpey Depot, built 1892, Fresno County, California. One of three depots that dotted the San Joaquin Valley Railroad. This extant building was relocated to 399 Clovis Avenue.

However, not every interference with access to the street amounts to a taking. To prevail in such a claim, the owner must demonstrate “a substantial impairment of his right of access to the general system of public streets.” Satisfying this legal standard requires a fact-based inquiry.

The court discussed a continuum of impairment of access cases. At one extreme are mere traffic regulations, such as “placing permanent dividing strips which deprive an abutter of direct access to the opposite side of the highway, painting double white lines on the highway, or designating the entire street as a one-way street.”

These examples are plainly within a city’s police power and invoke no constitutional right to compensation, even though they “may impede the convenience [of driving], and may necessitate circuity of travel.” The court said that any resulting “loss of business or of value of the property … is simply a risk the property owner assumes when he lives in modern society.”

At the other extreme, courts have found substantial impairment of access to properties where, for example, the city built a raised viaduct on the abutting road (Goycoolea v. City of Los Angeles) and where reaching a property was effectively “cut off by [a freeway] off-ramp and … nine-inch-high concrete divider” (Blumenstein v. City of Long Beach).

No Actionable Taking

The characteristics of the property in Brumer worked against the owner’s claim. The lot was situated at the corner of Flower Street and Venice Boulevard (an east-west thoroughfare that leads to Venice Beach). In fact, the property’s ample Venice frontage (150 feet) was three times the distance along Flower.

In addition, at the rear was an alley, which, as with the Venice Boulevard property line, the railway left untouched. Having public roads on three sides—and no effect on pedestrian access—lessened the proportional impact of the Blue Line on the property overall.

The court concluded that any interference with access in Brumer was not substantial. It reasoned that “the net effect on vehicular access to plaintiffs’ property is no different than if the city had simply exercised its police power to prohibit all street parking on Flower Street.”

Brumer teaches that although landowners enjoy a right of access, the standard to prove a taking of that right is a high one. It is a truism that things change, as in the city’s pursuit of public transit. It follows that an abutting owner “cannot demand that the adjacent street be left in its original condition for all time.”

Rails to Trails

Our final case involves not a public road but a right-of-way easement held by Southern Pacific Railroad. (Toews v. United States, 376 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2004).) In Toews, when the government authorized an interim use of the easement for hiking and biking under the federal rails-to-trails law, landowners claimed a right to compensation under the Fifth Amendment because such uses were beyond the scope of the easement encumbering their lands. The trial court agreed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed.

Weber Creek Bridge, built 1903 for Placerville & Lake Tahoe Railway, and now part of the El Dorado County, California rail trail.

The segment of track in Toews that the railroad ceased operating was its Clovis Branch, which had transported freight in Fresno County, California, for a century. Southern Pacific and the city of Clovis entered into an agreement which allowed the city to develop the right-of-way with pedestrian, equestrian, and bike paths “in the near term,” while contemplating “light rail or other transit modes” in the future.

Congress enacted the National Trails System Act in response to a sharp decline in the use of trains in the last century and national security concerns over the correlated abandonment of railroad property (because once the country’s freight rail network is gone, it’s gone). (16 U.S.C. § 1241 et seq.; Ferster, 2006.) The law was designed “to preserve for possible future railroad use rights-of-way not currently in service and to allow interim use of the land as recreational trails.” (Preseault v. I.C.C., 494 U.S. 1 (1990); see Wendy Lathrop’s column on rails-to-trails in TAS, July/Aug. 2004.) Los Angeles is a case in point for disused rail lines experiencing a resurgence: the Blue Line follows the historic corridor of the city’s defunct early twentieth-century streetcar system (Elkind, p. 109).

Fee or Easement

In Toews, the original 1891 deed granted a “Right of Way for [the grantee’s] proposed Railroad over [land] owned by me … and for its tracks, turntables, depots, water tanks and other appurtenances.”

Analysis of a right-of-way begins with the nature of the right and the scope of the authorized use. Right-of-way is an ambiguous term in that it doesn’t distinguish between a fee simple estate (complete ownership) or a lesser interest in an easement (the right to use another’s land). In both cases, the term describes the right “to pass over land” or, generally speaking, the strip of land itself. (Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed.).)

The court in Toews discussed the presence of this ambiguity in another railroad case, Preseault v. U.S., in which an 1899 conveyance “was obscure” and left “real doubt [as to] what was conveyed and what did it mean.” But in Toews, no such doubt existed. The court said, “The terms of the deed … are explicit, [and the] trial court properly found the grant to constitute an easement.”

Shifting Use Doctrine

Since the railroad right-of-way was a mere easement, the “defining issue” of the case was its scope. As with the canal dedication in Wattson v. Eldridge, the permitted uses of an easement are limited by the grant. The court in Toews said: “It is elementary law that if the Government … authorizes the use of … an existing railroad easement for purposes and in a manner not allowed by the terms of the grant of the easement, the Government has taken the landowner’s property for the new use.”

To argue that the railroad easement did embrace the trail use, the government “heavily cited and relied upon” Wattson to illustrate the “shifting use doctrine.” Under this concept, which in Wattson had enabled a canal to be turned into a paved street, the court relayed the government’s position “that a railroad’s use of an easement may transmogrify into the public’s use as a recreational trail.”

Although the court in Toews accepted the holding in Wattson, it reasoned that here the uses of the easement (for a railroad or a trail) were too dissimilar. The court held that an “easement defined as one for railroad purposes is not stretchable into an easement for a … trail and linear park for skateboarders and picnickers, however desirable such uses may be.” The court said the government has the power to create such parks, “[b]ut the private property interests taken are not free”; they require just compensation.

The Future

We have read about dedications, access, and easements. In addition to each case focusing on a particular use of right-of-way, the thread running through them all is that things change. In its explanation of the shifting use doctrine, the court in Toews couldn’t resist the idiom that the lot owners in Wattson, who had hitherto sailed skiffs to their Venice homes, “were left high and dry.”

Of course it is uncertain how the use of transportation corridors might change in the future. When change occurs, the legal issues discussed here may come into play. In considering the possibility of rail service returning to Clovis in “the distant future,” the court in Toews was expressive: It will depend on “economic and social change, and a change in government policy by managers not yet known or perhaps even born.”

Bibliography

Ethan N. Elkind, Railtown: The Fight for the Los Angeles Metro Rail and the Future of the City (Univ. of California Press, 2014).

Andrea Ferster, “Rails-to-Trails Conversions: A Review of Legal Issues,” Planning and Environmental Law, Vol. 58, No. 9 (American Planning Association, 2006).