When the mayor of New York City, in 1810, took a pencil and drew a proposed canal route on a piece of paper connecting the Hudson River with Lake Erie, everyone thought he was crazy. In fact, Thomas Jefferson already said it was “a little short of madness.” De Witt Clinton would not back down though and when the Erie Canal was completed in 1825, and he was now the Governor of the State of New York, it was everything but a “Folly”. Nicknamed Clinton’s Ditch, the Erie Canal has been in continuous operation ever since and made New York City the busiest port in the Country within 15 years of the opening of the Canal. In fact, it changed the Empire State altogether as today “nearly 80% of upstate New York’s population lives within 25 miles of the Erie Canal”.1

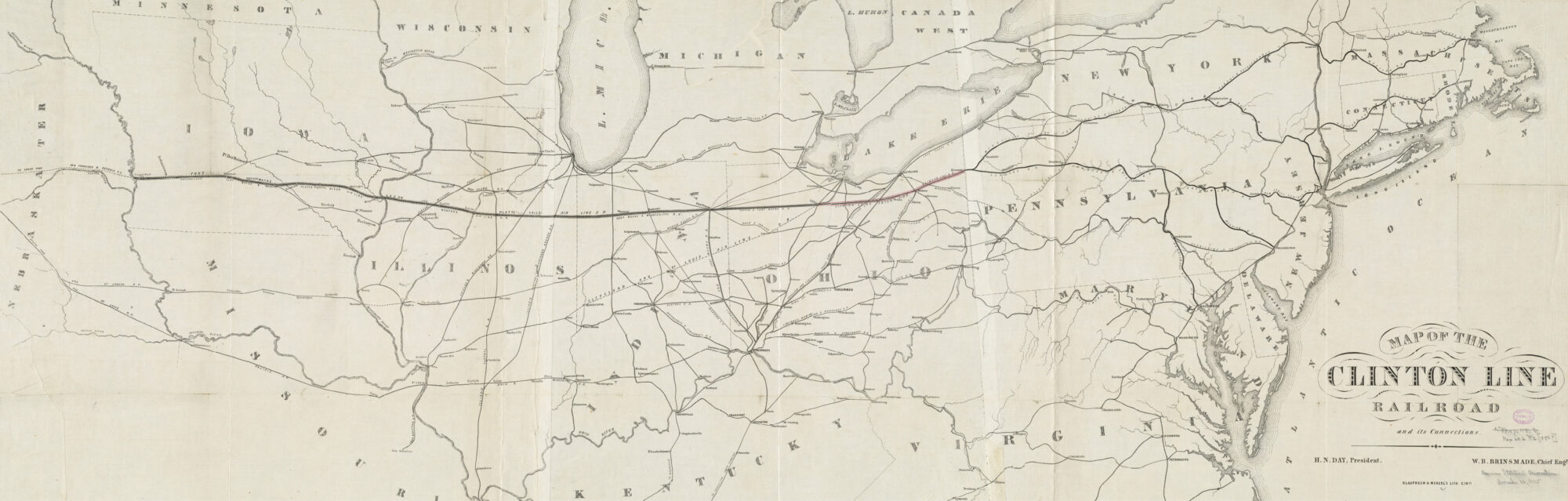

“Map of the Clinton Line Railroad and its connections.” Map. Cincinnati: Klauprech & Menzel, [1850–1859]. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center. https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:cj82kn75h (accessed March 17, 2024).

Clinton Railroad Roman Arch Bridge near downtown Hudson, Ohio. Photo courtesy of the author.

The goal from the beginning was to branch East and West, in a straight line, and slice across the highest points along the route. This would create a railroad with very large radii, if any, and keep the grade of the railroad to a minimum. Survey crews were sent out in October of 1852 searching for the best route East to Pennsylvania. Over 600 miles were surveyed, extending as far as 75 miles into Pennsylvania, before a preferred route was chosen. This route, East from Hudson, then Northeast through Kinsman, would eventually connect to the New York and Erie Railroad through Meadville, Pennsylvania. Once the route was selected, the right of way was voluntarily donated and secured. The construction consisted of removing 18 inches of topsoil and replacing it with ballast stone from a quarry 12 miles East of Hudson. The bridges and culverts were started all being along a precisely laid out alignment where 85 percent of the 55.3 miles were straight and where a maximum grade did not exceed 39.6 feet per mile. The work on the Railroad East from Hudson, through Aurora, Mantua and into Kinsman was nearly complete when financial disaster hit, and all work was stopped. Although the railroad ties were delivered, not a single piece of iron rail was laid. Only the initial grading and infrastructure happened, most of which can still be seen today, that is if you know where to look.

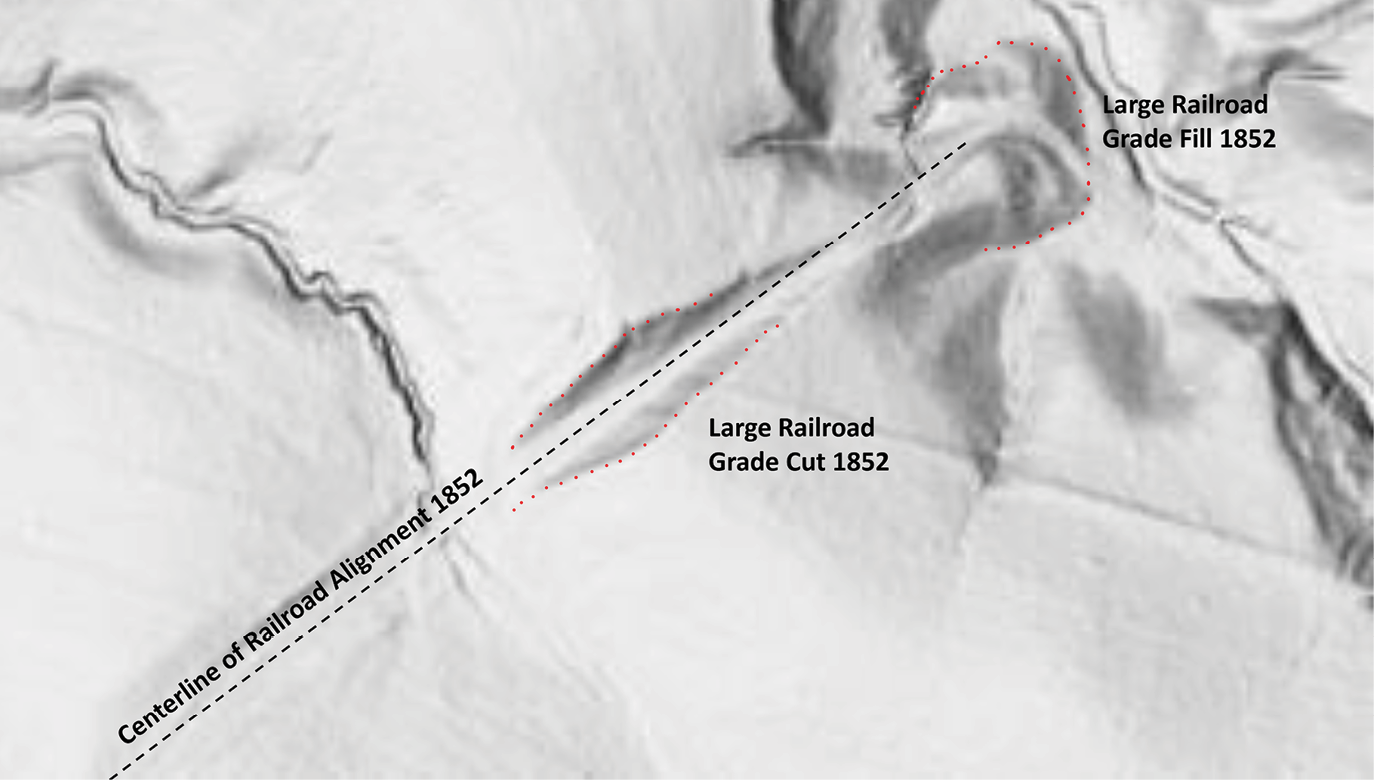

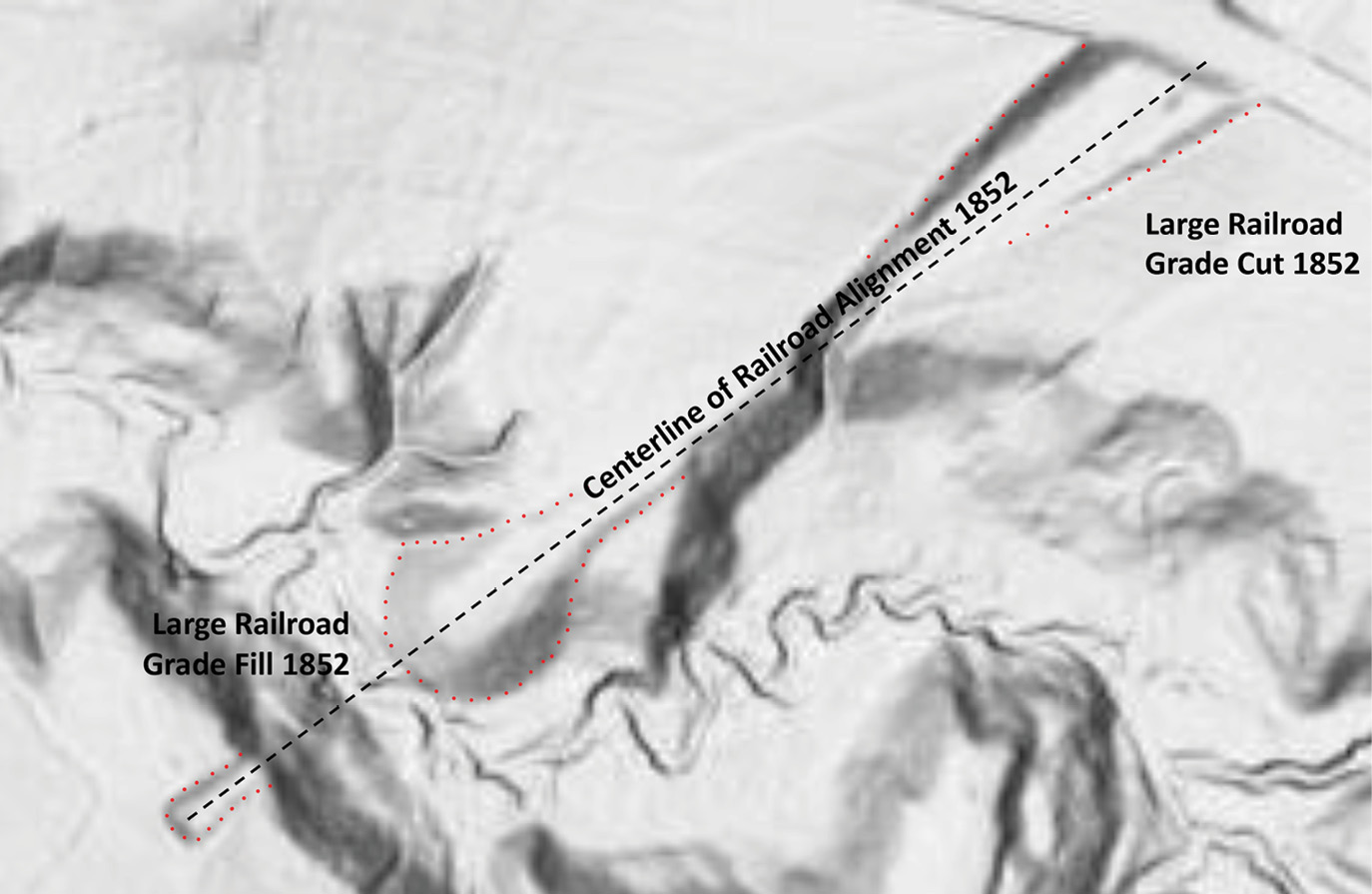

3DEP classified Lidar data with Multidirectional Hillshade showing hidden railroad bed from 1852. Courtesy of the author.

The same story goes for the Clinton Line Extension Railroad. Also centered in Hudson, this Railroad also had many routes surveyed, starting in July of 1853. Excitement of the potential benefits of the railroad brought politics into play, but the railroad leaders trusted their surveyors with the best, and most cost-effective path. This eliminated a route through Peninsula and Cuyahoga Falls and gave way for one southwest from Hudson, across the Cuyahoga Valley, North of Medina, and straight West to Tiffin where it would connect to the Tiffin and Fort Wayne Railroad. The route for the Clinton Line Extension would have been simple if it wouldn’t had been for the Cuyahoga Valley and all of its streams and contours. Multiple route surveys were made in and across the valley during 1853 and 1854 by Hosea Paul and his two sons. Hosea was the Summit County, Ohio surveyor from 1857-1870. After his death his son, Robert took over as County surveyor. The family ties ran deep as other family members became other notable public officials. The records of the Paul Brothers are now housed in 85 containers at the Western Reserve Historical Society somewhere hiding the handwritten field notes of the Valley routes. The chosen route was the one with the straightest path and the gentlest slope. The route between Hudson and Tiffin was measured at 93.84 miles and 87 percent of the proposed route was straight. The maximum grade was also 39.6 feet per mile with the exception of the valley where it maxed out at 43.88 feet per mile. For decades this mysterious and lost route was thought to be near the big oxbow along Salt Run off Truxell Road. A curious mound was discovered there around 1965 and thought to be the spot. Further studies were recently done however, revealing the true route, and bringing in advanced technologies to prove the theory.

During the work of his final thesis project at Summit Metro Parks Deep Lock Quarry, the author discovered a topographical anomaly using aerial lidar (light detection and ranging) data. An old, abandoned railroad popped out on his map after creating a multidirectional hillshade with GIS software. The author then had an idea to use the same process to trace the route of the Clinton Line Extension Railroad in the National Park. Fenicle, residing in Hudson, studied the 1856 map of Summit County, ironically put together by Hosea Paul and showing the approximate route of the railroad. His curiosity grew as he field visited the multiple 1852 Roman arch bridges still in existence in and around Hudson, as well as clearly visible raised railroad beds and bridge abutments. The arch bridges were designed and built for two sets of tracks, although the railbed was built for a single track with design constraints of 20.5 feet wide beds with 15-foot embankments. The author focused inside the National Park in Boston Township Lot 27 near the intersection of the railroad and the current Quick Road. It is interesting to note that nearby lot 25, 31 and 33 were absorbed by the railroad as it was common to buy entire farms before the alignment was determined and then use them for investments if they were not chosen. Using his decades of surveying and engineering expertise, Fenicle quickly identified the original route laid out by surveyor Hosea Paul in 1853. To the naked eye there is almost nothing to be seen, however, remove all the trees and vegetation from the surveyed area and the construction of the railroad bed jumps out like a sore thumb.

Various 3DEP classified Lidar data with Multidirectional Hillshade showing hidden railroad bed from 1852 in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Courtesy of the author.

Technically called classification, the author utilized the last return of aerial lidar data from the National 3D Elevation Program. He imported millions of remotely sensed lidar data points, classified them, and created a bare earth three-dimensional model. The data was collected in 2019 as part of a nationwide collaboration of various agencies like the United States Geological Survey and the Federal Emergency Management Agency to name a few. The data is light waves sent out by a sensor mounted in a manned aircraft flying at a speed of 175 mph at an altitude of 7000 feet. The vertical accuracy in the National Park is around 4 inches. The findings, when viewed, are nothing short of amazing. Fenicle and National Park archeologist Grant Day walked the route one wet fall day in 2023. Day was fascinated that this topographical anomaly existed this whole time with no one noticing for well over a century. Local hikers may recognize the flatness of the ancient railroad bed as they hike a very straight portion of the Cross Country Trail in the Kendall Lake Area. With the trained eye you can look to both sides and see the engineered cut and almost hear the whistle of the train that never went by.

Clinton Railroad Sandstone Bridge Abutment along the banks of Tinker Creek Northeast of Hudson, Ohio. Photo courtesy of the author.

Sidebar

Clinton Air Line Railroad

- Clinton Line Railroad (Hudson to Pennsylvania State Line) Clinton Line Extension Railroad (Hudson to Tiffin, Ohio) Hudson and Painesville Railroad (Hudson to Lake Erie)

- Entire Route—Atlantic Ocean to Missouri River (Proposed)

- Designed by DeWitt Clinton Jr., son of former New York Governor and builder of Erie Canal, DeWitt Clinton

- Headquartered in Hudson, Ohio

- President Henry Noble Day (former Professor at Western Reserve College)

- $200,000 was raised in 1852 mostly from Hudsonites.

- Exited Ohio Northeast of Kinsman in Trumball County.

- Airline railroad was one that maintained a straight line

- Parcels acquired in 1853-1854

Sources

collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:cj82kn75h

“Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library”

loc.gov/resource/g4083s.la000679a/?r=0.52,0.53,0.18,0.114,0

“Map of Summit Co., Ohio”

tribtoday.com/news/local-news/2023/09/the-railway-that-never-was-tracked-through- kinsman/

trumbullcountyhistory.com/clinton-air-line/

railroadforums.com/forum/index.php?threads/clinton-airline-railroad-ohio-1950s.12234/

record-courier.com/story/lifestyle/2022/02/09/when-trains-whistled-their-way-through- aurora-historical-society-john-kudley/6669609001/

ead.ohiolink.edu/xtf-ead/view?docId=ead/OCLWHi0690.xml;query=;brand=default

usgs.gov/3d-elevation-program/what-3dep