The Rio Bravo del Norte, or the Rio Grande, meanders its way from Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico. The Great River of the North historically would flow uninterrupted to the Gulf of Mexico, but now the water from Colorado is lucky to make it there. The Big River, as it is also known, is the border between multiple Mexican States and even our International Border between Texas and Mexico. For a mere 25 miles though The Rio Grande is so much more. It is the border between Texas and New Mexico by El Paso. Laying between the International Boundary, being 31 degrees and 47 minutes North Latitude, and the North line of Texas, being 32 degrees North Latitude, this short snaking section of the Rio Grande lead to so much contention that it landed in the Supreme Court. Once again, Samuel Stinson Gannett was called upon to not only resolve its location, but to resolve its location as it existed on September 9th, 1850.

The history of this short segment of the Rio Grande is vast dating back to 1595 with the colonization of New Mexico by Don Juan de Onate. Technically though, our history starts when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2nd, 1848, putting an end to the Mexican-American War. The treaty defined the international boundary, 25 miles of it being the disputed section eventually becoming the dividing line between Texas and New Mexico. Once the treaty was signed a commission was assigned by both Countries to survey the common line. As always, the map used for the treaty was in error and the international border geographically fell about 32 miles North of where depicted on the map. The map used in the treaty was drawn by John Disturnell and later partially copied by General Land Office principal draftsman Ephraim Gilman in 1848. Both maps had distortions in West Texas along the Rio Grande eventually leading to more arguments and the eventual disbanding of the commission all together in 1852. The Gadsden Treaty of 1853 solved this problem and made room for the proposed Southern route of the Transcontinental Railroad. This fixed the international border at this section at 31 degrees and 47 minutes North Latitude. Prior to that though two main surveys were made on opposite sides of the Rio Grande. On the East side a survey was made by Charles Radziminski. Radziminski has a very colorful history as he came to American in 1834 as a Polish Revolutionary exile. He climbed the ranks of the United States Topographical Engineers eventually landing the role as the Secretary of the United States Boundary Commission. His name is amongst significant others on a piece of paper stuffed in a glass bottle buried five feet below the monument marking the initial point of the joint survey between the United States and Mexico. The other survey, on the West side, was made by Jose Salazar y Larregui and Agustin y Luis Diaz—titled the Salazar—Diaz Survey of 1852. This was a highly accurate and detailed survey for its day. Salazar was extremely talented and held the titles of astronomer, mineralogist and geographer. Diaz, on the other hand, climbed the ranks of the Mexican Corps of Engineers eventually taking charge of Mexico’s Geographic Exploration Commission.

Texas became the 28th State on December 29, 1845. A dispute arose between Texas and the United States and the area trying to become the New Mexico Territory. It wasn’t until President Millard Fillmore stepped in and convinced Congress to pass the Texas Boundary Act as approved by the President on September 9th, 1850. The Act defined the boundaries of Texas as “…thence on the said parallel of thirty two degrees of North Latitude to the Rio Bravo del Norte, and thence with the channel of said river to the Gulf of Mexico”. This Act, and description, created the Territory of New Mexico which eventually became the 47th State on January 6th, 1912. The State Constitution stated “…thence along the 32nd parallel to the Rio Grande, also known as the Rio Bravo del Norte, as it existed on the 9th day of September, 1850; thence following the main channel of said river, as it existed on the 9th day of September, 1850, to the parallel of 31 degree 47 minutes North Latitude”. Prior to becoming a State though, New Mexico had to agree to a joint resolution recognizing the survey done by John H. Clark of the 32nd parallel of Latitude.

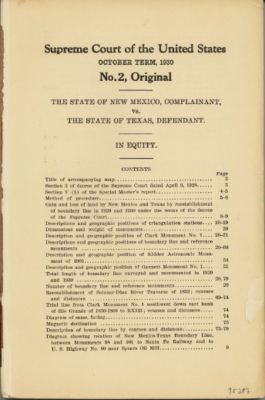

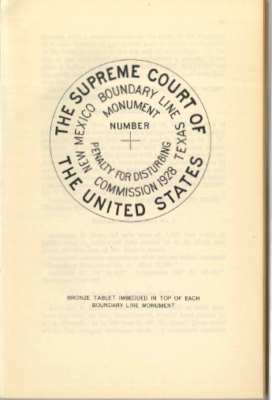

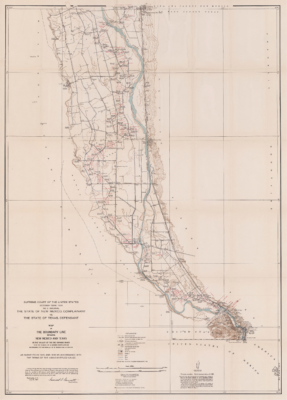

Sample page selections from the rare 1930 Supreme Court Document highlighting the survey report by Gannett. Courtesy of Dartmouth College & Texas General Land Office

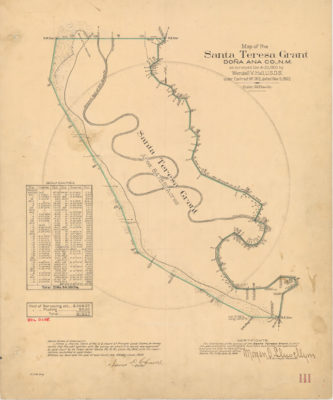

It wasn’t until United States Deputy Surveyor Wendell Hall surveyed the Santa Teresa Grant that it was realized that no one really knew where the Rio Grande existed on September 9, 1850. The survey by Hall placed approximately 2,700 acres in what was thought to be Texas. New Mexico filed suit with the United States Supreme Court on January 31, 1913 asking for a determination where the Rio Grande was on September 9th, 1850. Well known Boston Attorney and author Charles Warren was assigned the position of Special Master. After hearing testimony for a matter of years and after researching and reviewing all pertinent maps the Special Master made his report. In Volume V (1) of his report Special Master Charles Warren states that the Rio Grande as it existed on September 9th, 1850 shall be determined by retracing the John H. Clark Survey and the Salazar – Diaz Survey of 1852. The Special Master could not find copies of the Radziminski Survey so it was dismissed as evidence. Furthermore, against the suggestion by Special Master, the Supreme Court rejected any claim of the position of the Rio Grande by accretion or avulsion. The location of the Rio Grande had to be laid on the ground as it existing on September 9th, 1850 and it was then called upon to have Samuel Stinson Gannett do the job.

It wasn’t until United States Deputy Surveyor Wendell Hall surveyed the Santa Teresa Grant that it was realized that no one really knew where the Rio Grande existed on September 9, 1850. The survey by Hall placed approximately 2,700 acres in what was thought to be Texas. New Mexico filed suit with the United States Supreme Court on January 31, 1913 asking for a determination where the Rio Grande was on September 9th, 1850. Well known Boston Attorney and author Charles Warren was assigned the position of Special Master. After hearing testimony for a matter of years and after researching and reviewing all pertinent maps the Special Master made his report. In Volume V (1) of his report Special Master Charles Warren states that the Rio Grande as it existed on September 9th, 1850 shall be determined by retracing the John H. Clark Survey and the Salazar – Diaz Survey of 1852. The Special Master could not find copies of the Radziminski Survey so it was dismissed as evidence. Furthermore, against the suggestion by Special Master, the Supreme Court rejected any claim of the position of the Rio Grande by accretion or avulsion. The location of the Rio Grande had to be laid on the ground as it existing on September 9th, 1850 and it was then called upon to have Samuel Stinson Gannett do the job.

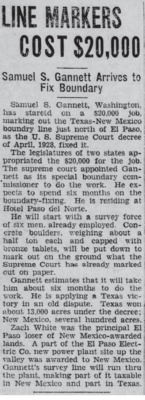

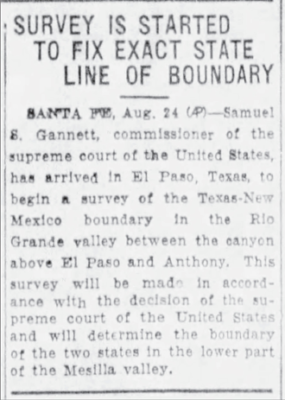

Gannett studied the triangulation notes from both the Clark Survey and the Salazar – Diaz Survey. He started his field work in August of 1929 and it lasted until February of 1930. Gannett and crew first laid out a traverse through the entire valley of the disputed territory. They then tied in the “control monuments” as used in the Salazar – Diaz Survey of 1852. These “control monuments” from 1852 were simply natural objects like high bluffs or “… a well known mountain with a definite sharp summit…” With this they were able to reproduce the triangulation network and prove other known geographic location as used by Salazar and Diaz. The could then calculate where the West bank of the Rio Grande was and then offset it by 150 feet to the East for the centerline. Locations were then chosen for permanent monuments at each angle point, now lying on dry land. In the end 105 concrete monuments were set along 25.17 miles. There were also 45 reference monuments set and 6 permanent triangulation stations established. In the final report to the Supreme Court, Gannett wrote “…may therefore be considered as located within a few feet of the original Salazar-Diaz stations and serve as a check…” Obviously his triangulation work was much tighter as angles were measured four times at each monument along the line. Polaris was also observed every three miles. The distances were measured with a 300 foot steel tape and checked to a 300 foot invar tape every other day. Similar to the monuments set a few years earlier, on the other side of the State, marking the 100th Meridian they were in the shape of a conical frustum 36” long, 8” at the top and 14” at the base. Once again the concrete was molded in galvanized metal and placed on a concrete foundation. A bronze inscribed tablet was then placed on top of the concrete monument. Also similar to the 100th Meridian between Texas and Oklahoma a majority of the field work was completed by Samuel’s close friend Eugene L. McNair. McNair had a most impressive career with the United States Geological Survey and was called upon to assist Gannett in multiple high order surveys for the Supreme Court. In September of 1934 while assisting Gannett on the New Hampshire – Vermont state line for the Supreme Court, McNair suddenly passed away at the age of 71.

Gannett studied the triangulation notes from both the Clark Survey and the Salazar – Diaz Survey. He started his field work in August of 1929 and it lasted until February of 1930. Gannett and crew first laid out a traverse through the entire valley of the disputed territory. They then tied in the “control monuments” as used in the Salazar – Diaz Survey of 1852. These “control monuments” from 1852 were simply natural objects like high bluffs or “… a well known mountain with a definite sharp summit…” With this they were able to reproduce the triangulation network and prove other known geographic location as used by Salazar and Diaz. The could then calculate where the West bank of the Rio Grande was and then offset it by 150 feet to the East for the centerline. Locations were then chosen for permanent monuments at each angle point, now lying on dry land. In the end 105 concrete monuments were set along 25.17 miles. There were also 45 reference monuments set and 6 permanent triangulation stations established. In the final report to the Supreme Court, Gannett wrote “…may therefore be considered as located within a few feet of the original Salazar-Diaz stations and serve as a check…” Obviously his triangulation work was much tighter as angles were measured four times at each monument along the line. Polaris was also observed every three miles. The distances were measured with a 300 foot steel tape and checked to a 300 foot invar tape every other day. Similar to the monuments set a few years earlier, on the other side of the State, marking the 100th Meridian they were in the shape of a conical frustum 36” long, 8” at the top and 14” at the base. Once again the concrete was molded in galvanized metal and placed on a concrete foundation. A bronze inscribed tablet was then placed on top of the concrete monument. Also similar to the 100th Meridian between Texas and Oklahoma a majority of the field work was completed by Samuel’s close friend Eugene L. McNair. McNair had a most impressive career with the United States Geological Survey and was called upon to assist Gannett in multiple high order surveys for the Supreme Court. In September of 1934 while assisting Gannett on the New Hampshire – Vermont state line for the Supreme Court, McNair suddenly passed away at the age of 71.

Once complete, Samuel Stinson Gannet presented his report to the United Stated Supreme Court. This well put together report details the history of the dispute and the instructions by which he did his survey. In detail, Gannett describes his work and the instruments used. He lists each monument, and references, with true bearing and distances to others for future retracement. He also created a highly detailed map of the entire line with contours. This report by Gannett was given to the United States Supreme Court on July 17, 1930 and was quickly approved settling yet another highly disputed line between two adjoining States. And although it may not make sense today, the Rio Grande has been permanently monumented as it was on September 9th, 1850.

Note: Special thanks to Kery Greiner, Steve Cobb & Dr. Kurt Wurm and all those who volunteered on the 2005-2006 retracement by the Southern Rio Grande Chapter of the New Mexico Professional Surveyors and the Paso Del Norte Chapter of the Texas Society of Professional Surveyors.