This saga begins in Trinity County, California where Steven A.D. Puter (pronounced “pewter”) was born in January 1857. Two years later, his father moved the family to a homestead claim on the Mad River in Humboldt County, which was about 20 miles north of Eureka. He was reared on this property until 1888 when he moved to Portland, Oregon until 1902, when he then moved his family to Berkeley, California.

Fig. 1. This kind of timber land acquired fraudulently by C. A. Smith through Puter and McKinley, liable to be cancelled by the Government. This photograph was taken in March, 1908, and represents Puter in “cruiser” costume estimating the timber on NW 1/4, Sec. 20 Tp. 14 S., R. 3 E. (Linn County, Or.) portions of which ran 300,000 feet to the acre. The entire quarter section aggregated 20,000,000 feet, and was the claim filed on personally by Puter in 1900.

Puter’s first experience with the public domain was in the summer of 1875 when he was hired as an axman for a Deputy Surveyor named Forman, who had a contract to subdivide several townships of timber land near his family’s homestead. As he explains; “I became so proficient in my duties that after blazing the lines and marking the witness trees for a few months, I was placed in charge of a crew and manipulated the compass.”

As soon as the survey had been approved by the Surveyor-General, there was a rush for “timber claims.” Since he had surveyed the township he said “by reason of my field work on the survey, I gained a knowledge of all the desirable claims in the tract, and located a number of applicants, charging them $25 each, at the same time taking a contract to build them a cabin on their claims for $25 additional. The cabins so constructed consisted of a shack made out of shakes or split boards from the timber on the claims, the size of each cabin 12 by 16 feet and 7 feet high, one window, board floor and wooden fireplace… the building of the cabin being the only improvement made on a pre-emption or homestead claim in those days. The entrymen hardly ever slept over night there, although they made final proof within 8 or 10 months from the date of filing, wherein they alleged a continuous residence”.

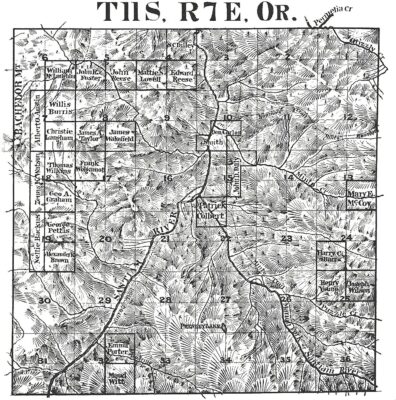

Fig. 2

Puter goes on to say, “I negotiated the sale of this tract to a Eureka capitalist for sums ranging from $800 to $1200 per claim”. “Later the purchaser sold to the California Redwood Company for $25 per acre. The latter corporation transferred the tract to the Humboldt Mill & Lumber Company, which erected sawmills and commenced the manufacture of the timber into merchantable lumber. At the present time, the timber on these lands possesses an intrinsic value of from $200 to $300 per acre.”

“The first big fraud under the Timber and Stone Act of June 3, 1878, that ever occurred on the Pacific Coast was consummated in Humbolt County, California, during 1882-83. As soon as the land was surveyed and thrown open to entry, the California Redwood Company, with offices in Eureka, began to hire men to file on the entire tract under the Timber and Stone act referred to. At that time, the people desiring to avail themselves of its provisions were not required to make a personal examination of the portions they wished to file on, nor were they obliged to go to the land office to make final proof.

Fig. 3

All that was necessary in this connection was for the entryman to appear at the land office at the time of making the filing, exhibit his first papers to show that he was either a citizen of the United States, or had declared his intention to become such…and his entry would be allowed… Under these conditions, the company was enabled to run men into the land office by the hundreds… I have known agents of the company to take at one time to take as many of twenty-five men from “Coffee Jacks” sailor boarding house in Eureka to the county court house, where they would take out their first papers, declare their intention to become citizens of the United States, after which they would proceed direct to the land office and make their filings, all the location papers having been made out. Then they would appear before Fred W. Bell, a notary public, and execute an acknowledgement of a blank deed, receive the stipulated price of $50, and return to their ships or to the boarding house from whence they came.”

In 1888, Puter “decided to seek fresher pastures in Oregon. Upon my arrival in the new field, I found the land business booming, every hotel in the timbered section of the state being crowded with timber land speculators, cruisers, (see Figure 1) and locaters. I went into the locating business the first thing and continued to do a land office business for two years.) This was in 1889 and 1890, and during all this time, the woods were fairly alive with timber men. My early years in California enabled me to grasp conditions quite readily and become acquainted with the most desirable tracts in short order; consequently, I soon got into the swim.

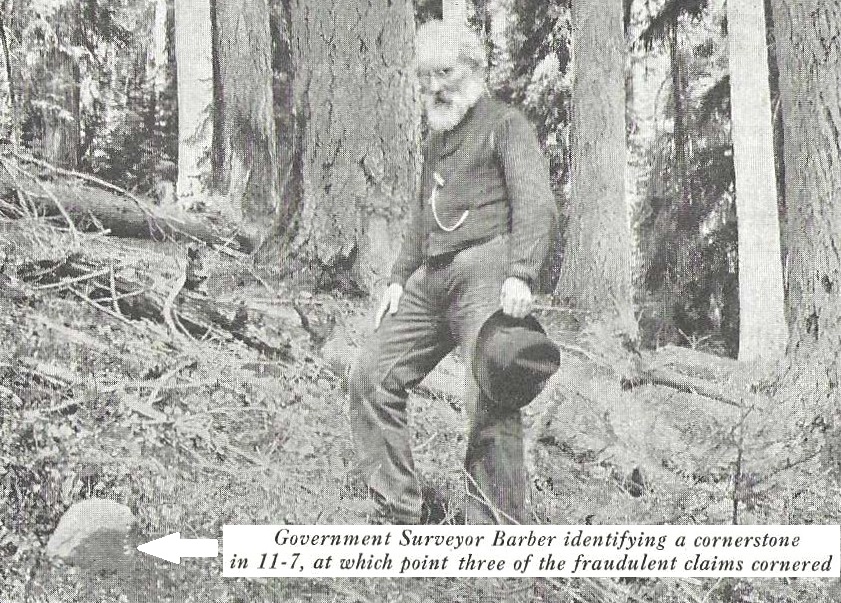

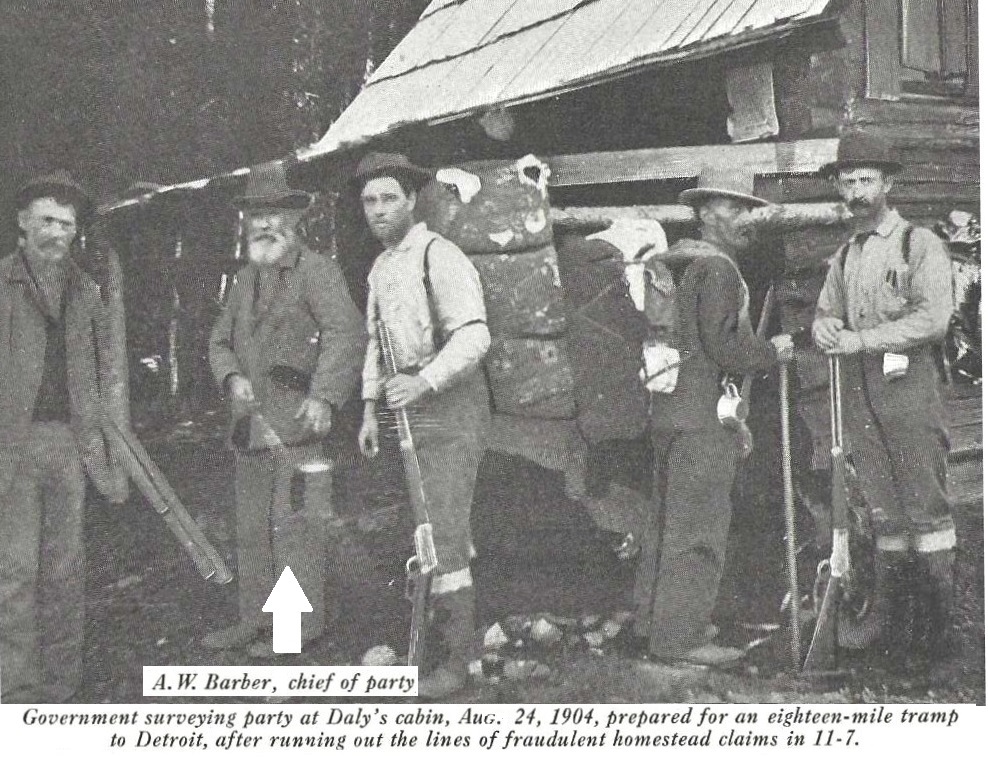

Fig. 4. Government Surveyor Barber identifying a cornerstone in 11-7, at which point three of the fraudulent claims cornered.

Moneyed men were here from Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and other Middle West states, eager to make investments and grasp the unlimited opportunities offered of reaping big returns, and as a result, thousands of men were sent into the forests of Tillamook and Clatsop Counties, Oregon, as well as throughout various sections of Washington, to file on timber claims, and in nearly every instance, the entrymen had contracted in advance to transfer their titles to some lumber company, or syndicate of Eastern capitalists”.

The Timber and Stone Act of June 3, 1878, was the favorite method of acquiring title at that time….titles could be rushed through much quicker than by the pre-emption or homestead laws. The increasing demand for patents at the Oregon City Land Office also aroused the suspicion of the officials at Washington D.C. and special agents were sent into the field for the purpose of making investigations….but there were few actual cancelations, the special agents, as usual, were standing in with the land grabbers. Thousands upon thousands of acres including the cream of timber claims in the states of Oregon and Washington were being secured by eastern lumbermen and capitalists, the majority of whom came from Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota and nearly all of the claims were fraudulently obtained.

Fig. 5

The special agents sent out by the government were picked up as they appeared on the scene, with the capitalists and locators standing hand in hand. It was an easy matter and with the aid of these agents, baffled the government in its attempt to secure evidence. “During 1899 and 1900, my partner, Horace G. McKinley, and myself had been doing considerable speculating in timber lands in Oregon…and had occasion to visit frequently the Roseburg and Oregon City Land Offices. It came to our notice that a great many unperfected homestead entries within the Cascade Forest Reserve were being proven up on…these tracts, immediately after final proofs were made, were being transferred to lumber syndicates, for the purpose of creating ‘base’ to be used in selecting other lands in lieu thereof.

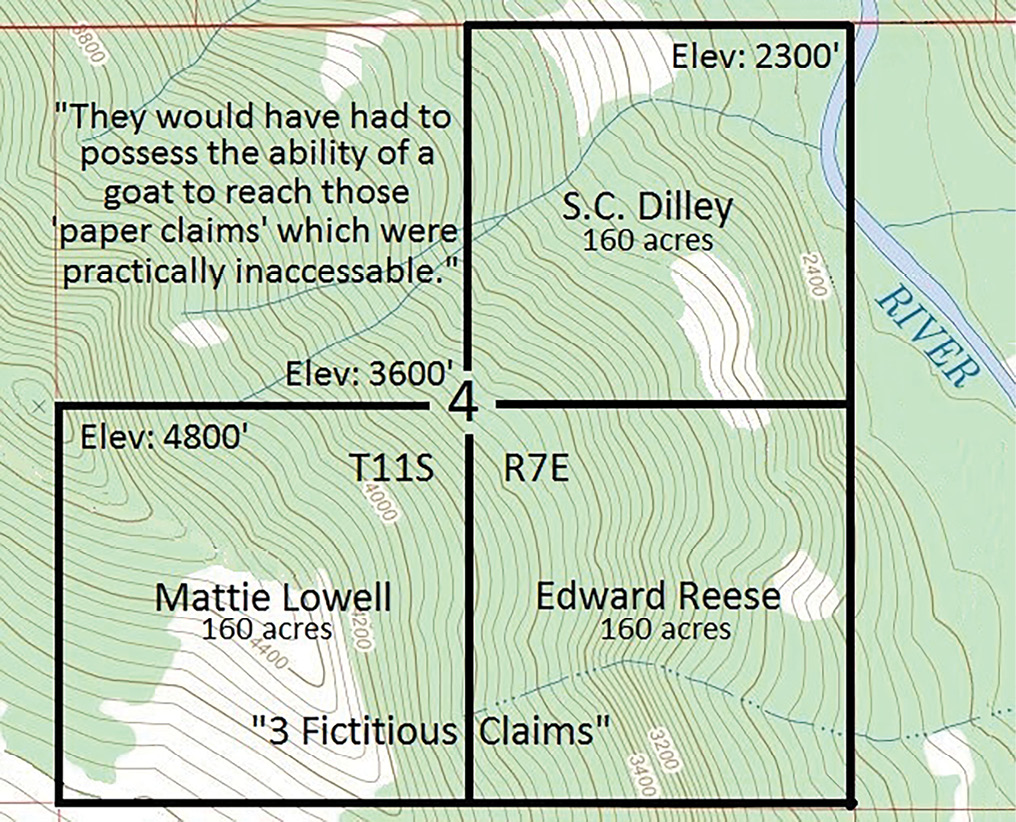

During 1900, the survey of Township 11 South, Range 7 East, Willamette Meridian, was approved and the lands therein were opened to entry. When McKinley and I learned that Township 11-7 was in the market, and realizing that it was situated near the summit of the Cascade Mountains, at an elevation where the prospects of Governmental inquiry concerning entries were exceedingly remote, we concluded to make a lot of homestead filings there, under the pretense that it was being done by settlers who had long been residents of the township, and who were about to take advantage of the law that permitted settlers in a newly surveyed township to initiate their titles within ninety days after approval of the survey. (see Figure 2 at the top of page 1)

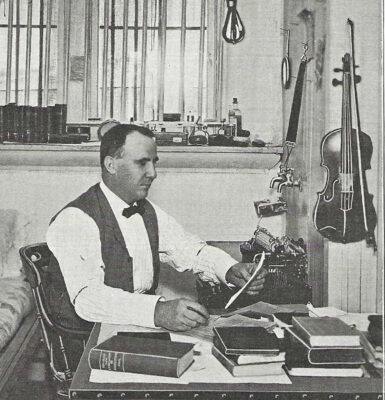

Fig. 6. Steven A.D. Puter at work in his cell at the Rocky Butte Jail in Portland, OR, preparing the manuscript for “Looters” in 1907.

However, the term of a person’s residence on the claim before survey counts as part of the five-year period required for actual presence under the homestead law. If a person has been in residence on a tract of land for the full 5 years, it only becomes necessary for him to make his filing, advertise during a period of six weeks, submit his final proofs and receive his final certificate…which is followed by a patent…for no other expense than the advertising and filing fees, which would amount to no more than $25.

Our idea was to locate as many persons as possible in that township [these being fictional “persons”] under the homestead law, and to furnish them the money with which to make final proof and cover their incidental expenses, and as soon as final proof was made, to have them deed the land to us at a price agreed upon in advance. We associated with us in the venture, Dan W. Tarpley, a young attorney and notary public of Salem, Oregon, agreeing to pay him a certain percentage of the commissions as soon as we procured titles and disposed of the “claims.” (see Figure 3)

His services, in return, were to conduct the “homesteaders” to the land office for the purpose of filing their claims, attending to the advertising, and making the final proofs. All together, we located 12 claims of 160 acres each. A few weeks after final proofs were made, while McKinley and I were at a hotel in Albany, Oregon, a man named J. A. W. Heidecke approached McKinley and stated that he had lived for a long time at a little place called Detroit within thirty miles of Township 11-7, and had heard of 12 people making proofs to homestead claims in that township, and also that he was informed that McKinley and I were at the bottom of the deal. He knew very well that none of the entrymen had been on their claims, nor had they complied with the homestead law in any manner. Heidecke hinted that unless he could get something out of it, he would report the matter to the commissioner of the General Land Office.

The upshot of this conversation was that McKinley settled with Heidecke by paying him $50, for which amount he agreed to keep his mouth shut. A few months after the proofs had been made, “lookout Tarpley” learned through Special Agent C.E. Loomis, that he had received instructions from the Commissioner of the General Land Office to make a thorough examination of our 12 entries in Township 11-7, charges of fraud having been filed against them by somebody. Immediately upon learning these facts, I consulted with F. Pierce Mays, my attorney in Portland, who advised that I consult with C. E. Loomis, Special Agent for the Oregon City Land District, suggesting it would be an easy matter to “fix” things with him. Thereupon I wrote Loomis at Oregon City, stating that I would like to see him, as I was the owner of all 12 claims. Loomis professed to be well acquainted with Mr. Mays and questioned me rather closely regarding the entries.

I told him I had purchased the claims in good faith and was naturally anxious to secure the patents. I suggested that he make it convenient to visit the claims personally at the earliest date possible and report his findings to headquarters at Washington without delay. Mr. Loomis lost no time assuring me that he would do everything in his power to have matters adjusted. Thus encouraged, I went on to explain to Loomis that the trip to “11-7” would prove an arduous one, and quite expensive and I would gladly contribute to the expense if he would proceed to the township named.

Thereupon, I handed Mr. Loomis a draft in the sum of $500 and informed him that, upon receipt of patents, I would give him a similar sum after the patents were issued. I then wrote to J.E.W. Heidecke, requesting him to meet me in Albany, Oregon, where I wished to see him on important business. Some days later, I met him in Albany, and we proceeded to business immediately. I asked him if he was much acquainted in Township “11-7”, to which he replied, that he had lived in Detroit for the past 15 years and was not only familiar with the township itself, but was personally acquainted with every homesteader residing within, and, in fact, with all the settlers in that part of the country.

I informed him that I had purchased the 12 claims, and learned that Special Agent Loomis would soon reach Detroit, on a tour of inspection of the improvements. I told Heidecke that I wanted him to accompany Loomis and show him the improvements on each quarter section. I then told him he would be well paid for his trouble and handed him $10 to cover his expenses to date in coming to Albany, and an additional $100 to cover the expense of his trip to the mountains, when Loomis arrived. Heidecke then consented to make the trip and would conduct Loomis all over township “11-7” and would show him the cabins and other improvements on the 12 claims, and in addition, agreed to introduce the Special Agent to several residents of Detroit who were “personally acquainted” with each homesteader.

I instructed Heidecke to have a saddle horse for the special agent to ride, in addition to a pack animal, as Indian trails were the only available routes into the region. I also cautioned him to take along plenty of good things to eat and drink, particularly emphasizing the latter, and to take the best care of the old man, with a view to have him make a favorable report. I impressed on Heidecke that much depended on him and if he succeeded in showing all the cabins, improvements, etc. to Loomis, I would give him $250 more for his extra trouble. When I told him about the prospects of getting this additional amount, he responded joyously, “Good; just leave it to me.”

Heidecke then inquired if I was personally acquainted with Binger Herman, then Commissioner of the GLO in Washington, D. C. “I certainly am,” I replied. “Well, do you think you have enough pull with him to secure my appointment as a forest ranger, Heidecke asked.” I assured him that I had and would see that he was appointed as soon as I returned to Washington, and expected to go there as soon as Loomis had filed his report. Some 3 weeks later, I met Loomis in Portland, when he informed me of having just returned from his trip to Township “11-7”, advising me that he had made a careful examination of the alleged improvements with Heidecke, whom he pronounced very much of a gentleman, rendering him every possible assistance in his work.

Loomis then declared that they had found all of the improvements on the 12 claims in question, and had found sufficient evidence of habitation to justify the issuance of patents, and would recommend the entries to patent. Heidecke had merely taken Loomis along some well-defined trails that led past cabins belonging to other settlers and had not been on any portions of T11S, R7E, since they would have had to possess the agility of a goat to reach those “paper claims” which were practically inaccessible. (see Figure 3)

Heidecke later confided that after showing Loomis a certain cabin, belonging to a legitimate settler in another township, he circled around for about a half hour and rode back up to the same cabin, but viewing it from the rear. Since he was running short of cabins, he halted Loomis for the third time, viewing it from the side. Little did Heidecke know that his guest was only too glad to be fooled.

C. E. “Chuck” Whitten graduated from Santiam High School in Mill City, Oregon in 1963. He then attended Oregon State University and graduated in Forest Engineering in 1967. He and his wife Sharon moved to Vancouver, Washington where he then went to work for the Washington Department of Natural Resources, working on road location and surveying for timber sales. In 1972, he joined Hagedorn, Inc, a private surveying and engineering firm in Vancouver. In 1973, Sharon and I bought a 5 acre parcel in the woods several miles east of Battle Ground, WA. In 1975, we began building our own home there on weekends and holidays, finally moving in 1978. We had a lot of help from 2 other OSU Forest Engineers who had previously built their own houses. I had helped them which taught me a lot about what to do and not to do. In 2009, I retired as Vice-president of Hagedorn, Inc. which now gave us time to work around our house in the woods. We did a lot of backpacking with our two boys in the Cascades, mainly around Mt. Jefferson, the Three Sisters, and even Mt. St. Helens before she blew her top. Sadly, my wife Sharon passed away in 2017 and I spend most of my time now working on our “claim”.