Ideological boundaries are nebulous compared with those land divisions precisely marked out by surveyors. Both types of divides were on display in a 2008 U.S. Supreme Court case, New Jersey v. Delaware, 552 U.S. 597, concerning the Delaware River border between the two states and a proposed riverfront industrial plant and shipping terminal.

Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the National Press Club, April 17, 2014.

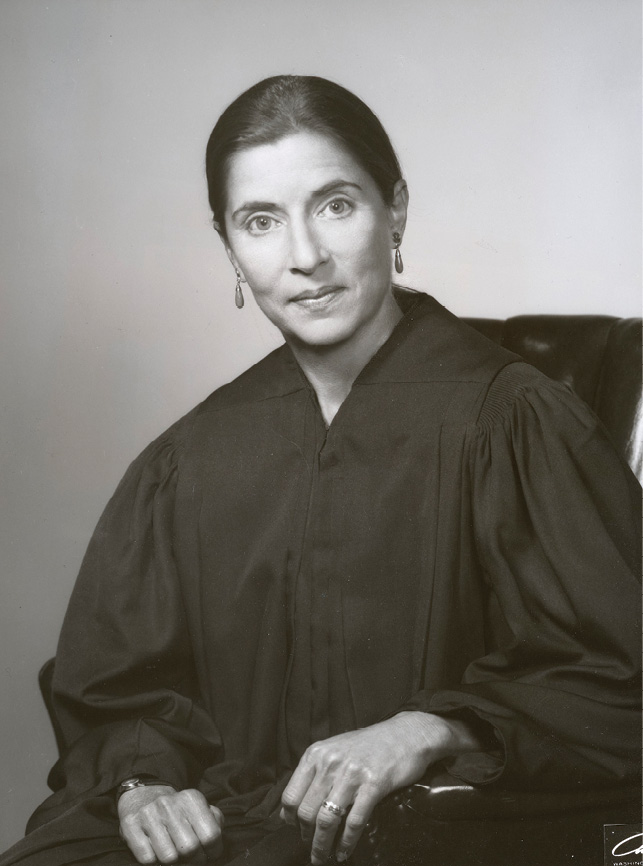

The Delaware case matched two titans of recent Supreme Court history: Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for the majority, and Antonin Scalia, in dissent, who were known for ruling from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum. Central to the case is the method of statutory interpretation known as textualism, which, together with its cousin, constitutional originalism, Scalia famously elevated above other forms of judicial reasoning.

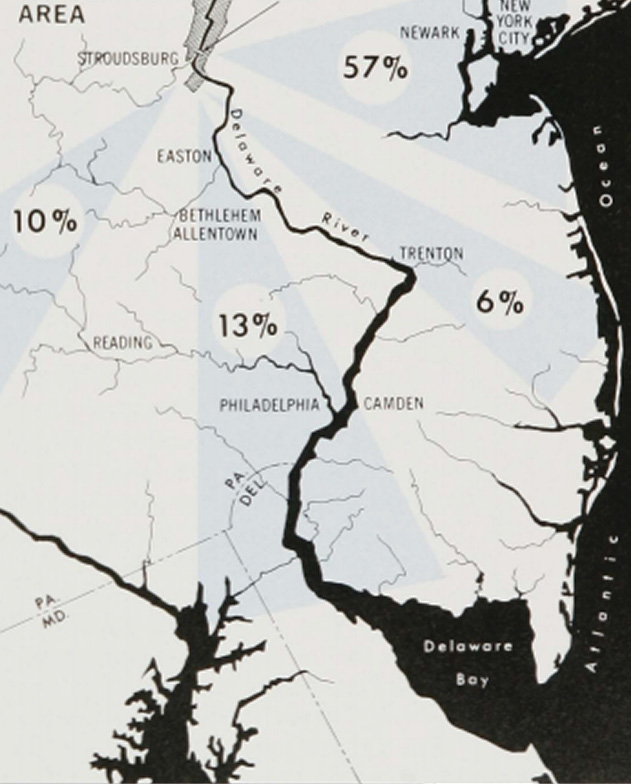

Vicinity map of Delaware River, ca. 1968, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Detail from “Approximate apportionment of visitor sources for Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.” WIKIMEDIA

Today’s conservative Court’s faith in these methods has enshrined Scalia’s legacy. But his approach continues to be controversial for its fixation on the meaning of words while discounting other factors, such as the purpose of the law and the consequences of the ruling. Among the approach’s detractors, retired Justice Stephen Breyer, whose tenure on the Court shared 21 years with both Ginsburg and Scalia, proclaims his resistance in his new book, Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, Not Textualism.

New Castle Courthouse, built in 1732, Georgian style. The cupola is the center of the 12-mile circle that forms Delaware’s northerly boundary. PHOTO BY CHARLES J. ADAMS III

Despite Scalia’s record on the bench, it is misleading to label textualism as a tool of conservatives because judges of all stripes employ multiple modes of statutory interpretation as a matter of course. For Ginsburg, remembered as a liberal champion for gender and racial equality, we will see in Delaware how she beat the textualist Scalia at his own game.

The LNG Project

In 2004, British Petroleum sought to build a facility along the Delaware River in Logan Township, New Jersey, to process, store, and transport liquefied natural gas (LNG). The project envisioned “a gasification plant, storage tanks, and other structures onshore in New Jersey, and a pier and related structures extending some 2,000 feet from [the] shore,” where supertankers would berth and off-load. “In transit, the ships would pass densely populated areas; a moving safety zone would restrict other vessels 3,000 feet ahead and behind, and 1,500 feet on all sides of a supertanker” (552 U.S. at 606).

Delaware from the Best Authorities, ca. 1814, hand-colored map published by Mathew Carey. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

But the project faced a roadblock, namely, the state boundary. A 1934 Supreme Court case had “conclusively settled the boundary between the States,” which, at the project’s location, runs along the low water mark on New Jersey’s shore. Thus, “Delaware owned the river and the subaqueous soil within a twelve-mile circle centered on New Castle, Delaware”—the arc that forms Delaware’s unique northern border.

Supreme Court building, Washington, DC. PHOTO BY JOE SOHM (JOESOHM.COM)

Due to the boundary, Delaware’s approval was needed to build and operate on the river. British Petroleum applied to Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, which refused to allow the project based on the state’s Coastal Zone Act. Designed to protect the natural environment, the law called for “control of industrial development” and expressly “prohibit[ed] the construction of new heavy industry in its coastal areas.” (Del. Code Ann. tit. 7, § 7001.)

Curtis Island Liquefied Natural Gas facility in Queensland, Australia. PHOTO COURTESY BECHTEL

In response, the state of New Jersey brought suit under the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in cases between states. New Jersey challenged Delaware’s power to deny the project, citing the states’ 1905 Compact that governed certain uses of the river, approved by Congress pursuant to the Compact Clause. (U.S. Const. art. I, § 10.) Further, apparently taking Delaware’s snub as an aggressive shot across the bow, one state legislator reportedly proposed “recommissioning the museum-piece battleship U.S.S. New Jersey [moored upriver at Camden] to repel an armed invasion by Delaware.”

Interstate Compact

In Delaware, New Jersey sought a ruling that “the 1905 Compact gave it exclusive regulatory authority over all projects appurtenant to its shores.” That Compact had resolved the states’ decades-long litigation, largely over fishing rights, yet notably it “left location of the interstate boundary an unsettled question,” to be fought another day (ultimately decided in 1934).

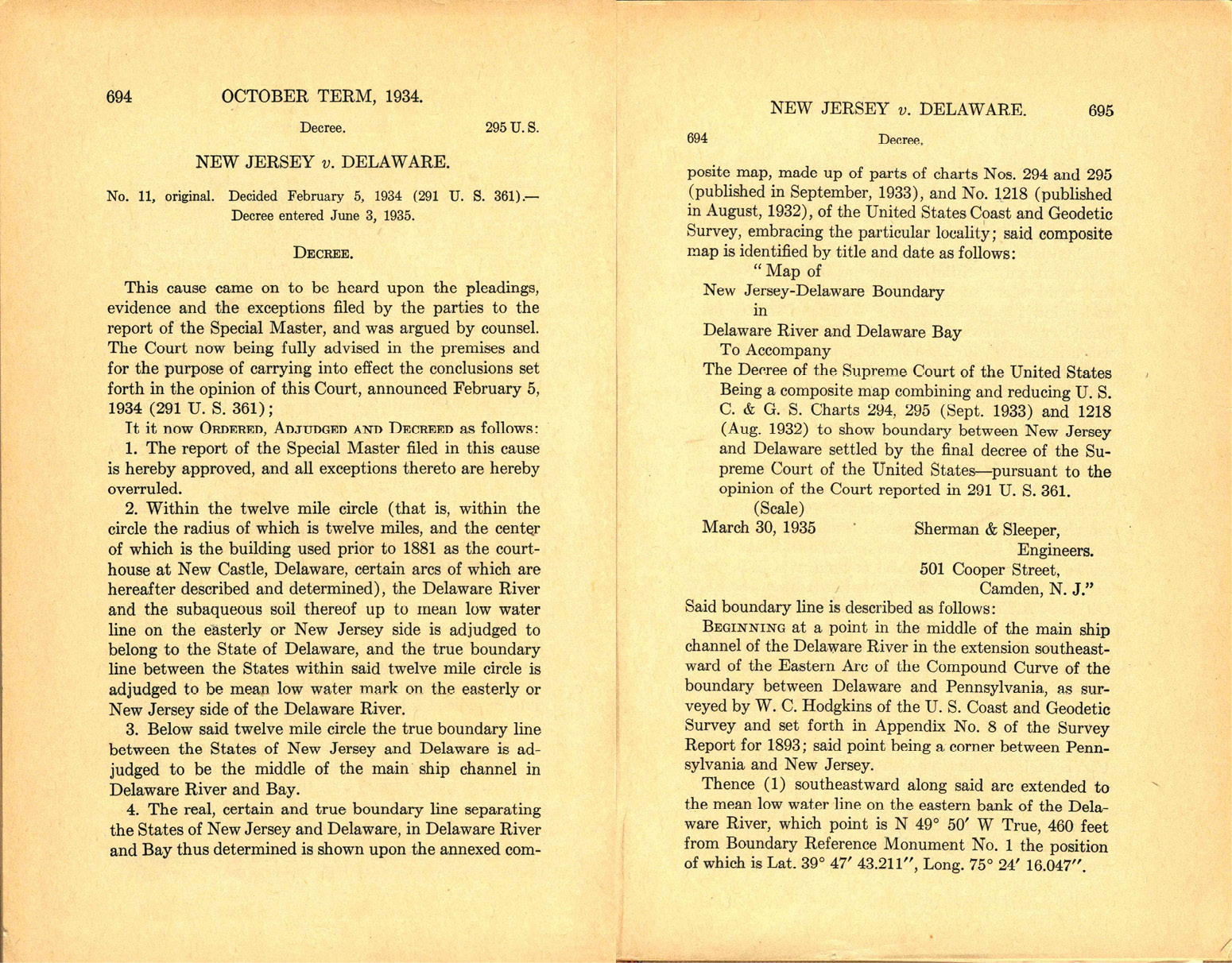

Excerpt from 1934 Decree in New Jersey v. Delaware, 295 U.S. 694, describing the “real, certain, and true boundary line separating the states.” UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE LIBRARY

Relevant to interpreting the Compact was this “recognition of the still-unresolved boundary,” evident in the care taken to avoid the surrendering by either party of any land or power. Article VIII of the Compact states:

Nothing herein contained shall affect the territorial limits, rights, or jurisdiction of either State of, in, or over the Delaware River, or the ownership of the subaqueous soil thereof, except as herein expressly set forth.

New Jersey relied on a different provision of the Compact addressing time-honored riparian rights. (Surveyors know riparian boundaries. The word is derived from the Latin, ripa, meaning “bank” or “shore,” which also gives us “river.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary.) Article VII of the Compact provides: “Each State may, on its own side of the river, continue to exercise riparian jurisdiction of every kind and nature ….”

As the Court (i.e. Ginsburg’s majority opinion) explained, interstate compacts are interpreted “just as if we were addressing a federal statute.” Although the meaning of the adjective, riparian, is well established, the Court in Delaware was tasked with interpreting “riparian jurisdiction,” which it called a “novel term” and “a verbal formulation devised by the drafters specifically for [the Compact].” In the law, jurisdiction means power or authority.

“No Thumb on the Scales”

Scalia’s co-authored book, Reading Law, describes textualism as “The exclusive reliance on text when interpreting text.” To put this into practice, the book cites the fixed-meaning canon or principle: “Words must be given the meaning they had when the text was adopted.” Relevant to the LNG project, this method also “embrace[s] later technological innovations. Hence, a statute referring to aircraft” would still apply to unimagined flying machines in the future.

Scalia maintained that textualism was an objective method of statutory interpretation that favored neither conservative nor liberal outcomes. In Delaware, interpreting the term “riparian jurisdiction” required understanding the trade-offs the two states had negotiated in the 1905 Compact. Joined by Justice Samuel Alito, Scalia’s dissent frames his textualist approach, denying any bias: “The only issue is what sovereign powers were yielded, and that is best determined from the language of the Compact, with no thumb on the scales.”

Wharfing Out

In “endeavoring to fathom the import of the novel term ‘riparian jurisdiction,’” Ginsburg and Scalia seemed to agree on the outside contours of what the term means and does not mean, while reaching different conclusions as to the intermediate gray area.

The wharf at Fort Mott State Park, NJ. The Supreme Court cited the fact that Delaware issued a permit in 1996 to refurbish the stone pier projecting into the river. On the horizon is Reedy Point Bridge. PHOTO BY ARK. NEYMAN

At one end (i.e. what it means), they agreed that under common law, riparian landowners enjoyed “the right of access, [which] includes the right to erect wharves to reach the navigable portion of the stream” (quoting a 1904 treatise by H. Farnham). Accordingly, “Delaware’s counsel conceded at argument that Delaware could not impose a total ban on the construction of wharves extending out from New Jersey’s shores” (Stevens, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment). To Scalia, the LNG project “would have been viewed as an ordinary and usual riparian use at the time the two States entered into the 1905 Compact.”

At the other end (i.e. what it doesn’t mean), the justices ostensibly agreed the power was not exclusive. Or did they? Scalia writes, “I willingly concede that exclusive riparian jurisdiction is not the same as ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ simpliciter [simply].” But notice what he added there. The term in the Compact is “riparian jurisdiction,” yet Scalia renders it “exclusive riparian jurisdiction.” This sleight of hand explicitly strays from what Scalia refers to as the omitted-case canon, a pillar of textualism: “Nothing is to be added to what the text states or reasonably implies.” (Scalia & Garner, 2012.)

Scalia explains away his insertion by arguing it is implied by the Compact’s promise of riparian jurisdiction to each state “on its own side of the river.” This “implicitly excludes” jurisdiction on the other side of the river, meaning that Delaware necessarily lacked authority over New Jersey’s shoreline improvements. In Scalia’s view, “There was no need, therefore, to specify exclusive riparian jurisdiction.”

To the contrary, the Court found the concept of concurrent jurisdiction logical and consistent with the Compact and thus held the states had “overlapping authority to regulate riparian structures.” In other words, New Jersey was free to construct “ordinary and usual” wharves, for example, and Delaware could prohibit heavy industry.

Public Rights

Ginsburg steered clear of detailing the environmental consequences of a ruling that would let New Jersey thwart Delaware’s coastal protection law. Rather, the Court’s opinion is pure textualist, a classic exercise in Scalia’s supremacy-of-text principle: “The words of a governing text are of paramount concern, and what they convey, in their context, is what the text means.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1981 as a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals, D.C. Circuit. WIKIMEDIA

In using the term, “riparian jurisdiction,” the parties to the Compact knew that riparian rights were not absolute; those rights were understood to be subject to government regulation. The Court quoted Farnham (rights of riparian owners “are always subordinate to the public rights, and the state may regulate their exercise in the interest of the public”) and an 1894 Supreme Court case, Shively v. Bowlby (“a riparian proprietor … has the right of access … and to construct a wharf or pier, subject to such general rules and regulations as the legislature may prescribe for the protection of the public”). The authority to prohibit certain uses in the interests of the public health, safety, and welfare is known as the “police power.”

Scalia found it difficult to reconcile the state’s police power with the admitted right to build a wharf. His dissent argues, “If Delaware could forbid the wharfing out that Article VII allowed, [then] Article VII was a ridiculous nullity.” Contrary to this overstatement, think about everyday zoning regulations. Although property owners may unquestionably have a “right to build” on their own land, that right is restricted, for example, in terms of building size. And in residential neighborhoods, zoning typically prohibits commercial uses such as restaurants and nightclubs. Such commonplace regulations protect communities without rendering property rights a “nullity.”

Words in Their Context

The Court held that the Compact “did not secure to New Jersey exclusive jurisdiction over all riparian improvements commencing on its shores.” Quoting the Special Master’s report, the Court reasoned that in the context of the then-unresolved boundary, “Delaware would not have willingly ceded all jurisdiction over matters taking place on [submerged] land that Delaware adamantly contended it owned exclusively and outright.”

To drive the point home, Ginsburg referenced other state river boundaries that shed light on options the parties in 1905 were certainly aware of. An 1834 compact between New Jersey and New York involved the states’ common boundary along the Hudson River. As with the border in Delaware, it was located at New Jersey’s shore. Yet there, the compact gave New Jersey “the exclusive jurisdiction of and over the wharves, docks, and improvements, made and to be made on [its] shore.”

And in an 1877 arbitration over riparian rights on the Potomac River, Virginia and Maryland had considered a boundary that outlined all existing and future wharves and improvements, thereby containing them within the sovereignty of the onshore state. (Virginia v. Maryland, 540 U.S. 56, fn. 7 (2003).) The Court in Delaware concluded, “New Jersey could hardly claim ignorance that Article VII could have been drafted to grant New Jersey exclusive jurisdiction.”

The Court held that Delaware’s authority to deny permission for the LNG project was “consistent with the scope of its retained police power” to protect against—in the words of the state’s Coastal Zone Act—“a significant danger of pollution to the coastal zone.”

Consequences

Delaware serves as a reminder that textualism and the importance of words are not strictly the domain of conservatives, just as consideration of outcomes is not solely reserved for liberals. In fact, in his dissent in Delaware, Scalia saw fit to point out the missed economic benefits of a natural gas project, such as jobs and tax revenue, for “an energy-starved Nation.” Some see this as inconsistent, coming from a justice who criticized “consequentialism” as evincing an “uncanny correspondence between the consequentialist’s own policy views and [that jurist’s] judicial decisions.” (Scalia & Garner.)

The case also reminds us of the celebrated friendship and mutual respect that Justices Ginsburg and Scalia shared, despite their political differences. In her eulogy for Scalia, Ginsburg described how, in a landmark equal protection case (United States v. Virginia), her preview of Scalia’s “searing” dissent had the effect of strengthening her majority opinion. Perhaps that same relationship dynamic was at work in the Delaware case.

Bibliography

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, et al., My Own Words (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

Richard L. Hasen, The Justice of Contradictions: Antonin Scalia and the Politics of Disruption (Yale Univ. Press, 2018).

Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (Thomson/West, 2012).