Scripture envisages a time when “Every valley shall be lifted up/ every mountain and hill made low / and the uneven ground shall become level .…” (Isa. 40:4 (RSV).) While the meaning of this prophecy is quite another story, the imagery fits one surveyor’s mission to transform Seattle at the turn of the twentieth century.

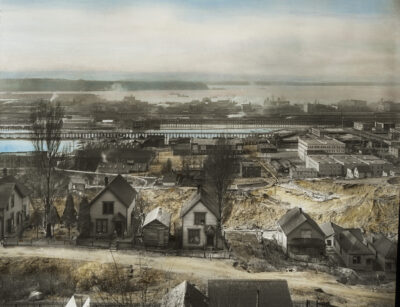

Seattle was established on the hills and tidal mud flats along the eastern shore of Elliott Bay, a natural deep-water port in Puget Sound. Fed by a Mount Rainier glacier, the Duwamish River carried timber and coal to Elliott Bay for trade. The region was blessed with natural resources, but regular flooding on the low-lying wetland stymied construction, and the steep rise landward was seen as a hindrance to a viable commercial center.

Beacon Hill regrade overlooking Elliott Bay (Lantern Slide Collection 2002.3.485). Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI)

We will use the backdrop of Seattle’s twenty-year campaign to cut down hills and fill tidelands to illustrate legal concepts affecting real property, among them constitutional takings, special benefit assessments, and the duty to shore up your neighbor’s land known as lateral support.

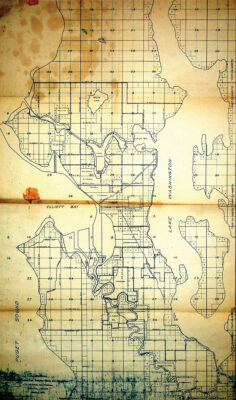

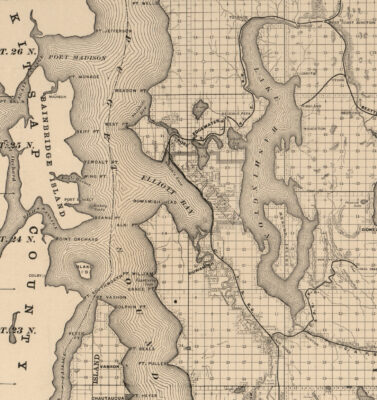

Map of Seattle, 1914, showing sections, government lots and annexations. Blueline on linen. Court engineering records (Series 2608-05). Seattle Municipal Archives

R. H. Thomson

The surveyor who brought his dream to fruition was Reginald Heber Thomson (1856-1949), born to a devout, well-to-do family in Indiana. Perched above the Ohio River, their home’s commanding views of woodland and the riverfront city of Madison may have informed Thomson’s perceptions of the interplay of nature and civilization, and, as he himself observed, “the causes of city growth.”

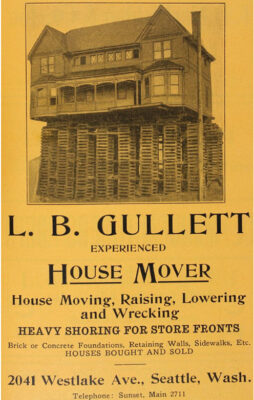

Advertisement, 1911, in Polk’s city directory. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections

Exerting a strong influence on Thomson was his father Samuel, a math professor at the Presbyterian Hanover College and a preacher and biblical literalist. (He strove to reconcile the emerging science of geology with Genesis holy writ in an 1857 lecture.)

Thomson was also shaped by the Progressive Era and would become one of its leading apostles. In addition to social and political change, this period is known for the pursuit of science and engineering to overcome hurdles, which the journal Science embraced in 1901 as the dream of “directing the great sources of power in Nature for the use and convenience of Man” (Croes, 14(342), 83).

Graph of relation between horsepower and grade, 1913. Seattle Engineering Dept. (Series 2613-07). Seattle Municipal Archives

In 1884, Thomson became Seattle’s city surveyor and seven years later King County surveyor. The next year, Seattle appointed him city engineer. In addition to removing hills, Thomson is largely credited with other Herculean achievements for the city, including its water supply pipeline, sewer system, the straightening of the Duwamish River for industrial use (today a Superfund site), and the ship canal connecting Lake Washington with Puget Sound.

The Regrade Plan

Recounting his work with a railroad survey party in Washington state, Thomson wrote of “the confidence this crew had in Seattle’s future” among their banter. Adding his own far-seeing two cents, Thomson recollected challenging them with: “How will people in one end of the city be able to do business with those in the other end, with such hills and deep valleys between them?”

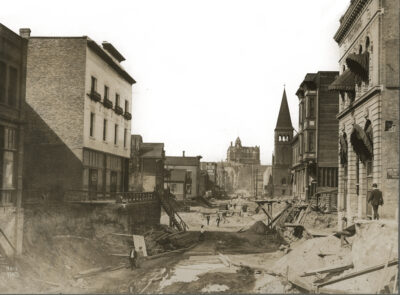

Regrading on Third Avenue near Spring Street, Seattle, 1906. Photo by Webster & Stevens. In the distance is the grand Denny Hotel, completed in 1903 and razed three years later when the hill was lowered about 100 feet. Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI)

In the days of horse-drawn transport, steep grades disrupted travel, physically dividing the city and making it costly to pump water to homes. As city engineer, Thomson was a tireless advocate to Seattle’s politicians and residents for regrading the hills. For each individual project, the process required a petition signed by a majority of affected property owners and a city council ordinance, like the one “providing for the improvement of Jackson Street and other streets in the city by grading and regrading the same.” (Gerard, 73 Wash. 519 (1913).)

In accordance with Thomson’s plan, the city excavated only the grid of roads, while landowners bore the cost of bringing down their own intervening lots—ideally at the same time and using the same contractor (Wilson, 2009). Harnessing the power of the Cedar River, water cannons disintegrated the hills, and their constituent alluvium was channeled downhill to reclaim the tidelands, creating 27 new city blocks.

Authority to Regrade

Although the regrades garnered widespread support, some no doubt questioned the very power asserted by the city to lower the streets and oblige the population to adjust correspondingly. (Reportedly “the city used eminent domain to bully recalcitrant residents” (Klingle, 2007).) But just as the law typically enables local governments “to open [originally] and keep in repair streets, lanes, alleys, etc.,” that same municipal function includes “the power to alter the grade or change the level of the land on which the streets … are laid out,” the U.S. Supreme Court previously held. (Smith v. Corp. of Washington, 61 U.S. 135 (1857).)

Water cannons regrading Denny Hill, ca. 1906. Photo by Webster & Stevens (1983.10.8164). Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI)

The question leads to property law’s abiding discourse: the tension between individual rights and the greater good. In Smith, the Court denied a claim stemming from the regrade of K Street in Washington, D.C. There the Court ruled that the “plaintiff may have suffered inconvenience and been put to expense in consequence of such action; yet … private interests must yield to public accommodation.”

While legal challenges did not put a stop to Seattle’s regrading, the law did entitle landowners to compensation for certain losses, such as buildings impaired or destroyed in the course of the work. Because each property was unique, the extent of restitution depended on the feasibility of whether “buildings might be lowered [in situ,] or moved off the premises and moved back after the lots were cut down to the regrade, [or] whether they were a total loss.” (In re Jackson Street, 47 Wash. 243 (1907).)

What kept such compensatory damages to a minimum (and became a factual issue for the courts) was the inevitability that a new commercial district would increase land values. The law permitted the city to offset the monetary damages by the demonstrable benefits of leveling the grade, “for if the market value of the property … will be enhanced by the improvement, there would, manifestly, be no pecuniary loss, and therefore no legal damage.” (City of Seattle v. Bd. of Home Missions of Methodist Protestant Church, 138 F. 307 (9th Cir. 1905).)

A Search for Purpose

Thomson’s path to the Pacific Northwest was not a straight line. After completing his studies at Hanover, including “special courses in surveying, chemistry, and geology,” Thomson moved to California where his father had accepted a position as headmaster of a Christian college in Sonoma County. During his four years in California, he taught at his father’s school and worked as a surveyor with his brother, including mapping a subdivision of the Rancho Tzabaco (Wilson).

Detail from Anderson’s New Map of King County, Washington Territory, 1888, published by Anderson, Bertrand & Co. Library of Congress

Biographer William Wilson reckons that Thomson’s upbringing instilled in him a certain virtue tinged with church doctrine. In a simile Thomson wrote in his autobiography, biblical resurrection gives rise to self-improvement: “[I]t is necessary for us to be crushed for service so that we may rise again into a new life and to a new beauty, as it was for the rock to be crushed that it might display itself in the flower.” While the tenor is personal, the action evokes a landscape transformed. In Seattle, Thomson found a city not yet fully formed; a land where he might show his promise.

Special Benefit

The idea of rising property values did more than reduce the city’s liability for damages. It justified requiring landowners to contribute to the cost of regrading with a “special assessment” levied against the affected parcels. A special assessment is a method of financing public improvements that differs from a general tax in that it applies only to specific land. Examples of its application include streets and sewers and other

local improvements that are appurtenant to specific land and bring a benefit substantially more intense than is yielded to the rest of the municipality.… A valid special assessment … is merely compensation paid by the property owner for the improved value of his land.

(Heavens v. King County Rural Library Dist., 66 Wash.2d 558 (1965).) The existence of a benefit is evidenced by “the difference between the fair market value of the property [before and] after the special benefits have attached.” (Id.) Whereas the amount to be levied is each property’s “proportionate share of the cost of the improvement.” (In re City of Seattle, 66 Wash. 327 (1911).) A city may not levy an assessment greater than the special benefit accruing to that property.

In the case of the Seattle regrades, a panel of eminent domain commissioners heard expert testimony and established the parcel assessments, which were then confirmed or modified by the city council. The assessments were subject to judicial review. (Id.)

Challenging Assessments

In addition to divining dollar worth, the bewildering difficulties involved mapping the precise “zone of benefit”: why one lot should be assessed and the next one not; and distinguishing between what to consider a special benefit, versus what aspect of the regrade benefited the public generally and hence should fairly be borne by general fund revenue. (Id.; see In re Taylor Ave., 149 Wash. 214 (1928) (the court held certain assessments for the regrade of Seattle’s Denny Hill had been “fixed on a fundamentally wrong basis [because any] benefits as do accrue are clearly general benefits and the property is not chargeable therefor”).)

These judgment calls and valuations were inexact, to say the least. “No questions come to this or any other court,” said the state Supreme Court, “that involve such entanglements and complications as do these assessment cases. They cannot be resolved by reference to equation or theorem.” (66 Wash. 327.)

The court quoted one of the assessment commissioners who admitted, “The damages or benefits cannot be figured out.” And this from the trial judge: “Justice in its abstract sense is impossible.” Strikingly resigned, the high court said, “All we can hope for, then, is that no greater injustice is done to one than to another.”

Taking or Tort

The law draws distinctions when identifying the legal rights at stake, and the results can be consequential. We rely on courts to “determine into which class a given case may fall.” (Wong Kee Jun v. City of Seattle, 143 Wash. 479 (1927).)

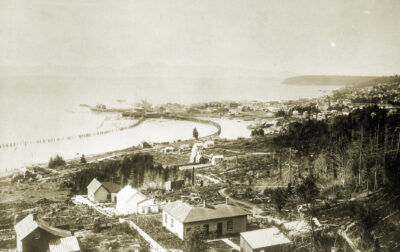

Then: Stereopticon photo by Carleton Watkins, view from Beacon Hill. Caption in Thomas Prosch photo album reads: “Seattle in 1882 from Dearborn Street and Twelfth Avenue South looking NW.” Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI)

Wong Kee involved damage to property from the city’s regrading. The lawsuit alleged that cutting into the hill, without providing sufficient slope or shoring, caused plaintiff’s neighboring land and improvements to slide into the void. The shoddy excavation violated the rule “that the owner of land has the right to the lateral support from the adjoining soil.” Thus, if one “removes the soil from his own land as to deprive the adjoining owner of [that land’s] natural support,” he is liable for the resulting damage. (Id.) A jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiff, and the city appealed.

The question for the state’s high court was whether this harm was an unconstitutional “taking” of plaintiff’s property or should more appropriately be considered a tort: a wrongful act on the part of the city, in this case performing the work negligently or carelessly. The plaintiff argued it was a taking. Property damage from public works, even unintentional, can certainly be ruled a taking, as when flooding from a storm sewer gives rise to a claim that the government has in effect used private property for a public purpose (i.e., a retention pond) without compensation. (See Bunch v. Coachella Valley Water Dist., 15 Cal.4th 432 (1997).)

For reasons that will become apparent, the city argued the claim was a tort. Torts are mainly creatures of state law, which means legislatures can procedurally limit their availability. One common way lawmakers do this is with claim-filing requirements, which tend to reduce the tort risk exposure for local governments.

Before suing a city, these laws mandate that a potential plaintiff first attempt an administrative claim for damages, usually within a relatively short time after the harm occurs (30 days in Wong Kee). If not rejected, the claim gives the city a chance to right the wrong or make a calculated payout, if only to avoid litigation. A failure to timely file a claim will prevent courts from reaching the merits of the lawsuit, and, in the case of Wong Kee, would have barred relief. But this procedural hoop may not interfere with the highest earthly rule in American law, which requires compensation for property taken.

A Just Result

The court’s task in Wong Kee was to apply takings or negligence law. Focusing on carelessness as the cause of the slide favored the negligence conclusion: “[W]hen the city blindly and willfully proceeds by reason of such inadequacy of plan to damage private property, it is acting tortiously.”

Now: Seattle today. In foreground is Pioneer Square, a national historic district. Courtesy Shedbuilt.com

But in “look[ing] further for the dividing line,” the court was reluctant to allow the city its self-serving preference: “[T]o do so would be to take advantage of its own wrong, which is abhorrent to well-established legal principles.” This value-laden language is an example of moral reasoning, a judicial approach to decision-making that places at the fore the Constitution’s core convictions, such as the right to property. In Wong Kee, the court clearly sought to protect the individual and ensure a just outcome. The court said the city “cannot plead a willful wrong [a tort] to defeat a just claim [a taking].” Accordingly, the court affirmed the award of compensation under the Constitution. (U.S. Const. amend. V.)

Gridlocked

It is evident from his long career as a public servant that Thomson valued the use of engineering know-how to improve his city and the lives of its people. Over the past century, our society has become less single-minded when it comes to altering the environment. But even when the regrading of Seattle’s hills was underway, an editorial posed a sincere vision: that the city, with its “magnificent natural site, [was missing] a great opportunity to lay out its streets to conform with the natural features” (Klingle).

The writer was plainly referring to choices in road alignments. Seattle’s roads unremarkably followed a strict grid pattern, unwaveringly reflecting the platted sectionalized land without heed to the severity of the grade. Whereas roads attentive to contours might be longer, they are designed for gentle incline and can inspire a sense of harmony with nature. It’s hard to imagine the havoc to private property being any worse had the city elected to redesign its streets rather than eliminate its hills.

As our respect for the natural environment and awareness of our place within it evolve, the story of Seattle’s regrades gives reason for pause before pushing on to remake the world in our image (alluding to Gen. 1:26).

Bibliography

Matthew Klingle, Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle (Yale Univ. Press, 2007).

R.H. Thomson, That Man Thomson (Univ. of Washington Press, 1950).

William H. Wilson, Shaper of Seattle: Reginald Heber Thomson’s Pacific Northwest (Washington State Univ. Press, 2009).