I have been working on an immense land acquisition for open space for nearly a year now. It has been drama from Day One for everyone I am working with (I’ll call us “Team A”) and continues to be a source of insomnia as deadlines repeatedly are pushed back to address newly revealed problems. I will refer to the seller of this property as Big Corporation, but some may figure out its business. The point of today’s story is that surveys matter, title searches matter, diligence and doing the right thing matter.

I have been working on an immense land acquisition for open space for nearly a year now. It has been drama from Day One for everyone I am working with (I’ll call us “Team A”) and continues to be a source of insomnia as deadlines repeatedly are pushed back to address newly revealed problems. I will refer to the seller of this property as Big Corporation, but some may figure out its business. The point of today’s story is that surveys matter, title searches matter, diligence and doing the right thing matter.

Team A had a title search conducted by a long-standing title company. The resulting 500-plus pages of deeds fell into my lap as the summer of 2021 wound down, and I spent many hours employing a magnifying glass and my best code-breaking skills. Not every 19th century deed scrivener had the clearest handwriting. Between “thick and thin” pen strokes that cause parts of letters to fade out over time and ornately scrawly script that is tough to decipher even when clear, I did a lot of translating for the rest of my team members.

Not everything I told them was welcome news. In several instances, conveyances for fair market value restricted the land’s use for a stated purpose, and upon cessation of that purpose title would revert to the grantors, their heirs, successors, or assigns. A century and a half after those transactions, and years after the stipulated use ended, tracking possible claimants presents a daunting task. Statutes of limitation for claims to real estate interests are the saving grace here.

Then there was the matter of matching what is on the ground in terms of land use with what is in the public record that the title company searched. The perimeter of this mega-acquisition is encroached upon by fences, sheds, swimming pools, garages, and even dwellings. There is even a line of utility poles through the tract, but no deed addressing it. It turns out that Big Corporation didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to some of the encroachments, and for others, it issued either licenses or leases. None of those documents were recorded.

Why is there no utility easement? The answer is monetary. With an easement, the landowner (as the servient estate) receives a one-time payment. With a lease or a license, the rights of the lessee or licensee must be renewed every so many years, so the conditions can be revised and the price to renew can be increased.

Why are there no easements or land conveyances for major and permanent encroachments like houses? While Big Corporation should never have allowed those trespasses in the first place, by issuing land leases instead of easements, once again Big Corporation remains in control of terms and conditions.

Why not record any of these documents? At least in the states where I practice, there is no statutory requirement to do so. But even unrecorded, they are still enforceable contracts, signed by both parties. Once again, money plays a role. It is not free to record documents in the public registries.

Herein lies one reason a complete survey is so important in land acquisition, and why it should be done prior to closing rather than afterwards only as a prelude to development. When field work reported on the survey points out land uses that are inconsistent with public records, red flags should fly, delaying closing until after resolution of those discrepancies. Title insurance doesn’t cover anything that is revealed after closing, so finding these things out ahead of writing the final check is important.

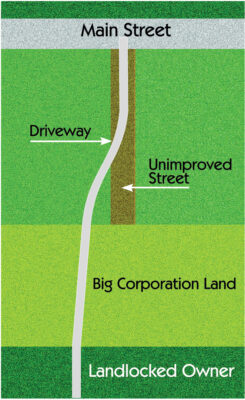

The site condition sparking this column was a driveway from a landlocked parcel crossing over Big Corporation’s land to access public roads. There was no recorded easement and no unrecorded license or lease, despite Big Corporation’s awareness of the situation for a long time. Way back in the chain of title, the grantor to Big Corporation’s predecessor reserved rights to some form of access to the rest of the municipal road network, whether by private or public road. Nothing further was ever put into writing. The result was a winding driveway that instead of going straight into the platted public road’s right-of-way stub also encroaches (without an easement) on someone else’s land on its way to that connection. (See the illustration accompanying this article.)

Team A told Big Corporation to formalize an appurtenant easement with the landlocked parcel owners in the location of the present driveway. Big Corporation’s response was to prepare a lease agreement – adding in boilerplate language to require the landlocked owner to provide proof of a $2 million commercial insurance policy to continue to use their driveway.

Team A found recorded evidence of use of that driveway for at least 90 years; the original deed with the reservation for access was recorded 150 years ago. Current owners of the landlocked tract would have a good chance of winning a quiet title action for access without having to buy a mega-policy for something they and their predecessors had used freely for so long. Big Corporation finally relented and prepared an easement document.

The moral of this diatribe is that surveyors have much to contribute during land transactions. Our knowledge of field and title aspects should be employed to alert clients to problems they may not be aware of and point them to possible resolutions