The one person on the survey crew that is completely indispensable is the helicopter pilot. The job could not be accomplished without them. Their expertise or lack of can make or break the job. It is also a thankless position. They see no official recognition of what they do. They are not noted or recorded in the survey records as pilots, field assistants, or any other title. Only as a small statement in the official field note record that the survey was accessible by helicopter. So here is this article I write to recognize these heroes of our industry. The names mentioned here have not been changed to protect anybody’s identity so I’m probably going to catch flak sooner or later.

Adam Goad is the epitome of a rotorhead. No fixed wing aircraft for him. Just rotors. When he’s not flying helicopters he’s flying his gyrocopter.

When I first started surveying for the BLM back in 1980 all the pilots on our cadastral jobs were out of the military. Vietnam Vets. Many with Combat experience and it showed. Not only in their piloting expertise but also their character. One of our pilots, Gene Schnell was a Chinook pilot during the war. Totally laid back, quiet ladies man type guy. He flew that Bell 206 like it was a Chinook…very very slow with meticulous wide turns…If you wanted to get on point fast, forget it…it wasn’t going to happen, but you weren’t going to die either…an extremely safe flyer. Then there was Steve Culver, he piloted a Hughes 500. A caricature of himself. Overweight version of a GI Joe and just as plastic. All nomexed out with his survival knife strapped to his calf and his Colt M1911 strapped to his hip. He would come in for dinner in the evening and order a large steak, Raw, not cooked in anyway, just right out of the packet, raw. He had humor and he was humor. Damn good pilot though. He flew the Hughes 500, that model was built for him. An extension of himself. There were some memorable jobs on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula.

One time I was setting a survey monument on the side of a slope, practically a cliff and up alongside he appears in his helicopter. Just hovering there in front of us to the point of annoyance. I figured he prob had the Boss in there doing inspections of the field crews. Couldn’t tell for sure because of the glare on the bubble. I finally got irritated enough, set my equipment down, turned around, dropped my pants and mooned the helicopter. It worked; it flew away. After my corner was set, I called him in to pick us up. He arrived laughing his head off. I said, “What’s up?”, he replies, “Do you know who you mooned?, that was Annie McKenzie” The young lady Proprietor of the hotel I was staying in. She was getting a free helicopter ride. I turned and looked out the bubble. I thought about committing Hari Kari on the spot, but then I said to myself no, I’ll just quit my job and move to another country. Less pain.

That was a pretty good summer when it was all done. Steve ended up going to Maui to fly tourists around in Alaska’s off season. There was an incident with his 500 when the engine suddenly lost power while climbing near a crater rim. It crashed and rolled. He survived but his passengers were newlyweds, and the groom was killed. I heard he gave up flying after that. That’s the one thing about that occupation. It’s incredibly unforgiving. The helicopter is not meant to fly, it’s unstable. The pilot is just there to convince it to fly, to correct the forces of chaos, to steady the unsteady.

Checking out the Jesus Nut. They call it that because if that nut comes off in flight your last words are “Jeezus!!”

In 1985 we were doing a survey of the Alaska Railroad for BLM. The Railroad was being transferred to the State of Alaska after being in Federal jurisdiction since its inception. 500 miles of railroad needed the survey with monumentation set 100 ft. each side of the centerline at the crossing of the section lines. The main field survey took 5 years, starting in Seward and finishing in Fairbanks. I’m sure I could probably write a book on the events that took place during that operation. But here I will focus on one, The survey of the railroad tunnel to Whittier. The tunnel starts in Bear Valley about 45 miles South of Anchorage and runs to the coastal town of Whittier. It initially started as only a train tunnel but now is comprised of both Train and Vehicle travel. A normal daily operation today is that a train will past through then venting of the tunnel takes place, after a few moments it is open to vehicle traffic in one direction only and then a half hour later it is open to the cars and trucks passing through in the other direction and repeat.

Today it is known as The Anton Anderson Memorial tunnel. The tunnel itself was built in 1942 by the US Army during WW II to facilitate moving cargo and supplies between Cook Inlet and the deep-water port of Whittier Sound. It’s 2.52 miles long and is the longest highway tunnel and longest combined rail and highway tunnel in North America. It is not uncommon to enter the tunnel in Bear Valley under sunny skies and exit the tunnel in Whittier in pouring horizontal rain and wind. It passes through Maynard Mountain, a 4137 ft. summit named after helicopter pilot, Robert L. Maynard, who had crashed his CH-21 on the mountain in 1964 in dismal weather conditions while ferrying emergency supplies during the Good Friday Earthquake. When you look at a CH-21 today you do kind of wonder how that thing can get off the ground. It’s a helluva configuration. Helicopters have sure come along ways since those days.

The 200 feet of the railroad right of way not only extended through the mountain it also extended straight up to the top surface of Maynard Mountain where a total of 6 monuments needed to be set. Although most of the Alaska Railroad ROW survey could be done on foot and by rail this area had to be done by helicopter using the Inertial system, also known as the Auto Surveyor. The Auto Surveyor was a large box of electronics that took up the back seat of a Hughes 500. It would initialize on a control point at the Survey Base then fly to the target area with its position in the X, Y, and Z updating continuously and independent from any external signals or data sources. Once at the position where the monument needed to be set the operator running the inertial system would drop a bean bag out of the door. The pilot using a right-angle periscope device would hover over the bean bag and using a trigger on the stick would mark its position.

A move would be calculated from the bean bag to the true position of the ROW point. That move would be given to a 2-man monumentation crew who would fly in a separate helicopter, a Bell 206, and using staff compasses or theodolites make a positional move from the bean bag to the ROW point and set the monument which would be an iron post, aluminum rod or tablet if it happened to fall on a rock. You couldn’t wait too long between dropping the bean bag and returning to the bean bag because bears would end up finding it and disturbing it by moving or even eating it. This happened more than a few times. The bags were actually made out of fluorescent pink material that was derived from fish scales. Not too smart. We ended up dipping the bags in a solution of cinnamon and formaldehyde to deter their curiosity with some success.

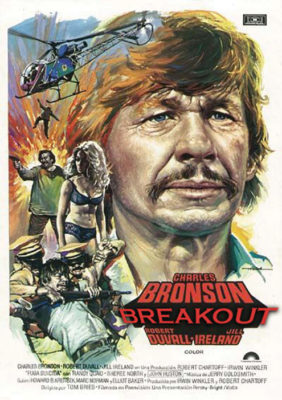

I was assigned along with surveyor Mike O’Connor to set those monuments on top of Maynard Mountain. Our helicopter pilot was Roger Hershner. Now Roger was some kind of character. He was a great pilot, a good man, with a great sense of humor. He did a lot of BLM and Forest Service work, particularly firefighting. But it was his personal events of prior that he never brought up unless you asked him about it, then he would go right into the details. You see, Roger was the helicopter pilot who landed in a prison yard in Mexico in 1972 and extracted an inmate, a convicted murderer, and made a getaway in what was the first helicopter prison escape in history. The deed was outlined in a book called “The 10 Second Jailbreak” by Eliot Asinof. It then went to Hollywood and was turned into a movie called Breakout, with action star Charles Bronson playing the role of Roger Hershner.

This is the only existing photo of monumenting the ROW atop Maynard Mountain with Roger in the Helicopter and Mike O’Connor on the theodolite. Yeah, I know it’s a crappy shot. From a small compact Olympus film camera I used to carry, but I guess it wasn’t crappy enough, so I accidently introduced a light leak while changing the film roll. It took us two days to set those six monuments. Accessories to the corner point were 7” deep drill holes that I sunk into the bedrock using a 3/4” star bit and 3 lb. hammer. Caveman by todays standard of using lithium powered electric tools to cut into the rock.

The bad end of the bird. Unlike the main rotor, this one hangs head high. Don’t want to end up like that guy at the end of the Charles Bronson movie.

That project was the last time I saw Roger. He continued on working with the Forest Service out of Washington State for years. In 2009 he was ferrying a Bell 206 Jet Ranger to Virginia when an unknown catastrophic mechanical event occurred. He tragically lost his life when his helicopter impacted in a wheat field in the flat lands of Kansas of all places.

Nunivak Island was an interesting project. A large island off the west coast of Alaska within the Bering Sea. We were tasked with surveying historical sites around the island and setting stainless steel posts. Our helo on that job was a MD500. The pilot was Dave Beard, A big guy that didn’t seem to fit inside the cockpit in a comfortable manner. One day we went out to set up a GPS base station on a control point and then to fly over a river to drop myself off for the survey. He went back to Base Camp to pick up another crew. Later on, a thundering sound caught my attention. I looked over across the river towards the base and in the distance was a herd of about 200 caribou. They were running… more than running…they were in stampede formation. From the distance a fluid brown carpet that flowed with the rolling tundra and they were heading directly for my base. I called Dave to see if he could herd them away, but he was already out of reception of my radio. That herd barreled right up to the base antenna and suddenly stopped. An unknown alien feature in their natural world. That was enough to spook them 180° in the opposite direction and off they go. That base station saved itself.

Dave finally caught up to me and off we go to the next target site. Gary Kowal our field supervisor called us over the radio and asked Dave if there was a height requirement for passengers to ride in the 500. We both look at each other, “height requirement?” When we get back to basecamp we meet our newest surveyor helper. Jakub Kowalski, an international exchange student from Poland. He was a member of a Polish university basketball team and he stood over 7 feet tall. I stared at the sky as I shook his hand. He took up the entire back seats of the helicopter and practically had to lie over sideways to do it with gear shoved in here and there where ever it would fit. I don’t think he lasted but a few days.

The density of mosquitos and other assorted bugs can be so great that a layer of insect remnants can form on the rotors affecting its aerodynamic design.

In the 1990s Bell helicopters started getting phased out for survey work along with the Vietnam Veteran pilots who flew them as they pursued retirement. The new helicopter on the block was the gasoline powered Robinson 44, The new pilots were a lot younger, damn near teenagers in some cases. The R44 is a great little utility helicopter. Far cheaper to charter than those fuel guzzling turbine engines. A lot quieter as well. Gawd…that turbine scream in a MD500 just pierces your skull. Totally destroyed my hearing over the years, and most pilots as well. In the R44 the sound is more like running a lawn mower instead of a jack hammer. you can actually talk/yell to each other instead of having to use sign language. The chopper sits lower to the ground making it easier to get in and the main rotor sits on a mast so you’re less likely to get your head chopped off.

Mark Shelton was a good pilot to work with in Gates of the Arctic National Park. A New Zealand guy. I actually wrote another article about that particular project for American Surveyor. I heard he cut his own tail off unfortunately. Which can be done if the dynamics of the helicopter is just right, and the Rotor disc is pulled back sharply. Luckily, it was during a landing and there were no injuries.

Mark Shelton was a good pilot to work with in Gates of the Arctic National Park. A New Zealand guy. I actually wrote another article about that particular project for American Surveyor. I heard he cut his own tail off unfortunately. Which can be done if the dynamics of the helicopter is just right, and the Rotor disc is pulled back sharply. Luckily, it was during a landing and there were no injuries.

The glide ratio for a R44 is about 4:1, which means that if that engine quits on you then it has the ability to auto rotate 4 feet forward with every 1 foot drop in altitude. Hopefully giving the pilot enough time and space to find a suitable spot for a safe landing. For comparison, a small, fixed wing airplane like a Cessna 206 has a glide ratio of 9:1. Pilot Swiss Chris, from Switzerland, always flew with this ratio in mind. If we had to cross any body of water he would gain altitude to make sure we got nose bleeds and also to have enough space to make it to the other side. Well Alaska is a state full of wetlands so working with Swiss Chris was an up and down venture all day long. Some bodies of water are just too wide but also impractical to fly around so we would cross regardless. Those portions of the flight were usually done in silence with your ear on the purring of the engine.

Here’s a photography tip when shooting helicopters. The Rotor of an R44 under full power spins the entire 360° in 1/14th of a second. So, if you set your cameras shutter speed to about 1/13th to 1/15th of a second and pan the helicopter you will get a photo of the entire rotor disc instead of a frozen blade. It’s a slow shutter speed so it is a bit tricky. It’s best done with a DSLR with a rapid-fire drive. Out of a dozen blurry shots you’ll usually get a decent one.

Mike Grady is a pilot we use now and then. His main gig is as a crop duster pilot so when you’re flying with him you better have a strong stomach or a sick bag in your shirt pocket. He’ll make you use it.

Quintin Slade, who has the coolest name in the universe according to my wife, is a multitalented rotorhead, he can fly anything that spins. Even a brick if it rotates fast enough. He can set a helicopter in the tightest of spots even when you are looking at it and going there is no way it’ll fit. Toe ins: when only the toes of the front skid touches ground, no problem. Single skid toe-ins, no problem. Hover ins where you jump out of the air to the ground, he does it. Tree ins, where you climb out of the chopper into the top of a tree and climb down to the ground, easy for him but I usually end up scratched to pieces. Spider ins and sling outs, well I won’t talk about those, don’t want the FAA knocking on my door. Some pilots are by the book, and some are more resourceful pushing the envelope. If you have a gnarly survey on steep forested terrain he’s the man. He always wanted to help out on the survey as well. We had to take the machetes and sharp objects away from him and explain why. “Well Q, it’s because neither of us can fly the helicopter.” He would whine “ Oh yeah, I’m just a dumb stick wiggler, can’t possibly survey.” We would laugh.

One day he flew away to refuel and came back with a large pepperoni pizza. My first pizza delivery by air.

That’s just a few of the great pilots in the surveying industry that I have had the pleasure of working with. I hope to be able to continue surveying in areas where access is by helicopter.

Daryl Moistner is licensed in Nevada and Alaska and a globe-trotting photographer. He currently lives in Oregon and works throughout the American West and Alaska.