Upland Conveyances, Generally

Where’s the Southerly Boundary? 1. All lands north of the stream. 2. All lands north of the stream’s north bank. 3. All lands north of the stream’s south bank. 4. South “to the stream’s north bank, thence westerly along said bank ….”

For nearly all states, on a river navigable for title, the upland’s riparian boundary with the State (owning the riverbed) will be either the ordinary high water line (OHWL) or the ordinary low water line (OLWL). (This article concerns inland nontidal rivers.) On a nonnavigable stream, the upland’s riparian boundary with the opposite adjoiner will be the thread of the stream. (BTW, exactly where is the “thread of the stream?”) When conveying an upland tract, unless some very explicit, clear indication is expressed otherwise, the instrument will convey all the land the grantor owns…to the OHWL/OLWL or the thread.

For boundary descriptions with phrases like “to the river then along the river,” “all lands north of the river,” “all lands south of the south bank of the river,” “to the bank then along the bank,” “to and with the river,” “to the river’s center,” “to the river thence along its bank” and like phrases, if the grantor owned to the OHWL/OLWL or thread, and barring an unusual exception, the conveyance will be to that line. The presumption is that the grantor conveyed all he or she owned. This includes all of grantor’s lands gained by accretion whether mentioned in the conveyance or not and whether formed by natural or artificial means. All of grantor’s lands will be conveyed, even if the acreage stated is for the uplands and does not include accreted acreage.

The presumption of conveying to the OHWL/OLWL or thread when the deed says “to the bank and along the bank” has been explained by the courts, saying that it is against public policy to create (or leave) small strips (between the bank and the line) in remote grantors. This is particularly true when the strip has no use to the grantor and would benefit the grantee. Leaving a strip between the bank and the OHWL/OLWL or thread of the stream seems illogical. Such a strip, if left in a grantor, would make the grantee’s lands nonriparian with no access to the water. Phrases such as “to the river,” calling for a natural monument (the river), in the order of importance of conflicting title elements, trumps all other elements of the description. It extends the call to the center of the monument and as far as the grantor owns. This is also true for artificial monuments such as pins, survey markers, walls, trees and stones. And, applying that the grant is interpreted most strongly against the grantor legal principle, the questionable strip will be conveyed to the grantee.

For a nonnavigable stream, consider the hypothetical: Owner A owns a tract through which the stream flows generally north-south. Owner A conveys to B “all lands west of the river;” then A conveys to C “all lands east of the river.” The boundary between B and C will be the thread of the stream, A does not retain ownership of the streambed.

For a nonnavigable stream, there could be an exception to the presumption that the thread of the stream is the boundary. Consider this hypothetical: Owner A owns a tract through which a nonnavigable stream flows generally north-south. Owner A conveys to B “all lands west of the east bank of the river,” then later A conveys to C “all lands east of the east bank of the river.” (This exact circumstance has been before the Arkansas Supreme Court.) In this example, the thread presumption has been overcome, Junior/Senior rights will prevail: The east “bank” will be the boundary. The bank will be the boundary, but exactly where on the bank is the boundary line?

Another variation on this hypothetical: Owner A conveys to B “all lands west of the east bank of the river,” then later conveys to C “all lands east of the river.” This is a Junior/Senior rights situation. You can’t convey what you don’t own. The boundary will be the bank (with its associated location question). Note that to properly survey C’s land, the surveyor will need the adjoiner B’s deed to check if the deeds “mirror,” there being no gap or overlap. Here there is an overlap, easily discovered and cured.

There may be some reason to exclude a riparian strip from a conveyance of the upland (although it is hard to imagine why). If a grantor wishes to exclude a near-river riparian strip, it would be best practice to write the boundary description such that it includes the strip then excepts it. However, in doing so be aware that the grantee won’t be riparian but that by future erosion the excepted strip may be washed away, making the grantee riparian. Of course, the excepted strip, retained by the grantor will gain land if the stream moves by erosion and accretion “away” from the grantee’s parcel.

Some Examples, Where’s the Southerly Boundary?

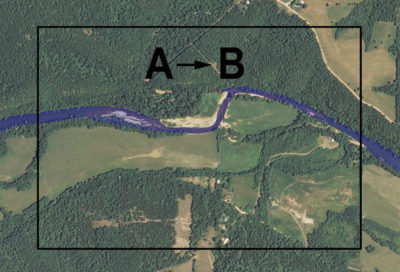

Supposing for example, there’s a generally east-west stream that crosses a tract. Here are four examples of different ways lands to the north of the stream could have been described and conveyed. The question is, where is the southerly limit of the lands conveyed using these descriptions. (Let’s assume the stream is nonnavigable for title.)

- All lands north of the stream.

- All lands north of the stream’s north bank.

- All lands north of the stream’s south bank.

- South along some line “to the stream’s north bank, thence westerly along said bank” to some line, thence northerly….

Let’s look at each of these descriptions

- All lands north of the stream. For this description, it is highly likely the southerly title line is the thread of the stream, but not a certainty. This “likelihood” needs further title research. If Owner A originally owned the lands on both sides of the stream and then, as the common grantor conveyed “all lands south” then “all lands north” and, through mesne conveyances those descriptions have been used, then, no doubt, the boundary will be the thread of the stream. (But, where exactly, and with specificity is the “thread?” I’ll leave that topic for another article.)

- All lands north of the stream’s north bank. One may believe the boundary is the north bank, but this may not be correct. This boundary determination will require title research. Suppose Owner A owned both sides of the stream and sold to C “all lands south of the stream” and sold to B “all lands north of the stream.” Then B conveyed to D using the description at issue here, “all lands north of the stream’s north bank.” A strict interpretation of these conveyances would result in B retaining ownership of the lands between the stream’s thread and its north bank. Owner D, being conveyed only to the bank, is not riparian. Did he or she really intend to purchase a tract adjacent to a stream that is not riparian? Did B really intend to retain half the streambed?

Applying the court’s reasoning and legal principles previously discussed, Grantor B conveyed all that he or she owned, D would own to the stream’s thread. Owner D’s southerly boundary will be the thread.

- All land north of the stream’s south bank. This description will require title research. If Owner A originally owned on both sides of the stream and that common grantor first conveyed to B all lands north of the south bank and later conveyed to C all lands south of the south bank, then the south bank will likely be the boundary. Here the question is a Junior/Senior rights question, not a riparian boundary question. From the conveyances, it looks like the grantor knew what he or she was doing. The question will become exactly where, with specificity and repeatability, is the boundary on the “bank” located? And note, C will not be riparian. Through the gradual processes of erosion and accretion, as the stream’s bank moves, so moves the boundary.

- “To the stream’s north bank, thence westerly along said bank….” Again, this boundary description will require further title research. Suppose Owner A originally owned the lands on both sides of the stream and conveyed to C “all lands south” and conveyed to B “all lands north.” Then Owner B conveyed to D using the atissue boundary description given above. Under this scenario and for the same reasoning as given in Example 3 above, D’s south boundary would be the thread of the stream (not the bank). The courts have said the presumption is that the grantor conveys all he or she owns. If Owner B owned to the thread, then that person’s grantee was conveyed to that line and not the bank.

Title History Important

In construing boundary descriptions for riparian tracts, in nearly all instances research into the title history will be required. That research will be required back to when an original grantor split the lands, divided by the stream. If, in the original “split,” the description made the boundary the thread of the stream, then by just about any subsequent mesne conveyance descriptions, no matter how described, the riparian boundary will remain the thread of the stream, that being the presumption. Only through some very explicit conveyance or exception will this presumption be overcome.

Caveats and a Suggestion or Two

- Riparian and littoral boundary location can be complex and can be very statespecific. Most states have no statute law pertaining to the boundary description construction issues discussed above. The applicable legal principles will be found in case law. And, as the caveat to every boundary control legal principle warns, the contrary or an exception may be shown. Complicating the location of a riparian boundary is the fact, as illustrated here, the title history (as well as the fluvial geomorphology) will be critical in determining the boundary location.

- Never use the term “bank” when describing a riparian or littoral boundary. The question will be, exactly where, with specificity and repeatability is the boundary located? Will it be the “high bank” or the “low bank” or somewhere in between? Exactly that question spent the 1920s in the Supreme Court of the United States, the “Red River Litigation” case between Oklahoma and Texas. The central issue in that litigation, the location of the south bank of the Red River is a kerfuffle that continues to this day. (In that litigation the SCOTUS invented the gradient boundary, a term/boundary location used only on the south bank of the Red River and in Texas.)

- Meander lines are just about without exception never the boundary line for a tract adjoining a waterbody. There are only a very few extreme exceptions to this rule, but that is the subject of a future article. Be very careful when using a meander line in a boundary description of a riparian tract. Actually, using a meander line when describing a riparian tract is probably not best practice. There are better ways to describe riparian tracts without using or describing a meander line. (I’ll leave that topic for another article.)