Over the past several years I’ve been on the sidelines of a sad affair about a landlocked property that has an access easement but is still inaccessible. It isn’t that the servient estate burdened by the easement won’t allow the landlocked owner to use the easement. It isn’t that there is an adverse claim to part of the landlocked property and the owners—or maybe I should say the assessed owners—are being denied use of their land. It is a matter of old deeds with multiple tracts that leave a gap where the access easement should connect. All of this translates to both unmarketable and uninsurable property.

Over the past several years I’ve been on the sidelines of a sad affair about a landlocked property that has an access easement but is still inaccessible. It isn’t that the servient estate burdened by the easement won’t allow the landlocked owner to use the easement. It isn’t that there is an adverse claim to part of the landlocked property and the owners—or maybe I should say the assessed owners—are being denied use of their land. It is a matter of old deeds with multiple tracts that leave a gap where the access easement should connect. All of this translates to both unmarketable and uninsurable property.

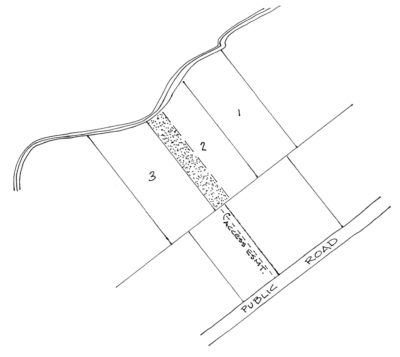

There are multiple surveying and title aspects to this story, which I have simplified a bit in the sketch. It is a particularly troubling tale right now because the owner who had wanted to sell the land finally passed away at age 101 before the title could be straightened out. It is her children (none of them exactly youthful, either) who are now trying to bring the sale to completion at this point.

The property in question is comprised of three tracts, each described by metes and bounds in chains and links. As is probably evident by the sketch, this is wetlands, so it isn’t buildable, but it is perfect for a wildlife conservation area, a purpose the land on the other side of the creek already serves. The difficulty is that the middle of the three tracts making up the property bounded by the creek is the one that connects to the access easement over the property fronting on the public road. The access easement benefits all three tracts, so that isn’t the problem. That front property is owned by other family members, and there is no antipathy here, only a legal problem.

Instead, the holdup is that the shaded area of the middle tract is not included in the deeds within the family as it moved from one generation to another. Somewhere along the line, deeds have somehow not included that strip, likely from a scrivener’s error. The title to that strip seems to have been omitted way back in the chain, its source not yet found. And if the easement leads to that strip for which ownership isn’t known, then any entry through that shaded area to reach the rest of Tracts 1, 2, and 3 constitutes trespass.

Without legal access, the property is uninsurable. Title insurance companies will raise exceptions for properties lacking access to a public road—if they will even write a policy. Without access, the property is also unmarketable, meaning a reasonably prudent purchaser isn’t likely to buy “as is.”

How can this be resolved? The top answer is a quiet title action. We mostly think of quieting title as quelling any adverse claims to a property. But no one else claims this land. The descendants of the deceased centenarian believe they own it, just as their mother had believed she owned it. Over many years, various members of the family certainly have been paying taxes on it. There isn’t clearly what we call color of title, meaning documentation that gives rise to the belief that a tract is part of a conveyance, because the tract is definitely not included in the bounds of what is described. What we are left with is not adverse possession but peaceable possession.

Depending upon the state, commonwealth, tribe, or territory in which the land resides, peaceable possession cases are argued under different rules from what applies to adverse possession. Peaceable possession is continuous and undisturbed by any attempts to dispossess the claimants.

Adverse possession requires open, notorious, exclusive, non-permissive, and actual possession for whatever period of time that state’s laws stipulate. Payment of taxes isn’t often a requirement because most assessors just want to be paid, and it doesn’t matter by whom. But payment of taxes can indicate a belief that one owns the land—or that one wants to. I know of two examples where payment of taxes in bad faith was meant to help swing the balance of evidence towards devious non-owners.

Hostility isn’t always required either, as mistaken claims meeting all the other requirements satisfy the statutes and courts in some jurisdictions, but the non-permissive part is always a factor. That simply means there has been no request to use the land (users either believing they have the right or having a “Just do it” mindset) and that no one has allowed entry by saying, “Yeah, you can use my land.” Acquiescence, by lack of words or action to eject someone from the land or by preventing someone from entering in the first place, builds a case for peaceable possession. That of course means that there had to be some notice of the use or entry, being the notoriety aspect accompanying the open possession of the land.

This is a good place to point out that claims for possession, whether peaceable or adverse, don’t have to show that every square foot of the property is being used or is enclosed, or that it is used all year round. Claims can succeed where it is shown that the property was best suited for something less than full-time 100% occupation. That might be helpful in this situation. The biggest hurdle is, of course, having to file the suit for a court hearing. That’s not free. And hopefully the judge will understand real property law, too.