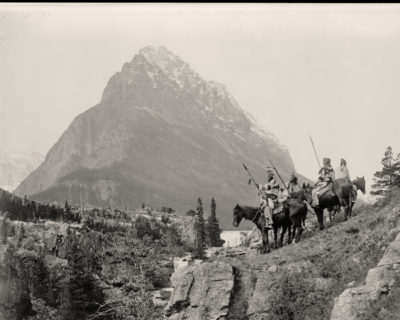

Reed, Roland, photographer. The Land Mark. , ca. 1912. Nov. 4. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2006684432/

I’m a real history buff and I will use almost any excuse to dig into the past and learn something new. Last year, when we celebrated Columbus Day, which is increasingly being celebrated as Native American Day, led me to a related surveying question—How are Indian Trust Lands surveyed?

Quite a few of my past blogs talk about early surveying, but I haven’t really gone into how the land came to be owned by the government in the first place. It’s a brutal history that still affects all of us today. I’ve included a couple of links at the bottom of this article that summarize that history and provide additional insight.

Moving on to the Indian Trust Lands subject—I happen to have completed specialized coursework in this area since I first earned my CFedS back in 2012. It’s helped me perform a wide range of cadastral services within Wisconsin, including surveys on Native American lands. So why is it recommended that special certification should be acquired to survey on Indian Trust Lands? The short answer is because there are additional considerations (vs surveying privately owned parcels). A prescribed national approach was developed to handle these considerations.

The longer answer

Rothstein, Arthur, photographer. Cheyenne Indian houses. Tongue River Reservation, Montana. United States Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation Montana Rosebud County, 1939. June. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017777748/

Here’s the longer (and more interesting) answer that describes how Indian Trust Lands can be challenging.

The U.S. Government began allotting land to Native Americans in 1798 through treaties (which are defined as legally binding agreements between nations). After 1871, Congress declared that no further treaties would be made and all future deals with Native Americans would be through legislation only.

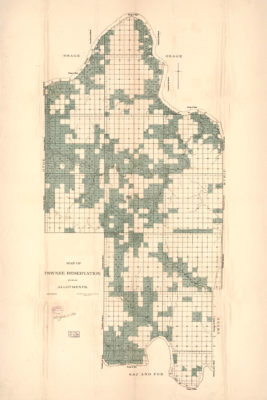

Even with legislative decrees, these laws continued to be based on allotments, and in 1887, the use of allotments became national policy. The General Allotment Act authorized the president (at the time it was Grover Cleveland) to survey tribal land and divide the area into allotments for individuals and families, with the idea that they would be farmers like many homesteaders were. Of course, this didn’t take into account whether Native American families wanted to farm or whether the land was even tillable.

The president had the discretion to decide where and when to apply this law to native lands. Members of the tribe (or those indigenous people living on the reservation) were given permission to select tracts of land for themselves and their children (usually 40 to 160 acres). If the tribal members didn’t do that, the tracts were assigned by a BIA agency superintendent. “Surplus lands” could be sold to the federal government. Over the years, 60 million acres of land were either ceded outright or sold to the government as surplus lands.

Allotment, not ownership

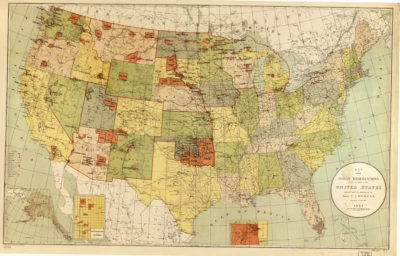

United States Office Of Indian Affairs, and T. J Morgan. Map showing Indian reservations within the limits of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Office of Indian Affairs, 1892. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009579467/.

Even though Native Americans had allotments, they didn’t technically own the land. Only those homesteaders who actually purchased the land could sell or do what they wanted on their land because they had legal title to it. Conversely, the federal government retained ownership of Native American’s allotments, which were held in trust.

That meant that they couldn’t sell or lease their land for 25 years after the allotment was granted; before that time, the federal government had to approve any transactions. The result of this is that many Native Americans sold their land after 25 years, since, in many cases, the land had never met their needs.

The General Allotment Act continued to be amended over the years, and these amendments resulted in the loss of another 27 million acres of Native lands. The shoddy administration of Native lands became so alarming that a law was passed in 1934 (the Wheeler-Howard Act) that ended the process of allotment on Native lands in the contiguous United States. That meant that all remaining trust allotments would remain in trust.

The problems caused by years of allotments, poor management and corruption remain. Fractionated ownership of Native land titles, checkerboard ownership patterns on many reservations, loss of access to sacred sites are just a few of the issues.

BLM Cadastral Surveys

Allotments in Kansas, back in the day. Hudson-Kimberly Pub. Co., Cartographer. Map of Pawnee Reservation showing allotments. [Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Pub Co, ?, 1893] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016586525/.

My view

I came across some of these unique circumstances in Northern Wisconsin when I was hired to survey a handful of roads that crossed some nearby Indian Trust lands.

When we think of a general public road here in Wisconsin, we think of a strip of land that the public has the right to use for transportation, and as long as it’s opened, maintained and/or used for that, it remains a public right of way. I learned that such roads that were built on Indian Trust land were treated a little different. They were a permitted use with an expiration date. And, as things tend to go, that expiration date had come and gone a couple years before I was hired.

After I started working on the project, I got to put my CFedS knowledge to the test. I gained the necessary permits needed for me to work on the Trust lands through the local tribal office. I was exempted to need a tribal member to escort me during my time working on the project, however sometimes it is required, depending on the nature of the work. Then I hit the ground compiling and completing all the necessary field work needed to create a map of definite location of the existing road and any existing facilities within the area. Additionally, I provided the client a description of the boundary of the area for the permitting process.

It was a fun project to be on, but definitely a learning experience as well. I got to use my CFedS training. I also got the chance to coordinate with agencies that I’d never worked with in the past. I designed maps according to federal regulations, which was also new to me. I also had the opportunity to learn more about a native culture that is nearly right outside my back door.

So, for anyone who may be on the fence about the CFedS program, I highly recommend it. Even if you don’t have any Federal Trust Lands near you, the background and education that I received just on the US Public Land Survey System alone is priceless. I challenge you to learn something new about Native Americans and Indigenous People. They have an incredible history! ◾

References:

https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/indian-reservations

http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.na.096

https://iltf.org/land-issues/history/