After my long hiatus from writing for The American Surveyor, its publisher, Marc Cheves, has persuaded me to again start contributing articles to this fine magazine. I put a lot of thought into what subject I should start out with, and I thought that the topic of quieting title to real estate—otherwise known as “an action to quiet title,” should capture the interest of many of its readers, and especially the land surveyors.

After my long hiatus from writing for The American Surveyor, its publisher, Marc Cheves, has persuaded me to again start contributing articles to this fine magazine. I put a lot of thought into what subject I should start out with, and I thought that the topic of quieting title to real estate—otherwise known as “an action to quiet title,” should capture the interest of many of its readers, and especially the land surveyors.

The process known as “quieting title” is necessary when the ownership of a parcel of land is in doubt. Sometimes attorneys, title examiners and surveyors often find that the title to a parcel of land is not clear and confusing from an examination of the public records, and therefore the ownership may be in dispute; and when such a doubt exist the law provides a judicial remedy for property owners to have determined the true ownership of the real property at issue.

Suits to quiet title are the traditional remedy to clear titles of certain defects; however such suits are likely to be complicated, time-consuming and expensive, especially when notices by publication and posting are necessary, and they can seldom be conducted to a conclusion in time to satisfy an impatient client.

In addition to curing title defects, by way of examples: unreleased mortgages, abandoned roadways and forged instruments in the chain of title, a quiet title action can be utilized to endorse a claim of adverse possession, providing that all of the elements can be met.

Without spilling a lot of ink on the pages of this article with legal quotes and citations from pertinent cases, I thought that the best and easiest way to describe the process by which disputed titles can be cleared of its “clouds” is to review the legal process of one actual case, without giving public exposure to all of the facts and the actual identity of the people involved.

That one such case arose when a certain Gordon Wrightfield approached his attorney seeking help to acquire a “deed” in his own name for an area of land which he and the community considered to be his family cemetery, and which Gordon alleged that he and his father before him had been maintaining it as their own for more than eighty (80) years, although the “record title” was in the names of others.

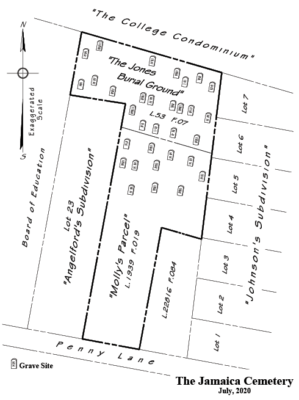

The cemetery, known as the “Jamaica Cemetery,” actually consisted of two (2) adjacent parcels of land, the total area of which being approximately one (1) acre. One of the parcels was owned of record by Gordon’s grandmother, Molly Wrightfield, who had acquired that parcel in 1939, and who died circa 1961; and the other parcel was owned of record by an Agnes Jones, who had acquired the property in 1887, and who died circa 1923.

Both Molly and Agnes died intestate—meaning that they had each died without leaving a last will and testament to be probated; and Molly’s parcel was simply referred to in the neighborhood as “Molly’s Parcel,” and Agnes’ parcel was simply referred to as “The Jones Burying Ground.”

All of the available public records were examined by the attorney, i.e., those records maintained by the land and wills offices, the law and equity filings, the taxing authorities, the plat records, and the state archives; and with many interviews being conducted with certain family members, all of whom had ancestors buried in the Jamaica Cemetery going back into the early part of the 19th Century

After listening to many antidotal stories about family relationships, lore and tales, including stories about unresolved personal disputes between family members, the names and purported addresses of at least 85 members of the Wrightfield and Jones families could be ascertained.

It was a given that not all of the members of the Wrightfield and Jones families were known, or whether they all were even living or dead, and then there is always the possibility of illegitimate children, whom no one wanted to acknowledge. Many known family members were scattered around the country, and were found to be located in various Maryland counties and cities, but also in the District of Columbia, Florida, Michigan, Nevada and Texas.

Except for a couple of small estates having been opened for a few deceased family members, solely for the purpose of transferring automobile titles as required by the state motor vehicle administration, no regular estates had been opened, thus making it next to impossible to completely and actually determine the genealogy of the respective families.

By modern day inheritance laws, each one of the 85 known members of the Wrightfield and Jones families, and all those unknown who could possibly trace their respective ancestry back to either Molly or Agnes, would legally own a small real property interest in the Wrightfield Cemetery were named in the complaint as defendants—that would, of course, include grandchildren, great-grandchildren, “long-lost” nephews, nieces, and cousins, etc. It was a certainty that there were many unknown descendants of Molly and Agnes who could not be identified, and therefore the number of persons who may have had some remote real property interest in the Jamaica Cemetery was certainly far greater than 85.

As a result of a boundary survey of the Jamaica Cemetery, 40 grave sites were identified, with not all of them being marked by monuments, and with many of the inscriptions being worn out by age and therefore were incapable of being read; and by observable ground depressions, it was obvious that there were other grave sites which were unmarked.

After the collection of the available evidence, a complaint to quiet the title to the Jamaica Cemetery was filed in the local circuit court, requesting that the fee simple title be ordered and decreed to be vested in Gordon Wrightfield, by the common law doctrine of adverse possession. Included as attachments to the complaint were verified releases which were obtained from a few of those members of the Wrightfield and Jones families who were willing to quitclaim to Gordon any and all of their respective interest in the Wrightfield Cemetery which they may have acquired by the laws of inheritance.

As required by various rules and statutes, service of process was achieved on all of the known defendants by personally serving upon them a copy of the complaint, along with a summons; or by certified mail, return receipt requested, when an address was known; and on the unknown defendants by posting a court ordered notice on the courthouse bulletin board, and by publishing the notice for three (3) consecutive weeks in a newspaper of general circulation, and by posting the same notice on trees in conspicuous places on both “Molly’s Parcel” and “The Jones Burying Ground.”

The named defendants in the complaint included all of the known persons who had been identified by research in the public records, and their addresses derived from the families’ oral histories; and included in the complaint were all of the unknown heirs, legatee, devisees, spouses, estates, personal representatives, testate and intestate successors of Molly and Agnes, and all other persons who may be claiming any interest in the subject properties.

During the litigation Gordon died and his widow was appointed as the personal representative of his estate, and thereafter she was substituted as the plaintiff in this case. Default judgments were entered by the court against all of those persons who had not responded to the complaint which had been served upon them in the manners as described above, and judgments were also entered against those defendants who had been personally served and had responded, but who did not appear in court on the day of the trial.

For all of the many persons who had been identified in the complaint as defendants, and who may have had some real interest in the subject properties, only two (2) appeared on the day of trial!

Much of the evidence concerned the manner in which Gordon and his father had taken care of the properties as if they were their own, by paying all the expenditures for the upkeep of the Wrightfield Cemetery, shoving snow, cutting the grass, racking leaves, removing fallen tree branches, cutting back the shrubby, getting rid of nesting bees, chasing off trespassers, picking up beer cans and condoms left after late night partying in the cemetery, paying the real estate taxes each year, cleaning up the grave sites and the funerary objects, setting a fire to burn down a dilapidated structure on the property, repairing the boundary fences, and giving permission to certain family members to have the remains of their deceased relatives buried in the Jamaica Cemetery, inter alia.

During the one (1) day trial, nine (9) witnesses testified as to their personal knowledge of the Jamaica Cemetery, including how and by whom it had been maintained; and as to their knowledge of the relationships between the members of both the Wrightfield and Jones families, The court’s opinion and order was entered four (4) months later, declaring that Gordon’s widow, as his personal representative, possessed the absolute title and ownership, in fee simple, to the Wrightfield Cemetery, which included both Molly’s Parcel and the Jones Burying Ground.

Thus, after many decades of uncertainty as to who actually owned this small piece of real estate, with its ownership being somewhat in limbo, the title had been cleared by an action to quiet title with a final court order declaring that Gordon’s widow was the legal owner—such an action being a very useful remedy to be used when one is in doubt as to the true owner of real property.

If any of the readers of The American Surveyor have any questions or comments about how the title to real estate can be made more certain, please do not hesitate to contact me at jdemma@milesstockbridge.com