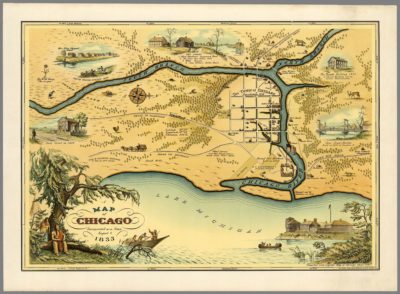

“Map of Chicago” published by Walter Conley & O.E. Stelzer, 1933, to commemorate the city’s centennial. Wikimedia

About a month into our pandemic lockdown was the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, an event its founders called a nationwide “teach-in on the environment.” 1970 saw the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and began an era of environmental legislation that transformed our landscape and society.

In the spirit of a teach-in, let’s look back to a time before modern environmental laws. In 1900, a lawsuit brought by the State of Missouri against the State of Illinois was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. While the boundary between the states, per se, was not in dispute, Missouri claimed that the crossing of that line by polluted water constituted a public nuisance.

The circumstances that led to that case involve a public health crisis, the growth of cities, and an engineering wonder that must have mobilized a battalion of surveyors. Part 1 of this article recounts a partial history of a nineteenth century waterway that connected the country, and Part 2 will discuss Missouri v. Illinois. Current environmental law will provide contrast, including an ongoing lawsuit by Native American tribes that captured worldwide attention (fitting for Native American Heritage Month).

Prehistory

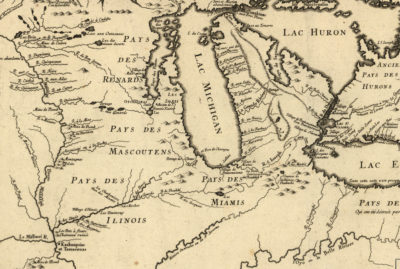

Detail from map by Jacques Bellin, “Partie Occidentale de la Nouvelle France ou du Canada,” 1755, showing Chicago Portage. The depiction and description of ruins and “Pots à fleurs” where the Illinois R. joins the Mississippi R. apparently refer to the resemblance to inverted flower pots of the abandoned Cahokia Mounds. Library of Congress

We begin at the end of the Ice Age, when the Wisconsin Glaciation that had carved out the Great Lakes retreated and filled them with fresh melt water. The glaciers left behind ridges of debris—geologic moraines—that still ring Lake Michigan and the outskirts of Chicago. The broadest of these is the Valparaiso Moraine, named after the town on that ridge’s loop around the lake.

Relevant to our story, this subtly elevated landform divides two natural watersheds. The area inside the loop empties into nearby Lake Michigan, while the outer watershed drains a huge swath of central Illinois into the Mississippi River via its southwesterly-flowing tributary, the Illinois River. This separation of ecosystems was the natural state before humans intervened.

Map of glacial features of Illinois and Indiana, based on Indiana Geological Survey. Chris Light/Wikimedia

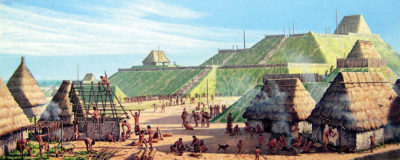

Since the earliest agrarian civilizations, rivers have equated with fertile land, transportation and trade. A thousand years ago, a teeming interregional marketplace, later called Cahokia, flourished at the union of three rivers: the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois (John Kelly, 1991).

Chicago Portage

Picture indigenous people journeying to Cahokia from Lake Michigan and points north on the highways of that time. Leaving the lake, they glide up the Chicago River and then portage their canoes across the moraine to a stream that soon forms the Illinois River. Centuries later, French explorers and fur-trading voyageurs also negotiated this overland divide, labeled “Portages de Chekagou” on a 1688 map by Venetian cartographer Coronelli.

Cahokia (ca. 1000-800 BP), painting by Michael Hampshire. Courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

Just as ancient cities depended on transportation to thrive, nineteenth century New York needed a waterway to exchange goods with the continent’s interior. In 1825, the Erie Canal linked the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, allowing New York City to claim its place as a world-class port. A similar channel in Illinois would complete the internal course from the Atlantic Seaboard to the Mississippi River Delta.

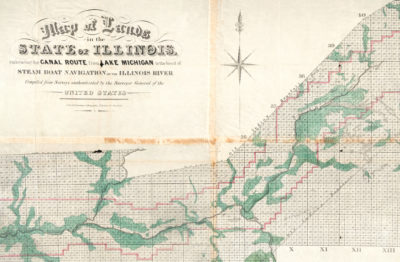

A canal through the Chicago Portage had been imagined a century and a half earlier by Louis Joliet. By 1816, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers moved toward its realization on lands of the Potawatomi, Chippewa (Ojibwe), Ottawa and other nations. Beyond the Army’s Fort Dearborn foothold at the mouth of the Chicago River, Major Stephen H. Long performed a topographic survey of the proposed canal route within a strategic 20-mile-wide strip of land “coercively purchased from the Indians” (Miller, 1996). Maps by the Surveyor General indicate “Indian Boundary” along this strip, whose traces remain on the streetscape in the angular Rogers Avenue and the names

of neighborhood parks.

“Map of Lands in the State of Illinois Embracing the Canal Route from Lake Michigan to the Head of Steam Boat Navigation on the Illinois River,” C.B. & J.R. Graham’s Lithography, 1835. “Old Indian Boundary” defines the original canal corridor. Courtesy of the Newberry Library

We are only touching upon the overarching government policy of Indian Removal. Integral to our story, in the first decades of Illinois statehood—and following skirmishes and conflicts over land between Native Americans and European-American settlers—the United States compelled local tribes to sell their ancestral lands and move west of the Mississippi. “This sordid transaction” formed “the legal basis” for the development of Chicago and the canal that would advance trade and settlement across the region (id.).

The I&M Canal

Along the 96-mile canal route towns were platted and laid out, including Chicago and Ottawa at opposite ends and Joliet in between. (James Thompson’s 1830 plat and surveyor’s compass are on view at the Chicago History Museum.) In 1848, mules began towing barges through the Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal, which was engineered with locks to navigate the 140-foot net gain in elevation from the Illinois River to Lake Michigan. The I&M Canal was the first cut through the Valparaiso Moraine, but it wouldn’t be the last.

With the canal and the advent of railroads, Chicago’s population jumped from less than 5,000 in 1840 to more than 100,00 at the start of the Civil War, to half a million in 1880. The rapid growth intensified public health conditions. In the canal’s first year, the city was struck by a deadly cholera epidemic caused by bacteria carried by an unwitting canal passenger (Vasile, NIU Lib.). Further outbreaks in the ensuing decades were precipitated by poor sanitation and contaminated water.

“For Succeeding Generations”

Could the I&M Canal have been built under today’s environmental regulations? The answer is: not so fast. A basic tenet of environmentalism is to anticipate and avoid adverse consequences, rather than react after harm occurs. Prevention is part of the value known as the “precautionary principle” (Rio Declar., 1992).

Preventing harm requires identifying risks, and the law creates a structure for this. A large public works project like a canal would be subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), signed into law by President Richard Nixon the same year as the first Earth Day. The law aims to “fulfill the responsibilities of each generation as trustee of the environment for succeeding generations.” (42 U.S.C. § 4331.)

The law carries out this purpose by requiring federal agencies to conduct an environmental review prior to taking certain “major Federal actions,” a term that includes private projects requiring a federal permit or funding. In addition to analyzing a project’s potential impacts on air, water and protected species, environmental review under NEPA also covers aesthetic topics (e.g. the effect on views of wind turbines) and cultural and historic resources (e.g. damage to ancient rock art after opening public lands to off-road vehicles). (40 CFR § 1508.8.)

Notably, NEPA does not compel the denial of projects based on their adverse impacts; the law merely strives for decision-making that is not oblivious to consequences. NEPA provides a forum, including public input, for identifying environmental concerns and considering less harmful alternatives.

River Reversal

Unabated filth in the streets of mid-century Chicago required action, which the city undertook with an elaborate project of sewer installation. The sewers managed the raw wastewater, however, by discharging into the Chicago River, which flowed into Lake Michigan, the source of the city’s drinking water. The system was ill-conceived and unsustainable.

To fix the problem and protect water quality, some “progressive health officials” pushed for enforcement of anti-dumping laws (Miller). Instead, the city opted for a “radical measure”: to repurpose the I&M Canal as a sewage channel. The plan entailed sending sewage away from the city, flushed by clean water from Lake Michigan. In 1871, the city modified the canal by completing a “deep cut” through the Valparaiso Moraine. The deepened channel obviated the particular locks previously needed to overcome that rise, and allowed gravity to reverse the flow of the Chicago River.

But in reality, the river was ineffectually sluggish such that it “appeared stagnant” (Ill. State Arch.). As a result, the canal amounted to an open “monster sewer” that afflicted downstate communities with “overpowering smells” (Miller).

Standing Rock, 2015-2020

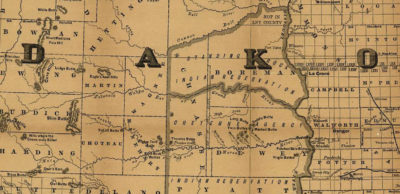

Detail from Railroad Map of Dakota by Rand McNally & Co., 1886, showing Cheyenne and Standing Rock Indian Reservations. Library of Congress

When Chicago resolved to send its wastewater downriver, no statute required the city to consider health risks. Today, in contrast, Native American tribes are engaged in a legal battle that presents NEPA in action in Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al. v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The case is linked historically to the 1848 California Gold Rush (the year the I&M Canal opened). To ensure safe passage for “forty-niners” on the Oregon Trail the United States and eight Indian Nations signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, which recognized vast Indian territories. Among their remnants are the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Indian Reservations in North and South Dakota.

The plaintiffs in Standing Rock are Indian tribes whose members live downstream from a company’s oil pipeline crossing the Missouri River. While the case raises larger debates such as reliance on fossil fuels, and involves environmental organizations, protesters, and two White House administrations, our focus here is on NEPA and judicial review.

The grant of an easement to allow the pipeline river crossing was the proposed “federal action” that triggered NEPA in Standing Rock. Accordingly, the Army Corps was required to make an initial assessment as to whether “significant environmental impacts” might result from the crossing. (Grand Canyon Tr. v. FAA (D.C. Cir. 2002).)

Under NEPA, if no such potential impacts are found, then after documenting its finding the agency may proceed without further environmental review. Conversely, if the agency finds that significant impacts might result from the action, then it must prepare a detailed environmental impact statement (EIS). This threshold determination by the agency is subject to judicial review.

Significant Impacts

The Tribes in Standing Rock challenged the Army Corps’ determination that the pipeline easement would have no significant impact after certain mitigation efforts, and therefore no EIS was required. Such decisions must be supported by more than “a cursory nod” to potential effects. The legal standard requires that agencies “take a hard look” at environmental concerns and “make a convincing case” for their conclusions. (255 F.Supp.3d 101.)

In 2017, the district court found that the Corps had inadequately considered, among other things, the impact of a potential oil spill on the Tribes’ rights to water, hunting and fishing promised by the Fort Laramie Treaty, and required the Corps to conduct additional analysis. Despite these flaws, the court did not cancel the easement or block the use of the pipeline through which oil had already begun to flow, citing the “possibility that the Corps will be able to substantiate its prior conclusions.” Since the analysis should have preceded the pipeline’s placement, the court warned against simply “treat[ing] remand as an exercise in filling out the proper paperwork post hoc.”

In 2020, the court rejected the Corps’ remand analysis and decision not to conduct further environmental review. The court found that “too many questions remain unanswered,” including “unrebutted expert critiques regarding leak-detection systems, operator safety, … and worst-case discharge.” (440 F.Supp.3d 1.) Regarding safety, the court said, “In this case, the operator’s history did not inspire confidence.”

The court vacated the easement, ordered the Army Corps to prepare an EIS, and ordered the pipeline shut down. A statement by the Tribe captures the value of NEPA: “[H]ealth and justice must be prioritized early … if we want to avoid a crisis later on.” The law gave the affected communities in Standing Rock a voice.

The Army Corps has appealed the ruling, and also sought an emergency stay of the district court’s orders. The Court of Appeals let stand the orders to prepare an EIS and void the easement, but allowed oil to continue flowing pending the appeal. (Case #20-5197, D.C. Cir. August 5, 2020.)

A Sanitary Canal for 1900

As the 1800s drew to a close, Chicago’s population swelled with a surge in immigration that would continue into the next century. (My grandparents were among that wave of Russian Jewish immigrants.) The city modernized and reinvigorated itself after the Great Chicago Fire, and made plans for a new canal to effectively deliver the city’s sewage downriver. This time, the State of Missouri protested. In Part 2 we will explore Missouri’s lawsuit.

Bibliography

Libby Hill, The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History (2016).

Illinois State Archives, Illinois and Michigan Canal, 1827-1911 [ilsos.net].

Donald L. Miller, City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (1996).

Lloyd Pilchen is a partner at Olivarez Madruga Lemieux O’Neill llp in Los Angeles and serves as legal counsel for cities and public agencies. He is a California and Illinois surveyor. Law Land Lines™ offers Lloyd’s reflections on the law.