The winds of curiosity have blown us to Jackson v. Dysling 2 Cai. R. 198 decided by the New York Supreme Court in 1804. We hitchhiked our way back here from Justice Cooley’s doings in the late 1870s. A good handful of cases have referenced Jackson v. Dysling and tied it to discussions of acquiescence and practical location. So, this just seems like a good place to spend some time.

The winds of curiosity have blown us to Jackson v. Dysling 2 Cai. R. 198 decided by the New York Supreme Court in 1804. We hitchhiked our way back here from Justice Cooley’s doings in the late 1870s. A good handful of cases have referenced Jackson v. Dysling and tied it to discussions of acquiescence and practical location. So, this just seems like a good place to spend some time.

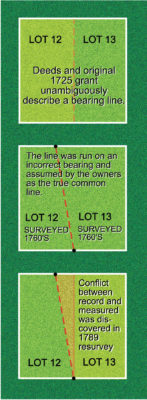

In 1725 partition deeds of the patent were issued. It sounds like we’re dealing with an original grant executed without a concerted survey but that’s not totally clear. Best I can tell the original and larger Harrison Patent of 5,000 acres preceded the deeds by five years. In the 1760’s coincidentally halfway between the original deeds and litigation the chainees in title hired a surveyor to mark the line. The line didn’t match the deeds because the surveyor did not allow for changes in magnetic declination. The owners took possession up to this line and held it through the time of litigation in 1804. The error became apparent a quarter of a century after the fact during a proper resurvey of the original deeds in 1789. That pretty much covers the rope stretching facts.

The owners met the IICBSISBS standard of care (If It Can Be Surveyed It Should Be Surveyed). There was no question about laying out the paper geometry. In fact, the 1789 survey isolated the field error made in 1760’s survey and raised a question that the owners could not resolve among themselves. Which line counts after the line was misdirected by a surveyor in the 1760’s?

The questions before the court are basically 1.) Does the 1760’s survey line hold up with 40 years of possession? 2.) Does the 1789 survey control under the defendant’s cheap talk to switch everything back when and if it’s convenient? 3.) Did the plaintiff have to prove that the convenient circumstances actually happened? So what’s the common denominator here? These are all questions of law.

The answer to “which survey is correct” became apparent two decades before this case hit Broadway. The court is not really looking at which survey is better but rather how the owners have behaved around the original grant and subsequent retracements. Each Justice carried a truly unique and perhaps original perspective. For what it’s worth the chain of title endured a monarchy, Articles of Confederation, and a newly adopted national Constitution.

Justice Spencer makes short work of his decision to “set aside” the verdict because the plaintiff didn’t prove that the defendant’s 1789 side deal materialized. However, he does opine that the 1760’s bum survey is “conclusive upon them” because the owners’ assented to it for a long period. He also felt “An agreement by parol, to the settlement of a line, appears to me effectual, and not liable to any objections on the score of the statutes of frauds and perjuries.” Spencer seems to recognize that the owners could waive the 1760’s the line in favor of the 1789 survey line but cautions that the second agreement is executory. In other words, the 1789 agreement is based on an “if-then” statement and the evidence does not show the outcome of the “if” part. So which survey line is right according to Justice Spencer? It sounds like he’ll buy any line the owners legally abide with.

Justice Spencer makes short work of his decision to “set aside” the verdict because the plaintiff didn’t prove that the defendant’s 1789 side deal materialized. However, he does opine that the 1760’s bum survey is “conclusive upon them” because the owners’ assented to it for a long period. He also felt “An agreement by parol, to the settlement of a line, appears to me effectual, and not liable to any objections on the score of the statutes of frauds and perjuries.” Spencer seems to recognize that the owners could waive the 1760’s the line in favor of the 1789 survey line but cautions that the second agreement is executory. In other words, the 1789 agreement is based on an “if-then” statement and the evidence does not show the outcome of the “if” part. So which survey line is right according to Justice Spencer? It sounds like he’ll buy any line the owners legally abide with.

Justice Thompson leads off with “The submission to two surveys, made by the lessor of the plaintiff and Jacob Klock, and their decision thereupon, cannot be considered as extending to the title of the land, or to have the operation of a conveyance”. We know retracement surveys are not conveyances. We also know that unwritten conveyances can happen under an operation of law. It sounds like Justice Thompson might be heading to the IICBSISBS camp on his decision.

Justice Thompson touches on the familiar concept that surveys are questions of fact not questions of law. “The title to lot No. 12 is admitted to be in the lessor of the plaintiff, and the submission was of a mere matter of fact, to ascertain where the line would run on actual survey, beginning at a place agreed on between the parties.” Then the Justice goes on to apply the facts to the law. Justice Thompson’s application is really well thought-out with respect to the title and survey world. The key here is the defendant’s behavior after the 1879 survey uncovered the 1760’s declination issue.

Remember the defendant’s “cheap talk” I mentioned earlier? In addition to being an unfulfilled promise, it also was an admission that he was encroaching. With regard to the defendant’s actions Justice Thompson opines “After, the line had been ascertained, and he knew where it run, he agreed to give up the possession and move his fence. Here was, then, a full and complete recognition of the extent and boundary of lot No. 12, to which it is admitted the lessor of the plaintiff has title.” So, when put on notice the defendant behaved with respect to the chain of title and accurate retracement of the original deeds. Justice Thompson continues “It is immaterial in what matter this line was ascertained, whether by a joint submission to one or more surveyors, or by an ex-parte survey; it is enough that Klock, after it had been ascertained, recognized it as the true line…And besides, this second agreement is not free from difficulty, on the ground of the statute of frauds. The title to the premises is acknowledged to be in the lessor of the plaintiff, and if the second agreement is to have any operation, it is to devest him of that title. Neither agreement can have the operation of changing the title; the first must be viewed as a waiver, by Klock, of all benefit resulting from length of possession, and opening the question as to the true line of division between the two lots, and the plaintiff’s title to the premises in question is shown, independent of either agreement. I am, therefore, of opinion that he is entitled to recover.” Again, we see these issues are matters of law.

Interestingly in Justice Thompson’s opinion the defendant uncorked any adverse possession claim and dumped that down the gutter. There is however a small detail in his opinion that I don’t think we can overlook. Remember, we’re unsure if there was a survey with the original grant. The Justice points out that the owners are empowered to agree on a fixed point. The Justice measures this opportunity with the law. “…the submission was of a mere matter of fact, to ascertain where the line would run on actual survey, beginning at a place agreed on between the parties. I cannot consider this agreement in any way affected by the statute of frauds.” So which survey line is right according to Justice Thompson? It sounds like he’s gonna plug n play this one and run the record deed description. This also feels like the most lawyer-esque of the three opinions and he employs the surveys as tools rather than solutions.

Justice Livingston feels the show is over and the monkey died four decades ago. He pulled out his judicial calipers and quickly measured the behavior of the owners with what he calls the first survey. “…it is not pretended that the plaintiff can recover; for the parties claiming these lots, having no less than forty years ago determined on the true line between them, by running the same, and having held their possessions accordingly ever since, no court would permit either of them, at this late day, to disturb the other. The defendant’s possession is not only adverse to the lessor’s claim, but commenced with his or his ancestor’s consent, and, therefore, ought not now to be questioned, merely on the ground that a mistake was made in the first survey.” So we see, right or wrong, the chainees in title have respected that old rubber needle survey. The force of the line is not in the surveyor’s opinion or precision but more with the owner’s behavior to the marks. Apparently in Justice Livingston’s eyes there are three qualities that make this line authoritative. One, the owners had the bent line professionally run on the ground, two, they “determined on” it being the true line, and three, they respected it for four decades. The devil in the detail is that the owners accepted it as the true line between them. Neither party intended to convey, receive or otherwise monkey with the title to Lots 12 and 13. They did make an earnest effort to establish and mark the common boundary of the lots. This doesn’t sound hostile or adverse. Now, I’m assuming that there was no original survey or the evidence was fully lost by the 1760’s, so take that with a grain of salt. Justice Livingston shores this up by saying “The defendant’s title must be regarded as complete at the time of the second survey, and to continue so still, unless he or his devisor has done anything to defeat it.” Justice Livingston definitely believes in letting sleeping dogs lie. He also forms a basis for holding possession over record. “…The defendant’s possession is not only adverse to the lessor’s claim, but commenced with his or his ancestor’s consent, and, therefore, ought not now to be questioned…”.

Ultimately a retracement of this boundary line hinges on a question of whether or not there was a transfer of title when the line was bent by 1760’s survey. I think Justice Livingston is saying “no transfer”, the line is the true line of 12 and 13. Title is not impacted so he would expect a retracement of occupation showing bent lines. Justice Thompson is also saying “no transfer” because the true line is over there at the record position and the defendant lost his adverse rights when he fessed up to the record line. He would expect our retracement to follow the original deed. Justice Spencer is saying “yes” there was a transfer by acquiescence to the “assented” 1760’s line. He would expect our retracement to follow the 1760’s survey and occupation.

Experience persuades the retracement surveyors to understand how the records fit the actual happenings on the ground. Chief Justice Thomas Cooley summed this up as good as anyone. “When a man has had a training in one of the exact sciences, where every problem within its purview is supposed to be susceptible of accurate solution, he is likely to be not a little impatient when he is told that, under some circumstances, he must recognize inaccuracies, and govern his action by facts which lead him away from the results which theoretically he ought to reach. Observation warrants us in saying that this remark may frequently be made of surveyors.” I reiterate Justice Livingston’s words “…having held their possessions accordingly ever since, no court would permit either of them, at this late day, to disturb the other…” and yet 2.165833333333 centuries later we’re still fighting over the same question. I wonder why?

The text for this case can be found at https://archive.amerisurv.com/docs/JacksonVersusDysling.docx