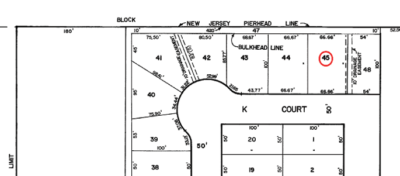

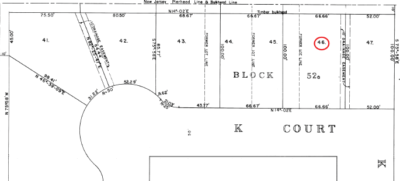

Subdivision Map: The Ralphs’ metes and bounds deed description refers to and circumscribes subdivision Lot 46 on this amended map for part of “Berkeley Quay.”

News stories often provoke thoughts about how we as surveyors can better “protect the health, safety, and welfare of the public” relying upon our expertise. Today’s relatively benign case (compared to some) arose when property owners were denied a permit for a dock extending into the Barnegat Bay along New Jersey’s coastline.

Before going any further, please don’t think this case doesn’t apply to you if your state doesn’t have oceanfront. The suit raised several universal points applying to any navigable waterway, to deed language, and to the linework depicted on our plans.

This story began in 2002 when James D. Ralph, III and his wife Diane purchased a property in Seaside Park platted as Lot 46 of the “Berkeley Quay” subdivision as amended in 1968. Five years after their acquisition, the Ralphs filed an application with New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection for a waterfront development permit that would allow them to build their desired dock 60 feet from the wood bulkhead through a soon-to-be contested 10-foot wide area.

Because of their impact on this case, we will start by addressing pierhead and bulkhead lines. Speaking generally, these are legal limits to upland owners’ rights to extend into water in order to protect public rights of navigation and commerce, with those physical limits under the jurisdiction of the Army Corps of Engineers. (See 33 USC §401 et seq., particularly §404.)

The pierhead line is the limit (by determination of the Army Corps of Engineers) to which any construction or fill can extend into tidal and/or navigable waters without obstructing commerce and navigation—and then only by permit from the appropriate regulating entity.

While bulkhead lines have slight variations in definition in the States, in the case at hand where New Jersey tidal waters are involved these are the limits of dry land and also an upland owner’s private rights, as the bulkhead keeps out tidal waters that could create public rights in lands now or formerly flowed by the tide.

Returning to the Ralphs, after being denied a permit to build through and beyond it, they contended that they owned to the watery far side of the 10-foot wide strip beyond the bulkhead line. Seaside Park Borough claimed deeded ownership of the 10-foot strip, which would prevent the Ralphs from building over it. Setting aside the Ralphs’ contention that the deed from the last remaining stockholders of the then defunct development company to the Borough was void (it was not), they presented other arguments relating to solid and dashed lines on the subdivision plan. The bulkhead line appears as the solid rear line of their platted Lot 46, while the “N.J. Pierhead Line” in Barnegat Bay is dashed.

Experts testified about the use of solid versus dashed lines on both the original and amended plans, because the Ralphs also pointed out that the solid sidelines of the subdivision lots appear to extend to the dashed pierhead line, leading them to believe that they owned beyond the bulkhead line to include the part of that strip abutting their lot.

Typically, solid lines indicate property boundaries while dashed ones indicate other interests. But the linear dimensions on the subdivision and in the Ralphs’ deed (the first to include metes and bounds rather than simply reference to the subdivision plat and/or tax map) and even the tax assessment for their property indicate exclusion of that 10-foot wide strip. The trial court judge also noted (as underscored by the appellate judge) that “there is no reference to the tide-flowed land in any of the deeds in the plaintiffs’ chain of title, and the deeds do not mention riparian lands, tidelands, submerged lands, subaqueous lands, or the Pierhead Line.”

The tax map has morphed a bit over the years, but has always shown a ten-foot wide strip as separate from the subdivision lots. After that strip was sold to Seaside Park by the remnants of the development company, it became a separate single tax lot (Lot 47). With their deed descriptions of the conveyed lands by subdivision and tax map references, the Ralphs’ predecessors apparently never believed they owned or could pass title to the now disputed riparian strip.

So—lessons learned? (1) Be careful about jurisdictional waters, and be familiar with your state’s laws relating to lands near bulkhead and pierhead lines so they can be explained to clients. Federal regulations may also apply to protect wetlands, commerce, and navigation. (2) Be careful about graphic depictions on your survey and subdivision documents. Professional colleagues will not be the only ones perusing them, and one of Murphy’s Laws says that anything that can possibly be misconstrued will at some point be misconstrued. (3) Surveyors are not the final drafters of deeds, although we supply descriptions with “subject to” and “together with” clauses. Sometimes someone else retypes our descriptions into the deed, leaving out those extra clauses. Consequently, we cannot guarantee that all relevant conditions are revealed in the recorded deed. Our fallback is to make sure to note those conditions on all documents, particularly survey and subdivision plans, to make it more likely that full disclosure does occur.