USLM No. 2 in the St. Joe Mining District of Idaho was placed on this advantageous point along the Idaho/Montana border in 1903. The “Lucky Dutchman” claim (MS 1890) is located approx. one-half mile to the southwest.

The growth of nearly every civilization can be linked to the discovery, development, and application of its precious metals and natural resources. Since the early populated areas of the United States generally advanced from east to west, so came the need for surveying the land. Notable early disruptions to this natural progression were the discoveries of gold in California in 1848, the Pike’s Peak region of modern-day Colorado in 1858, silver in Nevada in 1859, the Montana and Idaho rushes of the 1860’s, and the Black Hills rush of the late 1870’s in Dakota Territory.

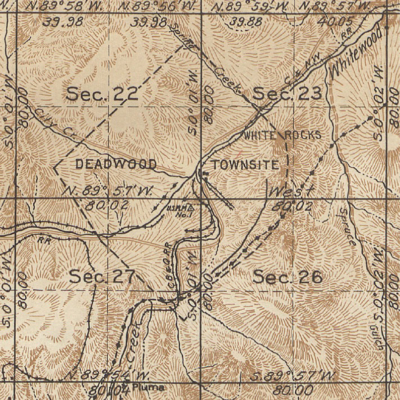

USMM No. 1 in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory was established in 1877 on Deadwood Peak. Many mineral surveys, including those for the famed Homestake Mining Company, tied into this point for several decades before the GLO tied it into the PLSS.

Development of these resources necessitated the need for establishing and surveying mineral claims to protect the rights of those who made the discoveries. Without changing the plan of the advancing surveys, it could take years or even decades before the Public Land Surveys would reach these areas.

USLM No. 3554 for Mineral Survey No. 3554 in Montana was established in 1891 for the “Silver Crest Lode” in the Boulder Mining District.

To solve this dilemma, either a new meridian and baseline had to be quickly established or the mining claims had to be surveyed as separate tracts and tied into the system later. Because mining operations occurred immediately in these areas, the latter was often implemented as the best solution. The General Land Office devised a process where the mineral surveys would be tied into a local point known as a “Location Monument” or sometimes referred to as a “Mineral Monument”. These monuments were usually designated USLM or USMM.

This square nail (above) is likely the tie-in point on USLM No. 54 near Silver City, Dakota Territory. It was placed in 1887 during the survey of the “Nebraska Bar Placer” claim (MS 504).

The site for the location monument was generally upon a prominent point preferably visible from other directions and in a safe area so the permanency of the monument would not be endangered by snow and rock landslides or other natural causes. Early instructions specified Corner No. 1 of each mineral survey was to be connected by course and distance to the nearest location monument if the claim lied within one mile of an established monument. If none existed within the required distance, then a new location monument was established.

Gary Little of Montana, reveals the chiseled scribing on a large rock that reads “I. P. Boulder Mon. 1”. This was Initial Point No. 1 in the Boulder Mining District of Montana when the “Princeton Lode” was surveyed in 1885.

A detailed description of the location monument and sometimes a topographical sketch of its locality accompanied the mineral survey notes sent to the Surveyor General’s office. From the location monument, bearings and distances were to be taken to two or three nearby bearing trees or rocks. Bearings were also taken to prominent mountain peaks and the approximate distance and direction was given from the nearest town or mining camp. This information assisted the Surveyor General in determining within which townships the location monuments were placed when the public land surveys arrived later.

The initial instructions regarding mineral surveys were issued by the respective surveyor generals within the state where the surveys were being performed. This resulted in some differences in the manner in which the location monuments were described and numbered. The exact number of specific manuals that were issued for mineral surveyors is uncertain. Those known to exist are for the states of Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, and Utah variously between the years 1883 and 1894.

In the preface for the 1890 Montana manual, George O. Eaton, U. S. Surveyor General, mentioned an “old manual”, issued in 1884, had become obsolete with the issuing of various circulars and orders. This manual also mentioned the location monuments had formerly been known as “Initial Points”. The 1890 Manual further stated the location monuments in Montana were now to be marked “U.S.L.M.” along with the number identical to the survey for which the monument was established. Mineral Survey No. 4107, would therefore be tied into newly established USLM No. 4107 if it was the first survey in the area.

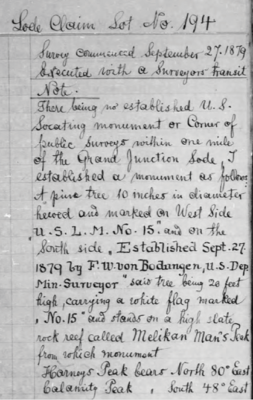

U. S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor Frederick W. Von Bodungen describes the point he established for USLM No. 15 in 1879, by using a standing 10” diameter pine tree. The “Grand Junction Lode” (MS 194) is near present-day Custer, South Dakota.

There were twelve U. S. deputy mineral surveyors at work in the Black Hills region of Dakota Territory in 1882. Filed notes as early as 1889 state the surveys were being done “in accordance with instructions for the Dakota District”, indicating there was an early manual issued for the Dakotas. There were as many as sixteen different mining districts in the Black Hills, but the location monuments were never repeated in number. This region had at least 97 different location monuments that were established between 1876 and 1903. Colorado and other states, however, established location monuments with the same number if they were located in different mining districts. The Surveyor General’s Office was most likely keeping track of each monument as it was established, however, ledgers specifically listing only the various location monuments are not known to exist.

In 1895, the GLO issued the first standardized “Manual of Instructions for the Survey of the Mineral Lands of the United States” that was to be used in all states where mineral surveys were being performed. This manual was reissued in 1897 and again in 1909. The 1909 manual stated the latitude and longitude for each new location monument should be determined as accurately as the instrument being used would permit. This was the last manual that was separate from the main Manual of Instructions to surveyors. Subsequent manuals only included chapters on mineral surveys.

USLM 3654 (above) was established in 1887 for the “Meta Lode” (MS 3654) in the Helena Land District of Montana.

Before the instructions for mineral surveys were standardized to specifically state what should be placed for location monuments, the mineral surveyors were marking rocks, scribing trees and posts, or placing various items such as drill bits from nearby mining operations. The 1895 Manual stated if the location monument was to be placed upon solid rock, a cross with lines 6 inches each way should be chiseled one-fourth of an inch deep. Otherwise, a six-inch-square wood post, 8 feet long, with 3 feet set into the ground along with a conical mound of stone 3 feet tall with a 6-foot base surrounding the post should be used. The initials U.S.L.M., along with the monument’s number, were to be cut into the rock or post with letters 3 inches tall. There was no objection to establishing monuments of a larger size or of material more durable. The chiseled cross on the rock would mark the exact tie-in point, or if a post was used, a tack or nail was driven to indicate the point. Some surveyors continued to use a variety of monuments and removing the lower branches of a tree and scribing it for the location monument was a favorite.

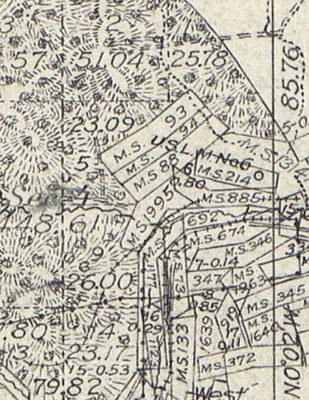

A myriad of mining claims (right) surround USLM No. 6 that was established in 1878 for the silver mines at Galena, Dakota Territory.

The field notes for the mineral surveys generally stated a single bearing and distance to the location monument from the initial corner of the survey. The plat, likewise showed one single line from the initial corner to the location monument. Since trees typically existed in the mountainous areas where the mineral surveys were performed, the surveyor often had to traverse to the location monument and then compute the straight line bearing and distance from it to the initial corner of the survey. The traverse or straight line connecting the mineral survey to the location monument had to be actually measured during the survey and could not be mathematically calculated through connections with other mineral surveys unless the lines of those surveys were first retraced for accuracy.

When the Public Land Surveys reached these areas, the location monuments were tied in to the nearest section corner by direction and distance. This ensured the individual mineral surveys could be mathematically tied into the overall public land system. Finding and tying in the location monuments into the system was undoubtedly a challenge for the deputy surveyors who were subdividing the townships where one was known to exist. The Surveyor General only provided the general topographical location where the location monument was supposed to exist which required the deputy surveyor to deviate from running his lines and make a thorough search.

Today, many of these important and early historic monuments have long disappeared. Most surveyors who have never worked in areas where the mineral surveys were performed are not familiar with location monuments. These monuments were an interesting aspect of the western surveys that provided a means to get the mineral claims surveyed in remote areas of the country without delay.