This appropriately named street in St. George, Utah is a little drier than it was a few minutes before, when it was completely under water during a sudden ten minute downpour and it was too wet to get a good photo.

I am just back from a hiking vacation in Moab, Utah, visiting Arches National Park and Canyonlands National Park and marveling at the visual history of how our planet formed through deposited layers preserved as they turned to stone. It is amazing to see evidence of the former inland seas, with coral and fish fossils up there at elevations between 4,000 and 6,000 feet above current sea level. It was easy for me to understand the soils in this context, but I’m not sure the general public understands how a place like this can be prone to flooding.

In the parks, the rangers warned of areas to avoid if it even vaguely looked like rain. The hard packed soils and high (or exposed) bedrock would quickly flood, and canyon trails could be deadly.

The Moab skies were cloudless most days, but a few evenings featured some short but heavy thunderstorms (bringing the temperature down below 103). Our next hikes showed us water-filled depressions and wet marks indicating how high the water had reached on some of the rocky walls lining the trails. This is flash flood country.

What does that mean? The National Weather Service defines flash flooding as “flooding that begins within 6 hours and often within 3 hours of heavy rainfall (or other cause).” NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory further describes flash flooding as combining “the destructive power of a flood with incredible speed and unpredictability.” To understand this hazard, we need to pay attention to several factors: the intensity of the rainfall, the duration of the rainfall, and the topography, vegetation, soils, and impervious surfaces in the area. Flash flooding happens so quickly that people are generally unable to respond in time to get out of its way.

I recall driving on a highway in southern New Mexico a few years ago when the sky suddenly loosed so much water from the black clouds overhead that visibility plummeted to zero, and the few cars on the road all pulled over to the highest points we could find. Despite a deep drainage ditch in the median, within just a few minutes the highway was under about four inches of water. Luckily the storm was less than ten minutes long, or we could all have been swept away; it takes only 12 inches to float most cars (and about six inches to reach water-incompatible mechanical and electrical parts on their undersides).

It is difficult to explain the dangers of flash flooding to people who think it can’t happen to them. While we might recognize that urbanized areas with lots of impervious surface have some likelihood of flooding, any area with steep slopes can be subject to rapid runoff and elevated waters as a result. Inlets will be overwhelmed, streams will quickly rise, and in areas with constricted flow (urban or rural), water levels can suddenly increase many feet. Areas that have experienced wildfires are particularly prone, as intense heat creates a chemical reaction that seals soil from being able to absorb moisture, like a glaze. Flash floods occur because soils cannot absorb water as fast as they are receiving it.

On our way out to Moab, we had stopped in St. George, Utah, where the weather turned suddenly dark and torrentially wet. The street scene image shows the aftermath of a ten minute storm after a blazingly hot, dry day. I could not resist taking a photo of an appropriately named street with an unintended paved river running down its center and overflowing gutters racing like rapids more than a foot deep.

Meanwhile, back home on the East coast it was thunderstorm season, and both my county and a few other areas made the news on receiving mass quantities of water over a short period of time. The next township over from mine has requested Pennsylvania’s governor to ask for a presidentially-declared disaster so that recovery funds might assist the many wiped out businesses and damaged homes. A little further east, my brother’s township experienced 8 inches of rain in a day. Since during Superstorm Sandy the water had come within inches of his home’s slab on grade foundation (but inundated his neighbors up to 4 feet), I was concerned. Once again he was fine, but a main intersection half a mile away was underwater and residents in a nearby retirement development had to be evacuated by boat.

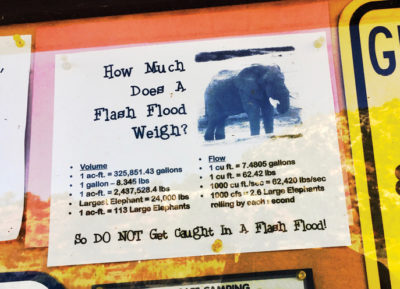

A sign meant to be an attention grabber in Escalante’s Petrified Forest State Park: While not native to the US (mammoths having disappeared long ago), most of us can understand comparisons to modern elephants.

How much does a flash flood weigh? That may seem like a silly question, but sometimes it’s necessary to be silly to catch people’s attention. In Escalante, Utah’s Petrified Forest State Park, the bulletin board on the side of the campground restroom contains the usual warnings about keeping food locked up and away from bears, but also warnings about avoiding the dangers of flash floods—in terms of elephants. Starting with an explanation of the weight of gallons and acre-feet of water, we are logically brought to the understanding that one acre-foot has the volume of 113 large elephants. Flow is explained in cubic feet and pounds per second, culminating in the calculation that “1000 cfs = 2.6 Large Elephants rolling by each second.” The moral appears in large font at the bottom of the sheet: “So DO NOT get caught in a flash flood!” That’s good advice for all of us.

A PDF of this article as it appeared in the magazine is available by clicking HERE