This month’s case takes us to the State of Maine and I think the internet is broken. I googled the most famous person from Maine and I was floored to find that it wasn’t Knud Hermansen. Some guy named Stephen King topped the list. I guess Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was correct when he said you can’t believe everything you see on the web. Go figure, and I bet this King fella couldn’t even survey his way up an old tote road?

This month’s case takes us to the State of Maine and I think the internet is broken. I googled the most famous person from Maine and I was floored to find that it wasn’t Knud Hermansen. Some guy named Stephen King topped the list. I guess Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was correct when he said you can’t believe everything you see on the web. Go figure, and I bet this King fella couldn’t even survey his way up an old tote road?

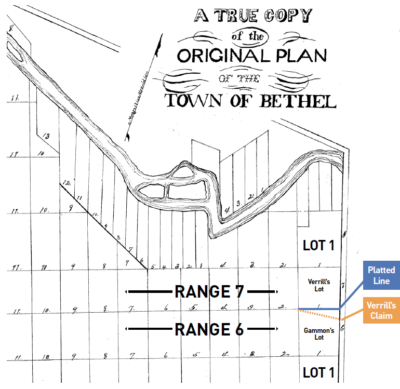

This case was appealed by the plaintiff after the superior court ruled against him. The superior court relied on expert testimony that supported what appears in hindsight to be a practical location of the line. I quote the Supreme Court “…the (superior) court could have determined the approximate location of the range line based in part on the Original Plan of the Town of Bethel. The original plan is not drawn to scale, but it lays off the range lines. Several town plans were introduced into evidence, none of them identical, but they all have one feature in common: the range lines are parallel to the southern boundary of the town. The range line, as located by the (superior) court, deviates 21° from the bearing of the southern boundary of the town. The (superior) court erroneously discounted the usefulness of the original plan so far as that plan established that the range lines are parallel to, and on the same bearing as, the southerly boundary of the town.” Just a few housekeeping items to mention: In this case the ranges run 90° to the contemporary BLM schematic. So, we are talking about a line that actually runs east & west. The subject lots are more akin to contemporary sections rather than 25′ x 100′ town lots. Laying them out would be more synonymous with the term “adventurous” than it would be with today’s visions of “lot staking”. I suspect these lots are a magnitude of “tens” of chains measured through some rugged woodlands. Also, I jump between “Superior” and “Supreme” frequently. My apologies and my hope is that I’m at least clear which court is being referenced.

The Superior Court smoked out the following evidence. “The expert witnesses agree that a 1949 survey marker, located at the southwest corner of defendants’ property and the northwest corner of Gammon’s property, marks the location of the range line on the western side of the parcels (point ). The present controversy concerns the course of the range line east of point as it traverses lot 1. Gammon claims that the range line bears approximately east 10° north from point to the Bethel Rumford town line. The range line asserted by Gammon has the same bearing as the range line of the adjacent lot and the southern boundary of the Town of Bethel, and is parallel to the range line between range 7 and 8. Defendants claim the range line bears approximately east 10° south from point to a post marked 1909 on the Bethel Rumford town line.” It was additionally stated that the evidence provided no original surveys or monuments. There was testimony discussing a rotation of bearings presumably due to a natural change in magnetic declination. “The southerly boundary of the Town of Bethel, as established by the Massachusetts General Court in 1796, was east 20° north. See 1796 Mass. Acts Ch. 3. The declination for Oxford County has increased 8° 15′ west since 1796. Thus the southern boundary of Bethel today bears east 11° 45′ North. Gammon’s surveyor testified that the course of the range line is east 11° north. Correcting the southerly boundary of Bethel for the change in magnetic declination, the bearing of the surveyor’s range line is within 1° of the bearing of the town’s southerly boundary.” This really is not a contentious feature of this case. It’s worth a mention because it demonstrates how seamlessly the testimony of a competent professional can flow. I suppose it doesn’t always happen this way but in this case it uneventfully found its way into the record.

I suspect the lower court did what it was supposed to do when it respected the surveyor’s opinion of the line based on common report. “The (Superior) court agreed with the defendants, finding that the boundary between the defendants’ and the plaintiff’s property ran from point to the 1909 survey marker.” However, I may be overstepping when I think that the superior court established this boundary by practical location. Remember, there was no evidence of original survey or monuments, so we could be looking at a lower court acknowledging a “first monuments” scenario. It may seem a bit out of context but for more info on “first monuments” see “Arizona Surveying and Boundary Law” page 272 in the “Analysis” of Chapter 12 found at Maricopa County (AZ) DOT Website www. maricopa.gov/601/Related-Survey-Resources. Regardless of applicability here, the “first monuments” concept is noteworthy in general retracement work, so take a peek. Okay, back on point, The Supreme Court showed up dangling their bobs in accordance with the plat and said this: ” Because the evidence provided neither original surveys nor original monuments the (Superior) court relied solely on usage in locating the range line. The trial court’s location of the range line was clearly erroneous….It is clear from this record that the range line must be approximately parallel to the south line of the town. The evidence including the survey locating the range line west of point , aerial photographs and defendant’s own exhibit showing the range line between range 7 and 8 all establish that the range lines are parallel. Moreover, both parties’ surveyors testified that the range lines in the Town of Bethel are parallel to its southern boundary. Evidence of usage as well as evidence of the marker erected on the east line in 1909 are insufficient, as a matter of law, to overcome the undisputed evidence of the bearing of the range line. Applying that bearing from point , the range line can be located without resort to evidence of usage. This would establish the range line where Gammon asserts it is located. The entry is: Judgment vacated.”

The Supreme Court challenged the evidentiary value of the post as noted above having found nothing to tie it to an original survey and that’s the big deal breaker here. Courts have repeatedly pointed out how important it is for the surveyor to relate the existing evidence to the original plat. See (Dittrich v. Ubl 216 Minn. 396 Dec 2016 TAS) and (Erickson v. Turnquist Feb 2017 TAS). Have you ever ordered food only to have a waitress bombard you with a gazillion questions and options? You simply want to fill your belly and dinner is not a complicated affair, so you say “I don’t care, just give me the picture on the menu.” I think the Supreme Court did a similar thing with the map geometry. That’s what was offered, that’s what we expect. So ask yourself “does it look like the picture?”… and there you have it in the Great State of Maine. Feel free to send feedback to me at rls43185@gmail.com or to the editor.

Sidebar:

The Barbershop Barrister

The Supreme Court’s decision in Gammon v. Verrill is concise. I like that. The Court wasted no time or effort in figuring out they needed to do some surveying to settle this matter. I quote the Court. “In boundary disputes, what the boundaries are is a question of law, but where the boundaries are on the face of the earth is a question of fact. Liebler v. Abbott, 388 A.2d 520, 521 (Me.1978) (quoting Rusha v. Little, 309 A.2d 867, 869 (Me.1973)); Perkins v. Jacobs, 124 Me. 347, 349, 129 A. 4, 5 (1925); Abbott v. Abbott, 51 Me. 575, 581 (1863). This case does not involve a dispute as to the legal boundary in a deed; rather, it involves the factual question of where the boundary is located. The trial court’s factual finding will not be disturbed on appeal unless it is clearly erroneous. Liebler, 388 A.2d at 522.” The reliance on Lieber v. Abbott apparently does two things here. For one it separates title issues from survey issues, and for the other it provides the Supreme Court with precedent to hear this appeal and overturn the Superior Court’s decision. Our role obviously centers around the facts relating to the rope stretching and “where” question.

Okay, so the Supreme Court figured out it’s a survey deal and why they can grab the reins from Superior Court. This is where I think something really slick happened. The Supreme Court appropriately used the law to invalidate the opinion of Superior Court and further to demonstrate how the Superior Court failed to meet the standard of care. The Supreme Court said “Because the evidence provided neither original surveys nor original monuments the (superior) court relied solely on usage in locating the range line. The trial court’s location of the range line was clearly erroneous.” Am I the only one who thinks this is a big deal? It sounds like the Superior Court was suggesting a practical location, doesn’t it? What else can you do without original monuments? The Superior Court and the defendant tried to make sense from the ground evidence. Verrill’s surveyor apparently held a monument by or with common report. These are good faith attempts and respectable. However, as the Supreme Court pointed out, we really have to make a leap of faith to establish this as the true corner without any direct pedigree to the original plat. I suspect that the fact the post was some twenty degrees out of place is probably subordinate to the apparent absence of a connection to the original map. Original monuments would control regardless of errors, right? Sounds easy enough and works well in old T-Jeff’s PLSS but there might not be original monuments to find in Bethel. I recall Wacker vs. Price (see TAS. May 2017) examining a plat that was subsequently laid out without the benefit of original monuments. Just a quick offhand note: I’m loosely using the term “practical location” throughout the article and taking that with a big grain of salt, maybe even an aspirin or two. Feel free to spout off if you know better.

So now I have a few questions. What evidence lead Verrill’s surveyor to a find a post where it’s not supposed to be in the first place? Was it the owner’s arbitrary assumption that the post was his corner? What was the basis of the 1909 survey that recognized the post? Why is one end of the line from 1949 and the other from 1909? How are any of these concerns related to the original plat? These are real questions in retracement work and may have solid answers that just didn’t quite make it to the record. On that note, let’s all join hands for this month’s “TAS Moment of Clarity”: If the record does not lead you there, ask yourself if you belong there? If your answer is “yes”, then what evidence do you have to tie the original survey and map to that place?

There’s more to this than just measuring or stumbling across posts. Recovering the pedigree of a monument, recognizing prior bona fide retracements and realizing harmonious occupation with an original survey map are all spokes in our wheel. So back we go to that question of “what else can we do without original monuments?”

The Supreme Court really hauls in the big marlin and provides us guidance when they go back to the original plat. If you recall our panel of Surveyors in Crow Wing County (See Halverson v. Deerwood Village TAS Feb 2018) struggled with challenging dimensions and deemed a plat useless for that sake. If you thought the Deerwood plat (Halverson) was a challenge then take a peek at the Bethel town plat in this case (see image included in article). It looks like a stark naked chess board had a drunken soiree with the shingle diagram of a shake roof. Regardless, the Supreme Court of Maine does the opposite of the “Halverson Panel” here and embellished the state motto “Dirigo”. The Supreme Court didn’t look at what was missing from the plat but instead embraced what they actually had to work with. When they couldn’t find angular minutia or geometric precision they simply stepped back and saw rectangles and parallel lines. This is how it’s done when you can’t see the forest through the trees. And another thing, I have yet to run up against a case where the Court throws out the plat and calls a mulligan. I suppose there’s a few out there but it seems like courts do everything in their power to respect and implement a plat or deed description. Even when a practical location is employed it still carries the record description, right? So here are a few questions for the readers: When a practical location is fully validated and employed by the court, does it maintain its simultaneous weight with the rest of the plat or does it take on a sequential nature? Is a senior right of a deed surrendered in a boundary line agreement? Now hold your horses folks, those are some good examples of “what a boundary is” rather than a question of “where it is”. I’m going to have to call in a lifeline. Would somebody get Knud Hermansen on the blower…

Note: A special thanks to Kelly Bellis, PS, of Ellsworth, Maine for pointing me to the Oxford County Recorder’s website and MEGIS (Maine GIS). Harvesting colloquial knowledge from the local experts is an enjoyable benefit of our profession.