Since the fabled rope pullers in Egypt laid out parcels of land alongside the Nile River, to modern Land Surveyors with GPS marking out boundary lines, surveyors have been placing markers in the ground for centuries. Those set by government employees are protected under federal law and are owned by the federal government. Title 18 U.S.C. 1858, provides a penalty for the unauthorized alteration or removal of any Government survey monument or marked trees: “Whoever willfully destroys, defaces, changes, or removes to another place any section corner, quarter-section corner, or meander post, on any Government line of survey, or willfully cuts down any witness tree or any tree blazed to mark the line of a Government survey, or willfully defaces, changes or removes any monument or bench mark of any Government survey, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than six months, or both.”

When a private Land Surveyor creates a subdivision map and sets lot corners and the lots are sold, who owns those monuments? If in the street, perhaps the city or county but, if in the back yard, who owns those? When a Land Surveyor is hired to reestablish a boundary line and sets monuments, who owns them? Perhaps the survey of a metes and bounds description is the first time anything was set in the ground? What rights, exactly, does a Land Surveyor have to place objects in the ground of private property? Does it matter if the surveyor is a private employee or government employee? A recent case in California sheds some light on this topic, although in ways no one expected.

When a private Land Surveyor creates a subdivision map and sets lot corners and the lots are sold, who owns those monuments? If in the street, perhaps the city or county but, if in the back yard, who owns those? When a Land Surveyor is hired to reestablish a boundary line and sets monuments, who owns them? Perhaps the survey of a metes and bounds description is the first time anything was set in the ground? What rights, exactly, does a Land Surveyor have to place objects in the ground of private property? Does it matter if the surveyor is a private employee or government employee? A recent case in California sheds some light on this topic, although in ways no one expected.

The conflict involves land located along the 196-mile long Santa Ana River, the largest waterway located entirely within Southern California. Beginning high atop the San Bernardino Mountains, the oak-lined waterway flows through Riverside and San Bernardino Counties before reaching Orange County where it drains into the Pacific Ocean, south of Huntington Beach at the legendary shores of Surf City USA.

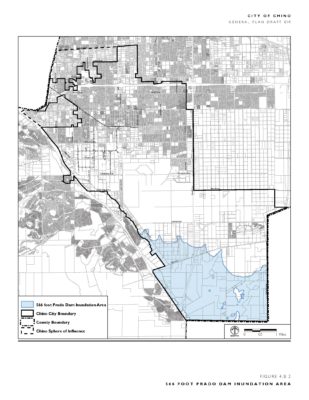

Following an influx of Americans after the turn of the last century, the properties adjacent to the river began to develop, and the sinewy watercourse drew the attention of the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1936, the United States government built a massive earthen dam to both store water and to prevent flooding. Two years later, and as if on cue, the river breached its banks and killed fifty people and countless livestock, leaving in its wake, a vast reservoir. In 1941, the federal government erected a more substantial structure and named it The Prado Dam, an appellation derived from the days of Spanish occupation when the countryside was known as a “prado” or meadow. The mammoth edifice was one of six government dams built in Southern California during the Great Depression. Upon completion, the structure gave birth to the Prado Dam Flood Control Basin, fixing the lines of inundation at an elevation of 556 feet above mean sea level.

In order to secure the land necessary to accommodate the new boundaries, the federal government filed a condemnation action. A second action was brought in 1945, expanding the area, resulting in the recordation of a new and expansive easement. Under the terms of the burden, the government acquired “[a] flowage easement consisting of flowage rights, to the right to prohibit human habitation and a permanent easement vested in the United States of America, to flood and inundate the property… whenever and wherever the control of storm water runoff in the Prado Flood Control Basin required such flooding and inundation…”

In order to secure the land necessary to accommodate the new boundaries, the federal government filed a condemnation action. A second action was brought in 1945, expanding the area, resulting in the recordation of a new and expansive easement. Under the terms of the burden, the government acquired “[a] flowage easement consisting of flowage rights, to the right to prohibit human habitation and a permanent easement vested in the United States of America, to flood and inundate the property… whenever and wherever the control of storm water runoff in the Prado Flood Control Basin required such flooding and inundation…”

As part of the ongoing efforts to further control the river and conserve water, in 1980, the Army Corps of Engineers and Orange County decided to raise the inundation line from 556-feet to 566-feet by constructing new levees and dikes necessitating the acquisition of more than 2,300 acres of property rights for reservoir expansion increasing the reservoir area from 6,695 acres to 10,256 acres while increasingimpoundment from 217,000 acre-feet to 362,000 acre-feet. The project was estimated at a cost of $880 million which included raising the existing embankment 28 feet to an elevation of 595 feet. As part of the deal, the federal government assumed the responsibility to acquire the land either by purchase or condemnation.

Over the years, the area continued developing as fertile agricultural land and eventually, portions of it were acquired by the Steuve Brothers Farms and others including the Land O Lakes Dairy and Alta Dena Dairy, purveyors of fine milk, cream, cheese, butter, and eggs. Despite the location of the properties in a designated flood basin, none of them ever flooded. In 1991, the Orange County Environmental Management Agency commissioned Irvine, CA based J. P. Kapp and Associates to survey the revised limits of inundation, based upon criteria “supplied by the Army Corps of Engineers.” The purpose of the survey was “to determine the limits of acquisition of real property rights required for enlarging Prado Dam.” On the recorded survey, the line was marked “Proposed Limit of Dam Reservoir.” Chief surveyor Leonard Charles Stiles set six iron pipes, two-feet below grade, centered with 3-5/8″ brass disks, demarcating the line marked thus:

Over the years, the area continued developing as fertile agricultural land and eventually, portions of it were acquired by the Steuve Brothers Farms and others including the Land O Lakes Dairy and Alta Dena Dairy, purveyors of fine milk, cream, cheese, butter, and eggs. Despite the location of the properties in a designated flood basin, none of them ever flooded. In 1991, the Orange County Environmental Management Agency commissioned Irvine, CA based J. P. Kapp and Associates to survey the revised limits of inundation, based upon criteria “supplied by the Army Corps of Engineers.” The purpose of the survey was “to determine the limits of acquisition of real property rights required for enlarging Prado Dam.” On the recorded survey, the line was marked “Proposed Limit of Dam Reservoir.” Chief surveyor Leonard Charles Stiles set six iron pipes, two-feet below grade, centered with 3-5/8″ brass disks, demarcating the line marked thus:

FOR L.A. DISTRICT U.S. ARMY CORP

OF ENGINEERS AND COUNTY OF ORANGE

BY J.P. KAPP AND ASSOCIATES, INC.

LS 5023

566 FOOT INUNDATION LINE

For reasons that remain unclear, there was no explanation as to why Stiles placed the monuments, in the ground, precisely two-feet deep. In doing so, more confusion was added as it was unclear if the monuments were fixed at the prescribed elevation of 566 feet or, alternately if they were on a different datum or, perhaps the stamped elevation was irrelevant. Unfortunately, the recorded survey is silent as to what was intended (See Riverside County Record of Survey recorded on February 5, 1993, in Book 97, Pages 8-18). Regardless of the reasons, because the stamped pipes were buried so deep, it made them impossible to find or observe. They were hidden monuments and, again for reasons that remain troubling, the property owners were never notified about the survey. Over the intervening years, Orange County offered to purchase the Steuve property for $9,000,000. Stueve countered with an unacceptable offer of $21,595,579 leading to shuttered negotiations.

GIS overlay of Record of Survey Map. The described easement covers numerous developed parcels and many public roads.

In 2003, the federal government entered into another agreement with Orange County to raise the Prado Dam by 28-feet, as part of the Santa Ana River Main Stem Project. The Stueves meanwhile submitted development plans for a high density, mixed-use development. The Corps agreed not to oppose the project as long as it was constructed above the 566-foot line of inundation. While these discussions advanced, the federal government continued acquiring all of the surrounding parcels subject to the new inundation limits while concurrently issuing a new set of flood plain maps reflecting the new lines of inundation. The City of Chino followed suit, and amended its zoning plans, limiting the land below the 566-foot elevation to agricultural purposes while concurrently prohibiting any residential and commercial development.

Following completion of the dam in February 2009, the government resumed its roughshod negotiations with Steuve and their neighbors, Mill Creek Farming Associates, eventually compelling the beleaguered property owners to file a federal lawsuit, alleging an inverse takings claim under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution. Steuve Bros. Farms sought $60 million in damages. The United States responded by filing a motion to dismiss, claiming that there was no valid “physical takings claim,” arguing that because there had been no flooding, there had been no “physical invasion” of the property, essentially mooting the takings claim. Much to the chagrin of Steuve, the court agreed and dismissed the complaint on July 3, 2012. In the course of the legal proceedings, the Steuve Brothers learned about the monuments. As soon as they did, they hired civil engineer Robert Beers, to review the 1992 Kapp survey and to unearth and photograph the six buried monuments, now that they had been made aware of the hidden monuments. Beers, in turn, hired Hunsaker and Associates, a local land surveying firm, to assist him. Supervising Land Surveyor Alan C. Hillwig, performed the actual field work and in a sworn affidavit submitted to the court, in support of Steuve and Mill Creek, Hillwig stated “Upon excavating the disks and inspecting them, I have determined that these disks are 3 and 5/8ths inches in diameter and were inserted under the ground in a manner which would not make them visible by observation from the surface.”

Relying on Hillwig’s declaration, Steuve and Mill Creek’s filed a motion for reconsideration and the court granted it, in part and denied it, in part. Steuve filed a Notice of Appeal from that portion of the court’s judgment and opinions, dismissing the complaint, holding that the federal government had not taken a flowage easement between the 556-foot and 566-foot lines of inundation. Following another round of arguments, the court issued another ruling, declaring that the language of the easement, in and of itself, does not and cannot create a flowage easement ruling that an easement can only be created by actual flooding. In an unexpected turn of events, the court ruled that the only portion of the land subject to the inverse claim was the area occupied by the six survey monuments, while concurrently excluding the alleged $60,000,000 in damages to the balance of the Property. The court did though find that Steuve’s arguments concerning the government’s delay in acquiring the property could be considered a violation of due process because of the delay following the government’s release of the original 566-foot flood inundation map 24 years earlier. Steuve argued that the delay “froze” their development plans for twentythree years and violated Steuve’s right to due process under the Constitution.

Relying on Hillwig’s declaration, Steuve and Mill Creek’s filed a motion for reconsideration and the court granted it, in part and denied it, in part. Steuve filed a Notice of Appeal from that portion of the court’s judgment and opinions, dismissing the complaint, holding that the federal government had not taken a flowage easement between the 556-foot and 566-foot lines of inundation. Following another round of arguments, the court issued another ruling, declaring that the language of the easement, in and of itself, does not and cannot create a flowage easement ruling that an easement can only be created by actual flooding. In an unexpected turn of events, the court ruled that the only portion of the land subject to the inverse claim was the area occupied by the six survey monuments, while concurrently excluding the alleged $60,000,000 in damages to the balance of the Property. The court did though find that Steuve’s arguments concerning the government’s delay in acquiring the property could be considered a violation of due process because of the delay following the government’s release of the original 566-foot flood inundation map 24 years earlier. Steuve argued that the delay “froze” their development plans for twentythree years and violated Steuve’s right to due process under the Constitution.

The court dismissed that claim because Steuve had not raised those arguments earlier. With regards to the 24-year old inundation map, the court acknowledged that an “official map” or “map of reservation” is a powerful tool to preserve land that is needed to build or widen planned or existing transportation corridors or to expand flowage or other open space easements, adding that “the apprehension of future flooding” may influence property value, zoning decisions, and flood plain maps, such apprehension is insufficient to establish a taking. Lastly, given the nominal value of the land occupied by the six survey monuments (an area no larger than a phone book), Steuve did not seek compensation for the de minimis loss of land. They remain buried, two-feet below grade, once again, invisible.

Note: A PDF of this case, Steuve Brothers Farms, LLC v. United States 737 F.3d 750 (Fed. Cir. 2013) can be found at http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-federal-circuit/1652055.html