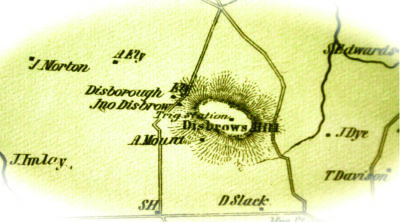

Triangulation Station Disboro is on a prominent “high” point (elevation 276) on this 1851 map of Monmouth County, NJ based on surveys by Jesse Lightfoot.

John O’Brien is a well-known illustrator and cartoonist, notably for The New Yorker. In 1995, he created a cartoon of four hikers roped together walking over flat terrain, or at most an extremely mild hill, with the caption, “The South Jersey climbing team attempts to climb Mount Laurel after successfully scaling both Mount Holly and Mount Ephraim.” For the uninitiated, these are names of towns in Burlington County, New Jersey, about two thirds down the western side of the state where, admittedly, even two-foot contours are generally fairly widely spaced.

For some, O’Brien’s joke might be taken as an insult, but for New Jersey’s State Geologist Jeff Hoffman it was the inspiration to write a report (just published in 2017 as Technical Memorandum 17-1) entitled “Highest Elevations by County in New Jersey.” As a surveyor, of course I had to look. Well, I can now tell you that Denali (the highest peak in North America at 20,310 feet above sea level according to 2015 GPS observations) has no challengers here.

Hoffman’s study utilized the latest statewide 10-foot digital elevation model and Arc GIS, so there may be some margin of error here, but not too significant. Of New Jersey’s 21 counties, he found that 12 have high points below 500 feet, another three range between 500 and 900 feet, and just five rise above 1000 feet, with the highest point in the state located in High Point State Park, boasting a whopping 1803 feet. Five of these “highest points” are on landfills, which is the case for the lowest high point in the state, down south in Cape May County. The landfill’s high point there is at 149, while the highest natural point is only 62.

Aside from obsession with what non-surveyors may consider trivia, investigating high points and how they have changed over time reveals how, and sometimes why, our topography has changed over time. In the instance of landfills being the highest point of the studied areas, this illustrates the effect of human actions on the landscape. As a result, sometimes high points don’t need to be impressively tall to be important. Those of our colleagues who have been involved in archaeological excavations understand this significance.

More than just finding cool antique bottles, the strata of human discards amid accumulations of soil and rocks chronicle how people lived and how long they inhabited a particular area. The site of Tel Beit She’an in northern Israel is a particularly interesting example, with excavations into the mound (Tel) that rises about 260 feet above the still populated ancient city (where the elevation is approximately 400 feet), revealing at least 18 levels of occupation estimated as dating back to 8000-6000 BCE. A massive earthquake in 749 CE toppled and buried many of the uppermost buildings, encapsulating some in the earth and rubble until excavation in the 1920s and 1930s began to bring them to light. When I visited in 2014, there was discussion about what to do about the discovery of a city beneath the then exposed and marvelous Roman development. The highest point here was hiding much older history; should the decision be made to destroy one city to study an older one below?

For surveyors, high points have traditionally provided the best observation points for our work, and this was central to the first triangulation system created by our first Superintendent of the first U.S. Coastal Survey, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler. Not long after the United States became an independent nation, the problem of too many shipwrecks along the eastern coast was traced to the lack of good mapping. We also needed maps to be able to defend our shorelines from other nations, particularly Great Britain. Hassler established a network of 18 stations from Philadelphia to New York, choosing points that could be visible from great distances.

As might be suspected from the 2017 report on New Jersey’s highest points, none in that state were impressively high, and the triangulation stations themselves were not necessarily at the highest points in the counties where they were set. In 1982, I was part of a group of New Jersey surveyors looking for (and finding) the then long-unseen marker in Millstone Township, Monmouth County on Disbrow’s Hill (the station itself known as Disboro). This 1839 marker was hidden from sight under a tangle of forest and briars, and at an elevation reported to Congress as being 268 feet it was not even the highest point in the county, which Hoffman’s study reports as currently being 374 feet. But with the help of lime fires at night, the long lines could be surveyed accurately, forming the basis of a system that has since been expanded well beyond the original compact system.

Height and elevation do matter, but it isn’t always the record holders that are most important.

For More…

See the cartoon that started it all: https://goo.gl/whgRTk

Hear the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection podcast interviewing both O’Brien and Hoffman talking about humor and topography at: Episode 70–High Points in New Jersey with John O’Brien and Jeff Hoffman https://goo.gl/cMQatJ

For those who live in high places who might be amused, Technical Memorandum 17-1 describing New Jersey’s highest points is available free on line: https://goo.gl/gFGZhS

For the map of Hassler’s triangulation system through New Jersey in NOAA’s Historical Map & Chart Collection: https://goo.gl/SbmK8S